Some people become actors because they crave an audience, a camera, a director, or the fans. Some do it because they love to become other people, transform themselves, or tell stories. Shelley Duvall, who died this week at age 75, became an actress because Robert Altman saw her and knew that movie-goers would be instantly drawn to her face, her slender, long-limbed body, and those big, wide eyes. She was a 20-year-old junior college student in her home state of Texas when Altman’s staff saw her at a party and asked her to bring the paintings by her boyfriend she was trying to help him sell to meet with some “patrons of the arts.” She brought 35 artworks to the meeting and explained each one. When she finished, they asked if she would like to be in a movie.

Altman cast her as Astrodome tour guide Suzanne in “Brewster McCloud,” and her pitch about the art became a part of her character’s dialogue. Duvall and Altman continued to work together, including two of his best films, “Nashville” and “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” one of his most intriguingly confounding, “3 Women,” and one of his biggest box office failures, “Popeye.” Perhaps it was her resemblance to the title character’s leading lady, Olive Oyl, that inspired him to make the film. Duvall said that while some people “intellectualize” about the characters they play, Altman told her to “relax, and you will fall into the role.” He encouraged her to develop her own dialogue for her characters. Duvall said that it wasn’t until her third film with Altman, “Thieves Like Us,” was shown at the Cannes Film Festival that she realized she wanted a career as an actor.

Duvall also had iconic roles in Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” as the Rolling Stone reporter who said sex with Allen’s character was Kafka-esque and that a rock concert was “transplendent,” and Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” as the wife of a man being consumed by homicidal madness.

She had a beguiling innocence and naturalism that could contrast with her exaggerated, easily caricatured, appearance. Duvall was not the kind of actress who transformed herself for a role. She made little effort to adopt a different accent or tone of voice, even when playing characters from other countries and centuries. Her interviews, her appearances as herself in the television series she produced, and her performances are seamless. That does not mean she was always herself on screen. It means that she was completely comfortable on screen, finding within herself whatever the character needed. In “3 Women,” for example, based on a dream Altman had, Duvall won the Best Actress award at Cannes for playing Millie, with an impeccably smooth pageboy haircut. Her character babbled on in a manner she intends to come across as confident and sophisticated, but we can see as insecurity and nervousness, while in “Annie Hall,” her journalist character has a lot of confidence, unearned but unquenchable. Both characters are completely believable. Altman said she “was able to swing all sides of the pendulum: charming, silly, sophisticated, pathetic, even beautiful.”

Duvall’s fearlessness made her a match for some of the screen’s most powerful co-stars. Not many performers can appear with Jack Nicholson at his most deranged and Robin Williams at his most cartoonish. She was more than able to hold the audience’s attention. Her Olive Oyl matched Williams’ stylized tone, but she was endearing, with her simple, heartfelt song “He Needs Me.” Duvall is completely natural as a devoted mother acting with then-six-year-old Danny Lloyd in “The Shining.” But there is no image in Hollywood history more iconic than her terrified face as Nicholson uses an ax to smash through the door. She had an exceptional ability, especially for someone so distinctive, to adapt to a stunning range of genres, tones, and co-stars. She acted opposite Monty Python’s Michael Palin in “Time Bandits,” Steve Martin in “Roxanne,” and Sissy Spacek in “3 Women.”

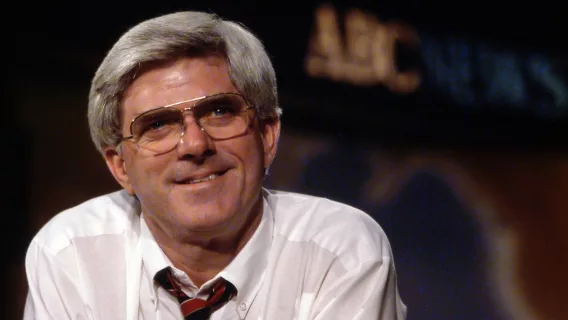

Roger Ebert wrote about a charming interview with Duvall.

Shelley Duvall is like a precious piece of china. She looks and sounds like almost nobody else, and if it is true that she was born to play the character Olive Oyl (and does so in Altman’s new musical “Popeye“), it is also true that she has possibly played more really different kinds of characters than almost any other young actress of the 1970s. In all of her roles, there is an openness about her, as if somehow nothing has come between her open face and our eyes — no camera, dialogue, makeup, method of acting — and she is just spontaneously being the character. You sense that as much in “3 Women,” where she flirts with men who ignore her, as in “Thieves Like Us,” where she smokes a cigarette like nobody else, or in “Nashville,” where she’s a goofy groupie, or in “Popeye,” where she wrestles with an octopus.

If Duvall had not been a movie star, she would still be remembered as the creator of beloved 1980s television series for families. Her Peabody Award winning “Faerie Tale Theatre,” followed by “Bedtime Stories” and “Tall Tales & Legends,” had witty scripts, brilliant actors, and fabulous costume and set designs. The fairy tale settings were inspired by the great illustrators like Maxfield Parrish, Norman Rockwell, Arthur Rackham, and Edmund Dulac. The dream casting included Robin Williams as the Frog Prince, Gena Rowlands as a witch, Christopher Reeve and Matthew Broderick as dashing princes, Carol Kane and Jean Stapleton as fairies, Liza Minnelli and Bernadette Peters as princesses, Paul Reubens as Pinocchio and Carl Reiner as Geppetto, and Elizabeth McGovern as Snow White. Duvall introduced each episode and appeared as Rapunzel.

In her later years, Duvall struggled with physical and mental health challenges, and appeared disoriented and frail on an episode of the Dr. Phil show. But last year, she appeared in the indie horror film “The Forest Hills” as the main character’s mother and the voice in his head. She had a long-term romantic relationship with musician Dan Gilroy, who wrote about her, “My dear, sweet, wonderful life partner and friend left us. Too much suffering lately, now she’s free. Fly away, beautiful Shelley.” In other words, transplendent.