“Smoke” was the perfect title for a movie written by the late Paul Auster. Not just because it’s set in and around a Brooklyn cigar store but because smoke has a shape that is ever-changing and ephemeral: within moments of creating it, it’s gone. And it’s produced through the transmutation of matter from one form to another, in the form of fire: creation, destruction. Sorry if it seems like my mind is pinballing even more often than usual, but Auster’s fiction did it, too, in a different way, and it’s contagious. Auster’s prose was sinuous and graceful, his storytelling playful and digressive. You never knew what would happen from one paragraph to the next.

The first movie based on one of his books was Philip Haas’s “The Music of Chance,” an absurdist tale perched right on the edge of fairytale/metaphor about a couple of unlikely buddies (Mandy Patinkin and James Spader) who become pawns and slaves on the estate of a couple of rich men (Charles Durning and M Emmett Walsh). I hadn’t read the novel when I saw the film and was genuinely surprised by all the different modes it contained and how matter-of-factly it jumped between them.

Spun off from a short story Auster wrote for The New York Times, “Smoke” is tonally more even but just as far-reaching and playful in its storytelling. Directed by Wayne Wang (“The Joy Luck Club,” “Chan is Missing”) from a script by Auster, it’s an ensemble movie about daily life in a changing neighborhood: Park Slope, Brooklyn, which was predominantly black and poor in the 1960s and ’70s (in Hal Ashby’s 1970 debut film “The Landlord,” a rich Connecticut trust fund kid impulsively decides to buy a house there, and his horrified mother exclaims, “But that’s a ghetto!”). The area started to gentrify in the mid-eighties and was beginning to turn yuppie by the mid-’90s, when the film was shot. The characters talk about what’s happening to their community and many other things.

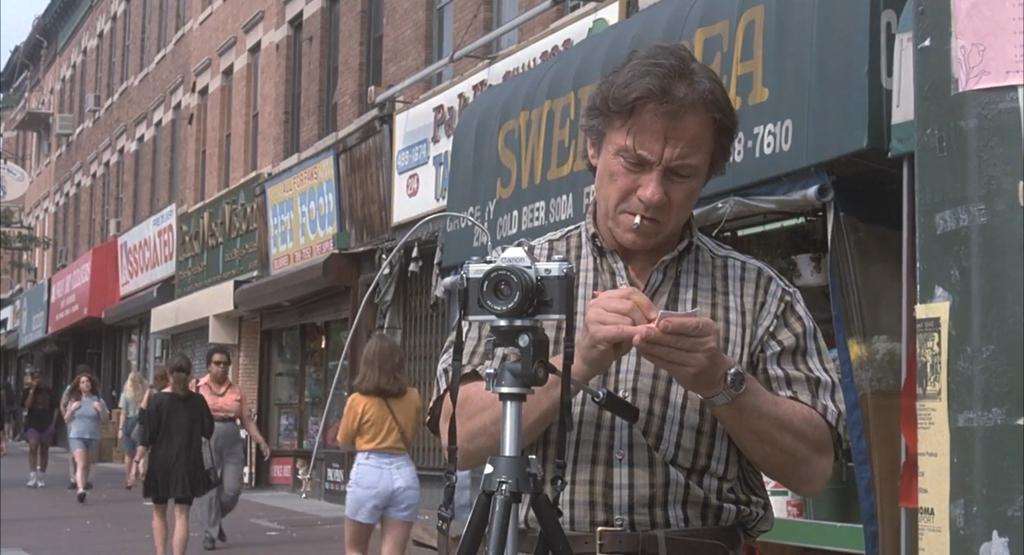

The main characters of “Smoke” are a cigar store owner named Auggie Wren (Harvey Keitel), who takes photos of the neighborhood from the same spot at 8 a.m. every day, and a scruffy, philosophical writer named, er, Paul (last name Benjamin) who recently lost his wife. A young, poor teenager named Rashid (an early knockout performance from Harold Perrineau) enters Paul’s life, and it seems for a while as if he’s going to become a surrogate son to him. But life is complicated.

There are all sorts of neighborhood eccentrics circling around Auggie, Paul, and Rashid, including a gas station owner named Cyrus (Forest Whitaker) who denies that Rashid is his son; Auggie’s ex-girlfriend Ruby McNutt (Stockard Channing), who shows up to tell Auggie that he has a teenage daughter who’s on drugs and needs money for rehab; and a couple of off-track betting parlor regulars (Giancarlo Esposito and José Zúñiga) who are named Tom and Jerry after the cartoon cat and mouse.

There were a lot of small films like “Smoke” being made in the 1990s in the United States: ensemble comedies or dramas (or some combination) that told a story but were mainly about capturing the peculiarities of the human personality and the vibe of neighborhoods and/or subcultures. A shockingly high percentage of them were good to excellent: “Barcelona,” “Walking and Talking,” “Sling Blade,” “Trees Lounge” and “Big Night” are a few examples. “Smoke” is one of the best.

Many of the most memorable scenes just put a camera in a space and watch people talk to each other, like when Paul goes into the store to buy some cigarettes and ends up telling the other guys a story. It starts when Auggie tells Paul that when he entered the store, he and Tom and Jerry were just talking about “women and cigars. Paul asks, “Ya ever hear of Sir Walter Raleigh?” and Tom says, “Yeah, sure, that’s the guy who threw his cloak down over that puddle.” “I used to smoke Raleigh cigarettes,” Jerry offers. Then Paul tells the story of how Sir Walter Raleigh introduced tobacco to the court of Queen Elizabeth II, leading to a bet on whether it was possible to measure the weight of smoke (a wonderful phrase that could’ve been the title of yet another Paul Auster book).

It often feels as if the characters are talking not just to hear themselves speak but to lend ephemeral sensations and memories the illusion of permanence, however momentary. “The pen will never be able to move fast enough to write down every word discovered in the space of memory,” Auster wrote in The Invention of Solitude. “Some things have been lost forever, other things will perhaps be remembered again, and still other things have been lost and found and lost again. There is no way to be sure of any this.”

“Smoke” is also notable for being one of a handful of great “package deal” movies wherein more than one feature was shot in immediate succession or at the same time. Among the best “two-fer” movies are Monte Hellman’s “The Shooting” and “Ride in the Whirlwind,” low-budget Westerns starring Jack Nicholson, who cowrote one of them. The other half of the “Smoke” package is “Blue in the Face,” shot in five days after the conclusion of “Smoke” (with Harvey Keitel again anchoring the ensemble). These Wang-Auster collaborations belong on the short list of all-time great twofer productions.

A lot of “Blue of the Face” is built around ad-libs, shot in between scenes during the production of “Smoke.” Auster co-directed the movie, his first such credit. He went on to write and direct “Lulu on the Bridge” and “The Inner Life of Martin Frost,” a couple of odd, mysterious, atmospheric dramas; both are worth a look. The characters in “Blue in the Face” are mostly new faces that did not appear in “Smoke.” Sometimes, it feels a bit like a celebrity drop-in party; Roseanne Barr, Lily Tomlin, Michael J. Fox, Jim Jarmusch, RuPaul, and Lou Reed all show up briefly. “Blue in the Face” is no kind of classic and probably not “necessary” (whatever that word means in relation to art; people sure do use it a lot online, for some reason). But it’s fun for fans of “Smoke.” It’s looser, broader, and doesn’t feel as deliberate. Think of it as the movie equivalent of a bonus disc of outtakes of a band jamming, recorded at the same time as an album with actual songs.

Both films get close to that impossible goal of measuring the weight of smoke or, alternately, catching lightning in a bottle. Reviewing Auster’s 2010 novel “Sunset Park,” another one of his classics about the life of a neighborhood and its citizens, novelist Malena Watrous wrote, “his characters still mourn the passing moment even as they live in it, still yearn to hold on to the present even as it slips away.” That line describes a lot of the characters in “Smoke,” who verbalize their way through lives in which decay, evolution, and time itself remain invisible, even though evidence of their handwork is everywhere.