When they finished writing the script for “Star Trek IV,” they must have had a lot of silly grins on their faces. This is easily the most absurd of the “Star Trek” stories – and yet, oddly enough, it is also the best, the funniest and the most enjoyable in simple human terms. I’m relieved that nothing like restraint or common sense stood in their way.

The movie opens with some leftover business from the previous movie, including the Klingon ambassador’s protests before the Federation Council. These scenes have very little to do with the rest of the movie, and yet they provide a certain reassurance (like James Bond’s ritual flirtation with Miss Moneypenny) that the series remembers it has a history.

The crew of the Starship Enterprise is still marooned on a faraway planet with the Klingon starship they commandeered in “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.” They vote to return home aboard the alien vessel, but on the way they encounter a strange deep-space probe. It is sending out signals in an unknown language which, when deciphered, turns out to be the song of the humpback whale.

It’s at about this point that the script conferences must have really taken off. See if you can follow this: The Enterprise crew determines that the probe is zeroing in on Earth, and that if no humpback songs are picked up in response, the planet may well be destroyed. Therefore, the crew’s mission becomes clear: Because humpback whales are extinct in the 23rd century, they must journey back through time to the 20th century, obtain some humpback whales, and return with them to the future – thus saving Earth. After they thought up this notion, I hope the writers lit up cigars.

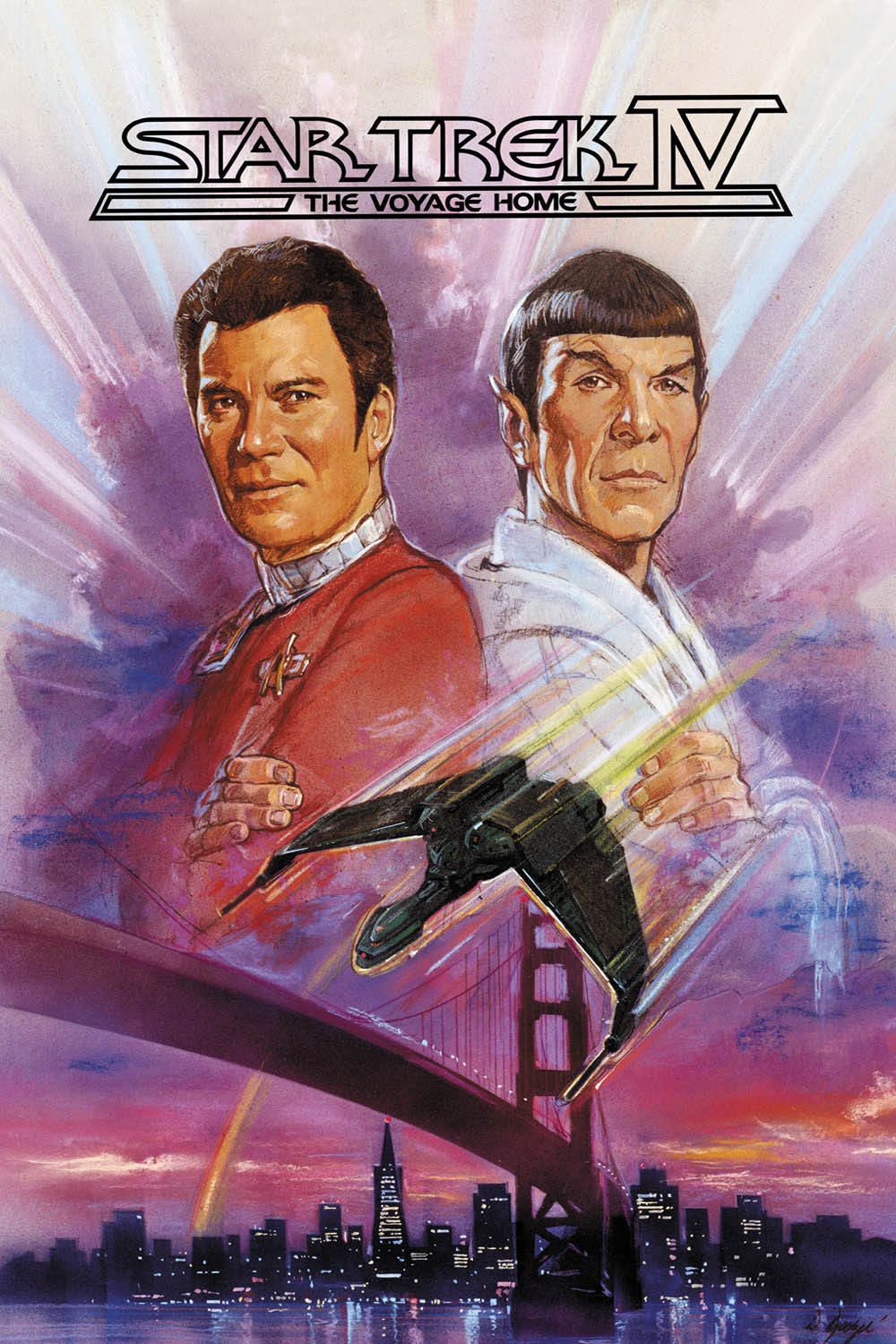

No matter how unlikely the story is, it supplies what is probably the best of the “Star Trek” movies so far, directed with calm professionalism by Leonard Nimoy. What happens is that the Enterprise crew land their Klingon starship in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, surround it with an invisibility shield, and fan out through the Bay area looking for humpback whales and a ready source of cheap nuclear power.

What makes their search entertaining is that we already know the crew members so well. The cast’s easy interaction is unique among movies, because it hasn’t been learned in a few weeks of rehearsal or shooting; this is the 20th anniversary of “Star Trek,” and most of these actors have been working together for most of their professional lives. These characters know one another.

An example: Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and Mr. Spock (Nimoy) visit a Sea World-type operation, where two humpback whales are held in captivity. Catherine Hicks, as the marine biologist in charge, plans to release the whales, and the Enterprise crew need to learn her plans so they can recapture the whales and transport them into the future.

Naturally, this requires the two men to ask Hicks out to dinner.

She asks if they like Italian food, and Kirk and Spock do a delightful little verbal ballet based on the running gag that Spock, as a Vulcan, cannot tell a lie. Find another space opera in which verbal counterpoint creates humor.

The plots of the previous “Star Trek” movies have centered around dramatic villains, such as Khan, the dreaded genius played by Ricardo Montalban in “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.” This time, the villains are faceless: the international hunters who continue to pursue and massacre whales despite clear indications they will drive these noble mammals from the Earth. “To hunt a race to extinction is not logical,” Spock calmly observes, but we see shocking footage of whalers doing just that.

Instead of providing a single human villain as counterpoint, “Star Trek IV” provides a heroine, in Hicks. She obviously is moved by the plight of the whales, and although at first she understandably doubts Kirk’s story that he comes from the 23rd century, eventually she enlists in the cause and even insists on returning to the future with them, because of course, without humpback whales, the 23rd century also lacks humpback whale experts.

There are some major action sequences in the movie, but they aren’t the high points; the “Star Trek” saga has always depended more on human interaction and thoughtful, cause-oriented plots. What happens in San Francisco is much more interesting than what happens in outer space, and this movie, which might seem to have an unlikely and ungainly plot, is actually the most elegant and satisfying “Star Trek” film so far.