How do we process unimaginable betrayal? How do we overcome

the kind of events that forever alter the trajectory of a life we so

desperately want back? These are just two of the questions addressed by

Christian Petzold’s masterful “Phoenix,” a film that firmly cements its

director as one of the most impressive working today. With echoes of “Vertigo,”

and a deeply confident visual language, Petzold’s film resonates long after its

perfect ending. This is a riveting piece of work that never loses sight of its

human story while also serving as a commentary for how an entire country deals

with tragedies like war. A film this satisfying on every level—one that can be

enjoyed purely for its narrative while also providing material for hours of

discussion on its themes—is truly rare.

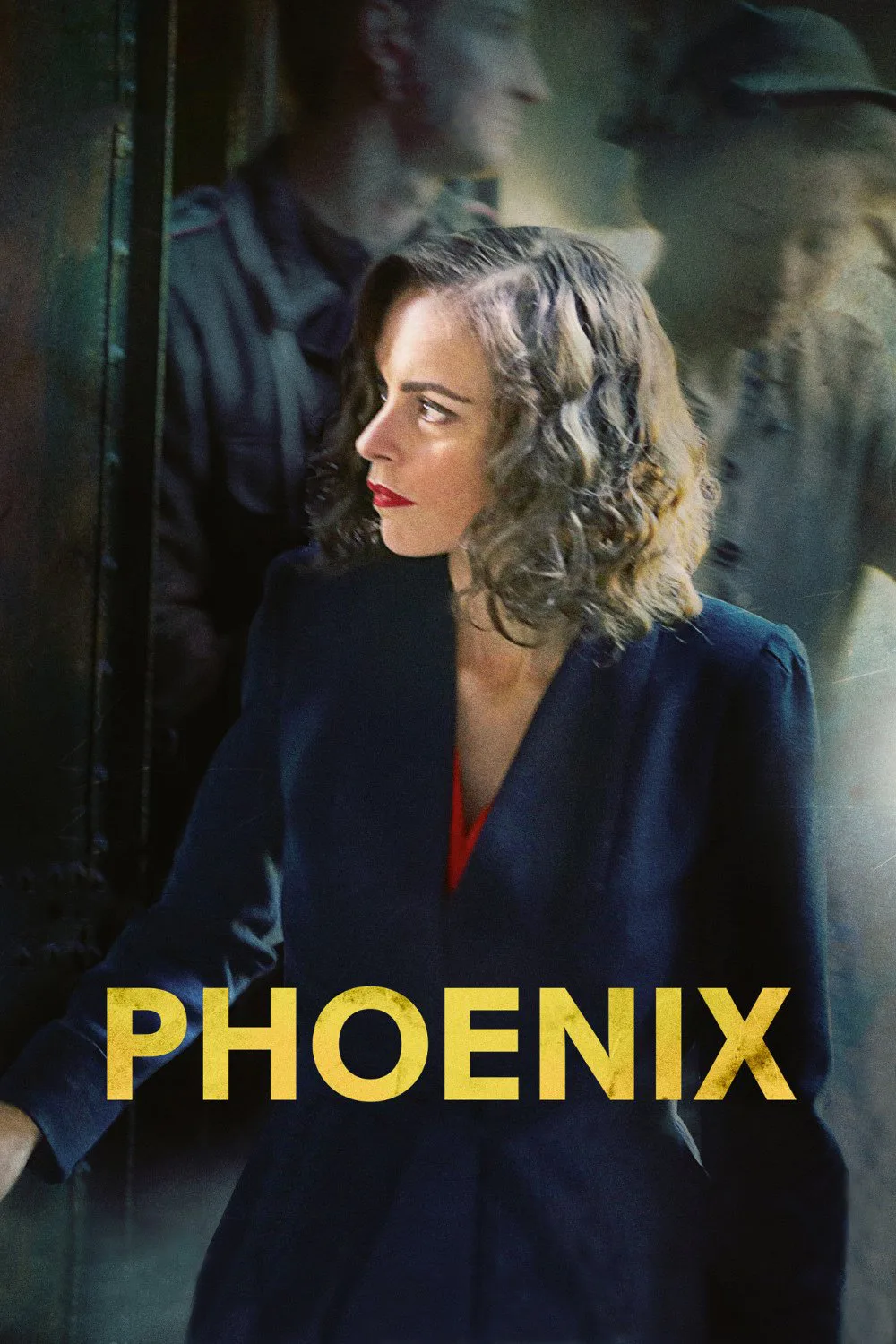

“Phoenix” opens with a face profiled in darkness. It is the

face of Lene (Nina Kunzendorf), a woman driving a bandaged and bloodied

passenger back to Berlin. Her face has been badly damaged, but she is a

survivor of a concentration camp. After a brief encounter at a checkpoint, the

pair drives further and headlights fill the screen before the title comes up.

This story will clearly be one of darkness to light, even if it’s a light that

sometimes blinds you.

We learn that the passenger is Nelly Lenz (Petzold’s

collaborator, Nina Hoss), a German-Jewish nightclub singer, who, from the

appearance of photographs and discussions with friend Lene, had a happy life. She

was married to a handsome, confident man named Johnny (another Petzold regular,

Ronald Zehrfeld). On October 4th, Johnny was taken in for

questioning by the SS. Two days later, he was released, and Nelly was

transported to a concentration camp. Did Johnny betray his wife’s Jewish

background? Clearly. And yet Nelly refuses to believe it. She wants her old

life back. And that means denial that her husband was and is a self-serving

monster. After her plastic surgeon advises her that she can look like anyone

and start a new life, she tells him, “I

want to look exactly like I used to.” She is defiantly, stubbornly in denial

about what has happened to her.

Over Lene’s objections, Nelly returns to Berlin, seeking out

Johnny. She is a shattered woman in a city of rubble. She tells Lene, “I no longer exist.” The relationship,

the friends she now sees only in pictures, even the city she once lived in—they’re

all gone. She finds some semblance of familiarity in Phoenix, the nightclub

that literally looks like an oasis in ruins. It’s like a dream that people find

amidst the rubble of a bombed-out city. And that’s where she finds Johnny. He

grabs her one night. He has a plan. He needs someone to pretend to be his dead

wife, so he can claim her inheritance as there’s no evidence that his wife is

dead. “You have to play my wife.” And

the parallels between “Phoenix” and “Vertigo” come into strong focus as Johnny

begins to turn this woman he believes is a stranger into the wife he betrayed,

and, in doing so, brings Nelly back to life.

Every choice in “Phoenix” has been carefully considered and

yet never in a way that it smothers the realism of the piece. It’s a film that has a deep cinematic language that avoids calling attention to its

style. Petzold’s choices are subtle, from the way he frames the expressive

faces of his actors to the choice of “Night and Day” in a crucial club scene to a climactic conversation that takes place on a train track, so deeply symbolic of looking in one direction to the past and the other to the future (as well as carrying historical weight with the trains that took people like Nelly to concentration camps).

Dark and light, rising from the ashes, the overhead lighting or neon red of the

Phoenix sign—Petzold plays so subtly with visual expression of his themes that

he doesn’t draw attention to them, just allows them to be the background to his

human drama.

And that human drama is where Nina Hoss takes center stage.

Watch the scene in which she takes off her hat in a club after seeing Johnny

walk by for the first time. She calls his name, happily, even though she knows

what he’s done. It’s a name she’s called so many times before. He looks past

her. Or maybe he looks at her and doesn’t see her. She can’t be there. His

brain can’t even recognize the possibility that she would be. Hoss puts her

hand to her mouth in horror. It’s not Johnny’s betrayal but Johnny’s dismissal

that hurts her now. This walking embodiment of when things made sense can’t see

her anymore, and so when he gives her the chance to “become Nelly” again, she

takes it. At one point, Johnny asks Nelly to help craft a story about what he

believes is her false narrative of her time in a concentration camp. Of course,

the story Nelly starts to tell is true. Hoss holds her hands to her face, shaky,

unable to speak fluidly. And Johnny is equally uncomfortable. The fiction he

believes he’s creating and the reality they’re both denying are starting to

intersect. Hoss is simply amazing in this scene, and really throughout the film.

To be fair, Zehrfeld is very good as well. Watch a moment in

which he comes home to find Nelly in the right dress, made-up, and looking more

like Nelly of the past. Is that a moment of recognition on his face? Awareness

of what he’s done? No, it can’t be. He can’t be that person and she can’t be

alive. She’s a ghost, a reminder of what he’s done and what the entire world lost in WWII.

If we’re lucky, a few times a year we get as complete a package as “Phoenix.”

We get character studies with performances as strong as Hoss and Zehrfeld are

here every now and then, or we get auteur-driven films with complex visual choices and an emphasis on

style. It’s uncommon to see a film so balanced that it serves as a commentary

on the human need to deny war and betrayal while never losing sight of the

story of a pianist and nightclub singer in 1945 Berlin. “Phoenix” works on so many levels, it’s the kind of piece that can be dissected and appreciated for decades. And I expect it will be.