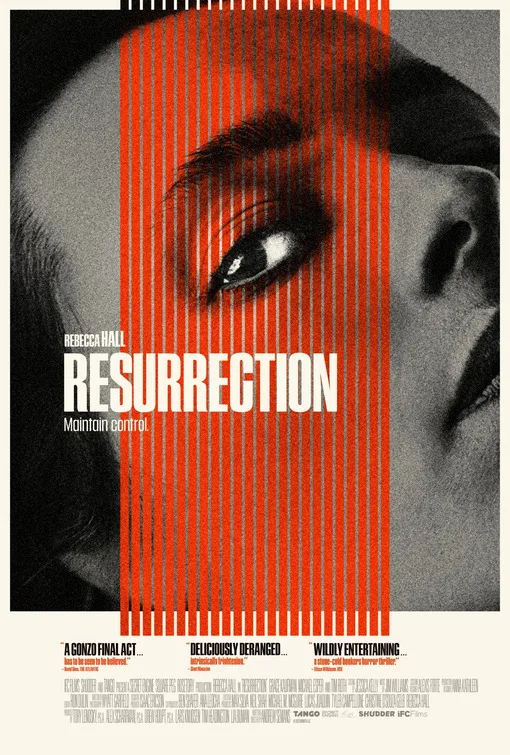

“Resurrection” starts with a cold open: a young woman (Angela Wong Carbone) sits in a glassy modern office, sharing her man-problems to someone off-screen. Her “confessor,” Margaret (Rebecca Hall), is first seen sitting on the side of her desk, her lean body twisted around itself, her neck elongated and exposed in a disturbingly vulnerable and yet somehow aggressive way. Is Margaret an HR representative? Is she this young woman’s mentor? The cold open leaves a strange impression. Margaret refers to the young woman’s boyfriend as a “sadist,” an exaggerated word choice. Her delivery is off-putting. Margaret, in general, is off-putting. Written and directed by Andrew Semans, “Resurrection” is a diabolically intense psychological thriller, with two riveting central performances from Hall and Tim Roth, neither of whom shy away from the dark nutty territory they are required to enter.

Margaret has a high-powered job in the biotech industry, where she presents Power Point documents on replacement therapy and “cell membrane re-organizing,” a metaphorical career if ever there was one. Everything Margaret does, she does intensely. To say Margaret is an over-protective mother of her 17-year-old daughter Abbie (Grace Kaufman) is to completely understate the situation: Margaret hovers, worries, clings, and Abbie, about to leave for college, feels suffocated. Margaret has a friends-with-benefits situation (sans the “friends” part) with a married co-worker (Michael Esper), and takes a daily run that looks more like a military maneuver than requisite exercise. She runs like she’s chasing someone, she runs like she’s trying to beat the clock. Jim Williams’ urgent score, all chopping alarmist strings, makes every moment into an incipient life-or-death catastrophe, and for Margaret, it is.

At a conference, Margaret gets a side glimpse of a man in attendance. This, we find out, is David (Tim Roth), whom she hasn’t seen in two decades. The film gives no backstory before David arrives (although the clues are there in Margaret’s hyper-vigilant personality), and so all we see is Margaret suddenly fleeing the conference, in a total fight-or-flight panic. She runs all the way home and hides in the bathroom, crooking her elbow over her mouth to muffle her sobs. Eventually, Margaret provides the details in a seven-minute monologue to the hapless young co-worker seen in the cold open. The details are gnarly, to say the least. The relationship between David and the teenage Margaret was bad, sure, but it was bad in a sinister way, something far far out there at the limits of human experience. The word “sadist” may not have applied to the young co-worker’s boyfriend, but it applies to David. (The monologue, and Hall’s performance of it, called to mind Bibi Andersson’s similar monologue about the boys on the beach in “Persona,” not in the particulars, but in its personality-destabilizing revelations. Margaret has never told the story out loud before.)

Margaret fled David soon after they got together, but the damage was more than done. She’s been on the run ever since. Everywhere she goes now, she sees him. She confronts him. It seems, at first, he doesn’t know who she is. But he then cracks a huge smile at her, the smile of a true maniac, and you can see the nastiness underneath, the nastiness tying them together. She tries to file a police report. But there’s nothing to report. He was at a conference, he was sitting in a park. There’s no crime. Margaret doubles-down on her vigilance over Abbie, and begins a stalking campaign. She follows David around, keeping tabs on him. She loses sleep. At one point, after a frightening close-call, she comes home, only to find her breasts have leaked milk through her shirt. Something is happening to her. It’s all out of her control.

Any expectations you may have going in about how this all will end—a woman gets revenge on the “toxic” man who “groomed” and then abused her—will be dashed on the rocks. There are many stories like that. “Resurrection” is not one of them. The whole thing doesn’t entirely fit together, and the final scenes move into something almost supernatural, definitely hallucinatory, where Margaret’s version of events can no longer be trusted (and maybe they were never to be trusted to begin with). Is Margaret a reliable narrator? I’m not sure that that matters. The film stays in her point-of-view, and so we have to take her word for it. Her sense of threat is real, and Roth’s soft-voiced reasonable menace is so hair-raising you want her to run in the other direction. But something still ties them together. She is drawn into his deranged orbit, against her will, where he sets the rules, and creates the reality in which she lives. He says at one point, “I’m the only person that can see you. Who knows who you really are.” The worst part about this terrifying sentence is that it’s true.

Rebecca Hall goes deeper than most other actors go. Her reactions are never “stock.” There’s not a cliched bone in her body. She’s unafraid of contradictions, flaws, the dark side, the unknowability at the heart of so much of life. She understands debilitating depression, irrationality. She seems to not care about being “liked.” This is very much in her favor and shows in her intuitive choice of roles. “Resurrection” is not a pleasant watch (and it could use some humor to lighten the load), but Hall is the essence of unmanaged trauma and rampaging guilt, guilt she’s refused to feel for 20 years. She can no longer stop herself from feeling all these things, and it destroys her. In films like “The Gift,” “Christine,” and last year’s “The Night House,” Hall gives extremely heavy-hitting performances, vibrating with real feeling and understanding. And Tim Roth, always fascinating to watch, outdoes himself here. He doesn’t have to raise his voice to seem threatening or scary. In fact, it’s his intimate almost kind tone—like he alone knows what she needs to move past the trauma—that makes it such an incredibly frightening performance.

Margaret and David go into the final section tightly bonded together as characters, adversarial and yet connected in queasy-making ways. I’ve read some reviews where critics express surprise about where the film ultimately goes, its bonkers ending, but the nightmare-scape of the emotions on display—and the dynamic between the characters—lays the groundwork pretty clearly. “Resurrection” is not sane territory. There’s something a little over-determined about all of it, a little over-planned and micro-managed (belied by the visceral reality of the performances). 2020’s “The Swerve” trod on similar ground—a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, and then over the damn edge—but with much more effectiveness and control. Still, Hall and Roth together is a pleasure, and “Resurrection” is so crazy you don’t know what will happen, right up until the moment the screen goes black for the end credits. I appreciate wildness like this, wildness that takes risks and refuses to comfort or console.

In theaters tomorrow, July 29th.