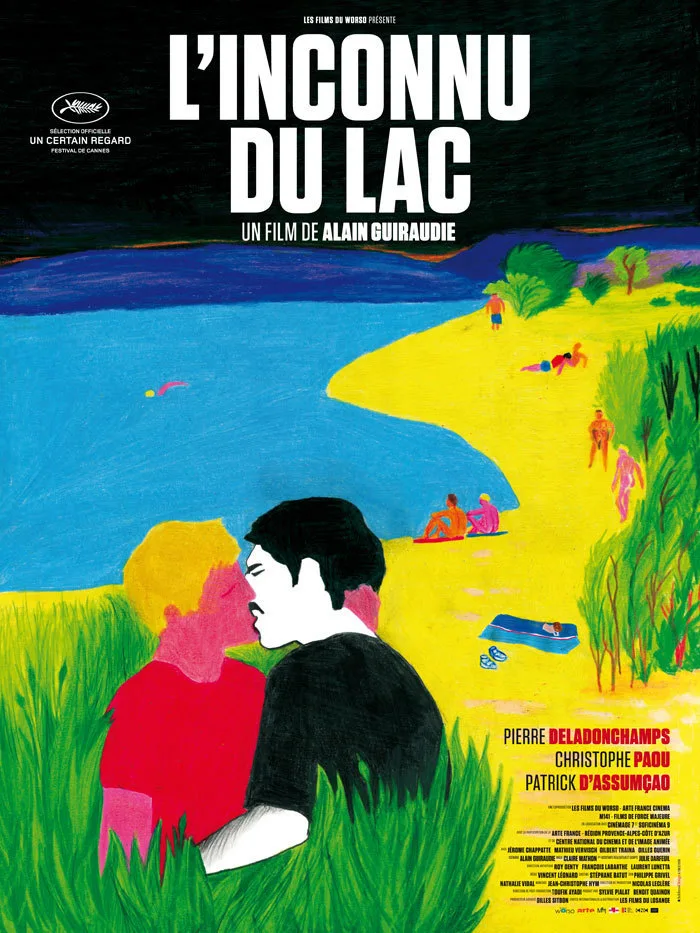

“Stranger by the Lake” is the sexiest and most elegant thriller in years, and it’s a damn shame it stands so little chance of traveling beyond the niche of a “gay film” it will probably get squeezed into. This French movie, written and directed by Alain Guiraudie, is set in a single location and has a dreamy quality to it: a mixture of allure and menace that’s quite intoxicating. We never leave a sunny gay cruising area the characters are frequenting—a lake, a beach, a nearby boudoir of bushes—but our imagination is kept alert at all times: every image and every cut is underlined with tension.

The main character is Franck (Pierre Deladonchamps), an attractive guy in his thirties regularly enjoying everything the cruising spot has to offer: from a chat to a swim to a tryst. We meet him on the day he strikes up a conversation with Henri (Patrick D’Assumçao), the flabby and gruff lumberjack who may alienate himself from the beach community, but seems open enough to Franck. And while the latter enjoys Henri’s company, he falls in love with Michel (Christophe Paou), a sexy and mysterious Tom Selleck lookalike the entire beach is smitten with (he’s like a mid-1980s gay centerfold incarnate).

Michel is initially aloof and goes to the bushes with someone else, but the next day he hits on Franck and they have sex. Their chemistry is immediate and palpable, even if Michel doesn’t want to hear of committment (which Franck is keen on having). The way the story is set up, it’s the unpopular Henri who represents fidelity and emotional attachment, while Michel is pure sex—with a dash of death. [SPOILER IN THE NEXT PARAGRAPH]

The evening after their first adventure, Franck witnesses Michel drown another lover picked up on the beach in an extraordinary long shot that’s the film’s centerpiece. Instead of calling the police, he is drawn more and more towards Michel, even as local police starts an investigation. The unsmiling inspector assigned to the case (Jérôme Chappatte) is faced with a daunting task. He starts gathering information in a place designed for people to lose their official identities and plunge into unbridled desire. A cat-and-mouse game ensues, with Franck becoming literal prey in the final scenes, shot in the dark and more primal in their feel than any of the sexual encounters depicted thus far.

The entire microcosm of the film is highly ritualized: from the looks and gestures signaling erotic interest (or lack thereof) to the way individual characters move and interact. Henri’s arms are forever reclusively folded on his chest, the inspector holds his hands behind his back like a cartoon of a detective; and Michel seems forever ready for a photo shoot of his hairy chest and dazzling smile. Nudity may not be obligatory at the beach, but it is both welcome and rampant: I cannot think of any other movie that’s so open to naked male bodies and treats them so casually (the whole of the clothing in “Stranger by the Lake” would scarcely fill up one drawer). By immersing us so totally in the workings of the gay beach, Guiraudie avoided the trap of William Friedkin’s abysmal “Cruising“, which presented its milieu as a freak show. This film appears to have been made by a resident, not a tourist. There’s something tremendously liberating in seeing so much gay sexuality set against water, sand, grass and stars in the sky (you can imagine Walt Whitman approving).

It has to be said that the sex scenes are explicit (though some are shot in elegant silhouettes), but their explicit nature hardly accounts for their power. Thanks to the great acting of the entire cast, as well as the editing by Jean-Christophe Hym and cinematography by Claire Mathon, Guiraudie makes you feel the desire that drives Franck to the edge of self-destruction; Michel is just too damn yummy for him to resist. At the same time, “Stranger by the Lake” is an indictment of mainstream gay culture and its fixation on perfect, chiseled bodies (the community immediately marginalizes anyone not stereotypically attractive). At times, the film almost becomes a medieval fable about the danger of encountering carnal perfection that’s borderline inhuman.

Guiraudie’s directorial assurance is stunning: the entire movie is a master class in audiovisual storytelling, as well as an exemplary case of immersing the viewer in an environment. From the choice of the titular lake (pretty but not gorgeous), to the beautiful details of the changing sunlight, play of shadows on naked skin, and the near-enchanted quality of the surrounding forest, Guiraudie creates a coherent world we immediately feel like we inhabit. The recurring shots of a parking lot serve both as punctuation and a narrative device (the day after the body is found there’s hardly a car in sight), and the production design makes it purposefully unclear what era are we exactly in (mid-1990s is most likely: there’s already AIDS awareness instead of AIDS panic, but no one owns a cell phone).

If there’s some austerity to the film (and to character of Franck), it’s softened not only by Henri’s affable grumpiness, but also by the recurring appearances of Eric (Mathieu Vervisch): a puppy-like peeping tom, always eager to watch other guys have sex as he pleasures himself in bliss. Shots of Eric materializing out of nowhere are the great running joke of the film, but the character is never mocked or judged. Some guys, like the high-strung lover we first see Franck have sex with, are harsh with him, but Guiraudie is not. He shows Eric’s total infatuation with Franck in a gentle, sympathetic manner, so that when Eric finally makes his big move and shares a beach towel with the object his desire, the moment is irresistible—not least to Franck.

Guiraudie, who first drew my attention in 2009 with the supreme “King of Escape” (a comedy of a gay man discovering he’s madly in love with a woman), is definitely flirting with Hitchcock in “Stranger of the Lake”, and some of the cutting is instantly recognizable as an homage. However, the complete lack of musical score (replaced by chirping birds, water lapping against the shore, and lovers panting in ecstasy), makes the film something more than a thriller—at its very best, it’s a meditation on the nature od friendship and desire, as well as the maddening incongruity of the two.