I always wanted to be a photographer for National Geographic, but it wasn’t until I was in college that I learned about visual anthropology. Anthropology taught me about foreign histories and cultures, but I also learned about myself and the world around me through filmmaking. As the 21st century advances, media literacy becomes just as important as agriculture and natural resources. We need to understand the media we watch and better understand how to produce it and control it to tell our own stories. And visual anthropology gives us insight into these very things.

Visual anthropology is a field under the umbrella of cultural anthropology. It includes ethnography, a detailed written analysis based on observation and participation in fieldwork; documentation, which uses photography, video, and audio to observe and record fieldwork research and practices; and exhibition or sensory media production, which creates and analyzes visual and physical representations of one’s fieldwork. Anthropologists often show visual representations of their fieldwork in galleries, museums, educational institutes, public artworks, and, of course, films.

Visual anthropology and documentary fields grew together as technology and travel became more accessible. Not all anthropologists make documentary films, and documenting people, places, and events can be expressed in various ways. Not all documentaries result from anthropological research, but many of the techniques documentary filmmakers employ today are grounded in traditional ethnographic fieldwork methods.

For instance, observational cinema. One of the most popular anthropologists of the time, Margaret Mead, was known for placing her camera on a tripod and filming over a period of time in hopes of capturing her subjects in their natural routines. While documentary filmmakers of today are not likely to just leave a camera on a tripod for hours, we do see the approach of observing scenes without questions or comments from the director, allowing the action to unfold in real-time in such award-winning documentaries as “20 Days in Mariupol” or “All That Breathes.”

Anthropologists experimented a lot with the form of documentary in the early years, even taking the language of fiction filmmaking and applying ideas like shots, characters, and plot into their documentaries. Robert Flaherty is infamous for his film “Nanook of the North,” which plays with the idea of documenting real life by constructing the scenes themself. Flaherty constructed an igloo and cut it in half to film Nanook and his family as if they lived there. Anthropologists and documentary filmmakers continue to struggle with the ideas of reality vs fiction and authenticity vs. representation.

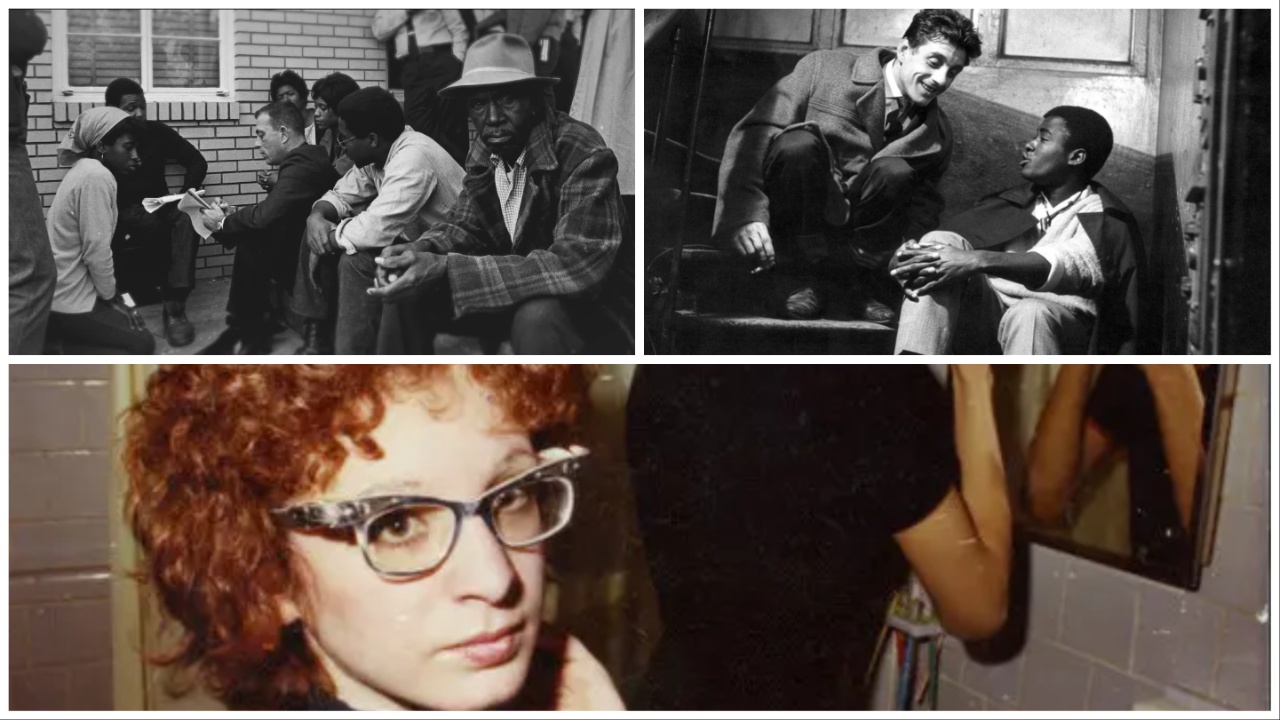

During the French New Wave of filmmaking, another approach arose that sought to capture real life as it was happening. Cinema Verite not only wanted to observe the subjects but also wanted to be in the scene with the subjects. Ideas of reflectivity and participant observation are explored most notably in the film “Chronique D’Un Été” by Jean Rouch. In this groundbreaking documentary, we see subjects speaking to themselves, to each other, directly to the director, and all of them ultimately grappling with the images of themselves on screen. Before this, subjects rarely spoke and certainly not as any authority on their lives. The voice-over of God was very common in documentaries, explaining what was happening in the footage. Even now, filmmakers question the influence of the camera and themselves on their subjects. Directors often look for ways to obscure the camera to get the most authentic moments between subjects and the director, and our subjects mostly speak for themselves now. I modeled my own short documentary, “Chronicles of the Summer,” about life for 8-year-old girls in south Chicago after the Rouch film to show how children can speak about their own lives and cultures.

Learning about visual anthropology was like discovering I belonged to an ancient, long-lost tribe. I came into anthropology and documentary at a time when it felt like all the world’s cultures had been discovered and there wouldn’t be anywhere new to go. I began learning more about post-modern fieldwork in urban areas and sub-cultures being created now. While I enjoyed learning about exotic places, I wanted to capture the culture, people, and events happening right around me. This made visual anthropology a perfect fit for me.

I chose anthropology because I wanted to learn about others, but making documentaries has taught me much more about my own culture and history. Many of my short films are about women, mothers, children, and young girls whose lives are similar to mine. I make films to call people to action regarding women’s rights, education, and more. As a Black person, I am passionate about the social-political history of America and the diaspora. At Participant, I had the privilege to work with seasoned professionals like Melissa Robledo, Sam Pollard, and Laura Poitras on feature documentaries about historic and political issues impacting society today. “Food Inc 2,” “Lowndes County and The Road to Black Power,” and the Oscar-nominated “All the Beauty and The Bloodshed” were not just archival/verite documentaries but films created to impact their audiences and encourage societal change.

I feel responsible for fostering the development of future documentary filmmakers and researchers, so I started Collected Voices Ethnographic Film Festival to highlight the films created by young people, anthropology professors, and professional filmmakers. I have worked with many producers over the years, and I wanted to give them a platform to screen and discuss their work beyond awards season. I worked with Community Filmworkshop and Reel Black Filmmakers to build an audience for ethnographic films from Chicago and worldwide.

I know some people enter the world of documentaries hoping to hit it big and get rich! But you might want to reconsider if that’s your goal. While it’s easy to look at the Hollywood landscape and feel like the industry is shrinking, I see more demand for emerging documentary filmmakers than ever. Hollywood budgets are bloated, have huge crews, and unpredictable schedules. But, the anthropological approach offers smaller production crews, limited schedules and budgets, and more authentic moments for a greater social impact. There are still opportunities in LA for passionate, dedicated filmmakers willing to give their all to produce their films.

It’s essential that media education begins in elementary and that more young people have the tools and resources available in their schools and youth centers to experiment with filmmaking. People now make entire films with their phones and constantly post narrative scenes on their IG. Knowing filmmaking allows us to challenge notions of who gets to record history and push the boundaries of storytelling with less expense. Sure, not everything is good, but I find amazing gems of ethnographic media every day online! I know that the power to film is in the hands of the masses more than ever before. So, what story are you documenting?

Ife Olatunji, MA, BA, is a visual anthropologist, documentary filmmaker, writer, and producer. They are the daughter of UCLA, LA Rebellion filmmaker Iverson White, and musical theatre actress & activist Una Vanduvall. Ife has researched in Brazil, Ghana, India, and more, producing photography and films through ethnographic observational fieldwork, and is currently an independent producer and film critic in Los Angeles, CA. Visit FreedomLoverFilms.com and LinkedIn for more information.