“Radical Wolfe,” Richard Dewey’s engaging documentary portrait of writer Tom Wolfe (“The Right Stuff,” “Bonfire of the Vanities”), derives from a 2015 Vanity Fair article by Michael Lewis. There’s no small irony in the fact that Lewis, the bestselling author of three books that were turned into Oscar-winning movies (“The Blind Side,” “Moneyball,” “The Big Short”), today is surely far better known than the writer he so reveres.

Affable on camera, Lewis appears throughout “Radical Wolfe,” and his presence gives the chronicle a warm, personal tone. Not only a well-qualified Wolfe expert by virtue of having been friends with the writer during Wolfe’s final years (he died in 2018 at age 88), Lewis also recalls how, as a kid, he pulled a Wolfe volume off his father’s shelf and was struck that the words he read seemed to explode off the page with a force of a singular personality: the author’s.

For readers too young to have been there, it’s worth noting that in the ‘60s, not only did film directors and rock stars become auteurs, celebrated for their individual styles and inimitable visions, but journalists did too. And if their influence is perhaps less well remembered today, it was splashy, profound, and lasting.

As Lewis puts it in his Vanity Fair piece: “In the late 1960s, a bunch of writers leapt into the void: George Plimpton, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson, and the rest. Wolfe shepherded them into an uneasy group and labeled them the New Journalists. The New Journalists —with Wolfe in the lead—changed the balance of power between the writers of fiction and the writers of nonfiction, and they did it chiefly due to their willingness to submerge themselves in their subjects and to steal from the novelist’s bag of tricks: scene-by-scene construction, use of dramatic dialogue, vivid characterization, shifting points of view, and so on.”

Born and raised in Richmond, Virginia, and educated at Washington and Lee University and Yale, Wolfe was an impecunious newspaperman in his early thirties when he pitched Esquire on an article about the new car culture among young people in southern California. The magazine’s largesse allowed him to spend plenty of time observing his subjects, but when he returned to New York, he hit the mother of all writer’s blocks. The magazine had commissioned an expensive photo layout for the piece, so Wolfe’s editor told him to write some notes, allowing another writer to provide text for the illustrations. Instead, he went home and furiously typed out a massive letter about his SoCal experiences to his editor, who, after receiving it, simply cut off the salutation and ran its several thousand words as Wolfe’s piece.

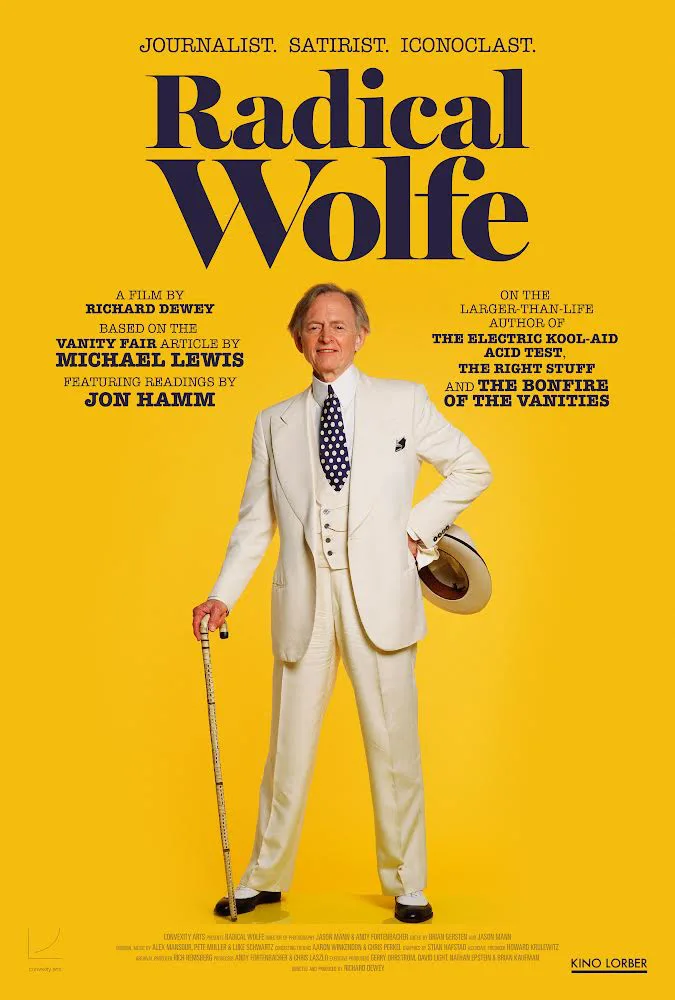

There Goes (Vroom! Vroom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby was its title, and it was a sensation, launching Wolfe as a celebrity and one of America’s most sought-after journalists. Like some of his counterparts, he adopted a public persona, his centered on tailored white suits and matching accessories such as hats and canes. In this get-up, with his baby face and lanky hair swept over one eye, Wolfe became a regular on talk shows and at Manhattan soirees. People wondered how someone so recognizable and famous could infiltrate closed societies and get people to relax and open up to him, but he did. He did it when invading the world of NASCAR to profile driver Junior Johnson, and he did it when joining the LSD-fueled odyssey of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters for The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, my favorite of Wolfe’s many books.

That work and others established his furiously eccentric style of breathless capitalizations, exclamation points, ellipses, and so on. But Wolfe wasn’t simply out to become a buzzy stylist. His literary forebears and ambitions pointed him toward being an irreverent, nervy, and increasingly ambitious social and cultural critic. Most famous in that regard was his 1970 piece, Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s, wherein Wolfe infiltrated a tony gathering at the apartment of Leonard Bernstein and his wife, which was staged to raise money for the Black Panthers. Wolfe’s gleeful, merciless ridiculing of the participants introduced “radical chic” into the national lexicon and deflated the trend of well-to-do liberals displaying their leftist credentials by holding fundraisers for radical groups. (In the documentary, someone remarks that this was the one time when Wolfe’s satire became personally cruel, and it is suggested that Bernstein and his family never got over it.)

As that famous article shows, Wolfe was not a radical himself. Rather, his outlook reflected his conservative Southern upbringing. Yet his conservatism was always idiosyncratic and personal; it never became doctrinaire or polemical, though it was arguably more and more evident when he turned from focusing on journalism to writing books, all of which became huge bestsellers. The first of these, The Right Stuff, his last work of nonfiction, profiled the Mercury astronauts as a group of carefully managed conformists lacking the heroic edge that Americans ascribed to them during the race to the moon.

Speaking personally, I found this book’s thesis – which was turned into a hyperbolic, overrated movie – facile and unpersuasive. My waning regard for Wolfe’s work continued with his first work of fiction, The Bonfire of the Vanities, which admittedly captured the go-go capitalistic frenzy of New York in the ‘80s with great wit and pungency but was also full of stereotypical characters and situations. (Yet it was inarguably far superior to the disaster of a movie that Brian De Palma made of it.) Wolfe’s next novel, A Man in Full, was also a huge success, yet the ones that followed, I Am Charlotte Simmons and Back to Blood, seemed to prove the law of diminishing returns. Nevertheless, Wolfe kept working on the massive tomes and enjoying renown as a literary elder statesman.

Dewey’s film features many interviewees who comment on his work, both appreciatively and critically, but the tone that dominates is Lewis’ fond approbation. And if there’s a note of reflexive nostalgia in the proceedings, that inevitably has to do not just with the man at the film’s center but with the era that produced him, a time when magazine and print journalism could take writers and make instant celebrities and hugely influential cultural figures out of them. That day is long gone, but “Radical Wolfe” makes a strong case that it’s well worth remembering.

Now playing in select theaters.