The soldiers assigned to find Pvt. Ryan and bring him home can do the math for themselves. The Army Chief of Staff has ordered them on the mission for propaganda purposes: Ryan’s return will boost morale on the homefront, and put a human face on the carnage at Omaha Beach. His mother, who has already lost three sons in the war, will not have to add another telegram to her collection. But the eight men on the mission also have parents–and besides, they’ve been trained to kill Germans, not to risk their lives for publicity stunts. “This Ryan better be worth it,” one of the men grumbles.

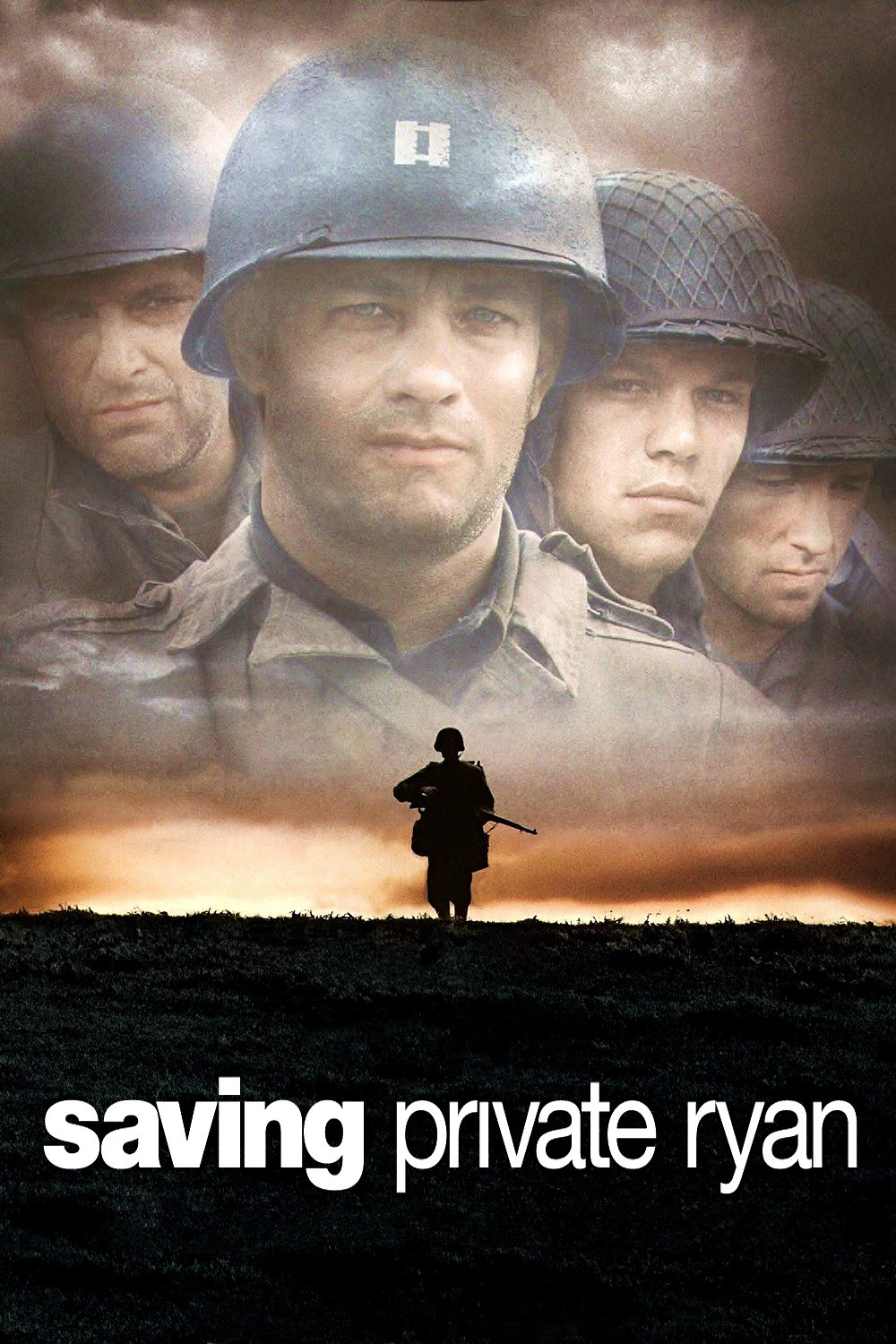

In Hollywood mythology, great battles wheel and turn on the actions of individual heroes. In Steven Spielberg‘s “Saving Private Ryan,” thousands of terrified and seasick men, most of them new to combat, are thrown into the face of withering German fire. The landing on Omaha Beach was not about saving Pvt. Ryan. It was about saving your skin.

The movie’s opening sequence is as graphic as any war footage I’ve ever seen. In fierce dread and energy it’s on a par with Oliver Stone’s “Platoon,” and in scope surpasses it–because in the bloody early stages the landing forces and the enemy never meet eye to eye, but are simply faceless masses of men who have been ordered to shoot at one another until one side is destroyed.

Spielberg’s camera makes no sense of the action. That is the purpose of his style. For the individual soldier on the beach, the landing was a chaos of noise, mud, blood, vomit and death. The scene is filled with countless unrelated pieces of time, as when a soldier has his arm blown off. He staggers, confused, standing exposed to further fire, not sure what to do next, and then he bends over and picks up his arm, as if he will need it later.

This landing sequence is necessary to establish the distance between those who give the order that Pvt. Ryan be saved, and those who are ordered to do the saving. For Capt. Miller (Tom Hanks) and his men, the landing at Omaha has been a crucible of fire. For Army Chief George C. Marshall (Harve Presnell) in his Washington office, war seems more remote and statesmanlike; he treasures a letter Abraham Lincoln wrote consoling Mrs. Bixby of Boston, about her sons who died in the Civil War. His advisors question the wisdom and indeed the possibility of a mission to save Ryan, but he barks, “If the boy’s alive we are gonna send somebody to find him–and we are gonna get him the hell out of there.” That sets up the second act of the film, in which Miller and his men penetrate into French terrain still actively disputed by the Germans, while harboring mutinous thoughts about the wisdom of the mission. All of Miller’s men have served with him before–except for Cpl. Upham (Jeremy Davies), the translator, who speaks excellent German and French but has never fired a rifle in anger and is terrified almost to the point of incontinence. I identified with Upham, and I suspect many honest viewers will agree with me: The war was fought by civilians just like him, whose lives had not prepared them for the reality of battle.

The turning point in the film comes, I think, when the squadron happens upon a German machinegun nest protecting a radar installation. It would be possible to go around it and avoid a confrontation. Indeed, that would be following orders. But they decide to attack the emplacement, and that is a form of protest: At risk to their lives, they are doing what they came to France to do, instead of what the top brass wants them to do.

Everything points to the third act, when Private Ryan is found, and the soldiers decide what to do next. Spielberg and his screenwriter, Robert Rodat, have done a subtle and rather beautiful thing: They have made a philosophical film about war almost entirely in terms of action. “Saving Private Ryan” says things about war that are as complex and difficult as any essayist could possibly express, and does it with broad, strong images, with violence, with profanity, with action, with camaraderie. It is possible to express even the most thoughtful ideas in the simplest words and actions, and that’s what Spielberg does. The film is doubly effective, because he communicates his ideas in feelings, not words. I was reminded of “All Quiet on the Western Front.” Steven Spielberg is as technically proficient as any filmmaker alive, and because of his great success, he has access to every resource he requires. Both of those facts are important to the impact of “Saving Private Ryan.” He knows how to convey his feelings about men in combat, and he has the tools, the money and the collaborators to make it possible.

His cinematographer, Janusz Kaminski, who also shot “Schindler's List,” brings a newsreel feel to a lot of the footage, but that’s relatively easy compared to his most important achievement, which is to make everything visually intelligible. After the deliberate chaos of the landing scenes, Kaminski handles the attack on the machinegun nest, and a prolonged sequence involving the defense of a bridge, in a way that keeps us oriented. It’s not just men shooting at one another. We understand the plan of the action, the ebb and flow, the improvisation, the relative positions of the soldiers.

Then there is the human element. Hanks is a good choice as Capt. Miller, an English teacher who has survived experiences so unspeakable that he wonders if his wife will even recognize him. His hands tremble, he is on the brink of breakdown, but he does his best because that is his duty. All of the actors playing the men under him are effective, partly because Spielberg resists the temptation to make them zany “characters” in the tradition of World War II movies, and makes them deliberately ordinary. Matt Damon, as Pvt. Ryan, exudes a different energy, because he has not been through the landing at Omaha Beach; as a paratrooper, he landed inland, and although he has seen action he has not gazed into the inferno.

They are all strong presences, but for me the key performance in the movie is by Jeremy Davies, as the frightened little interpreter. He is our entry into the reality because he sees it clearly as a vast system designed to humiliate and destroy him. And so it is. His survival depends on his doing the very best he can, yes, but even more on chance. Eventually he arrives at his personal turning point, and his action writes the closing words of Spielberg’s unspoken philosophical argument.

“Saving Private Ryan” is a powerful experience. I’m sure a lot of people will weep during it. Spielberg knows how to make audiences weep better than any director since Chaplin in “City Lights.” But weeping is an incomplete response, letting the audience off the hook. This film embodies ideas. After the immediate experience begins to fade, the implications remain and grow.