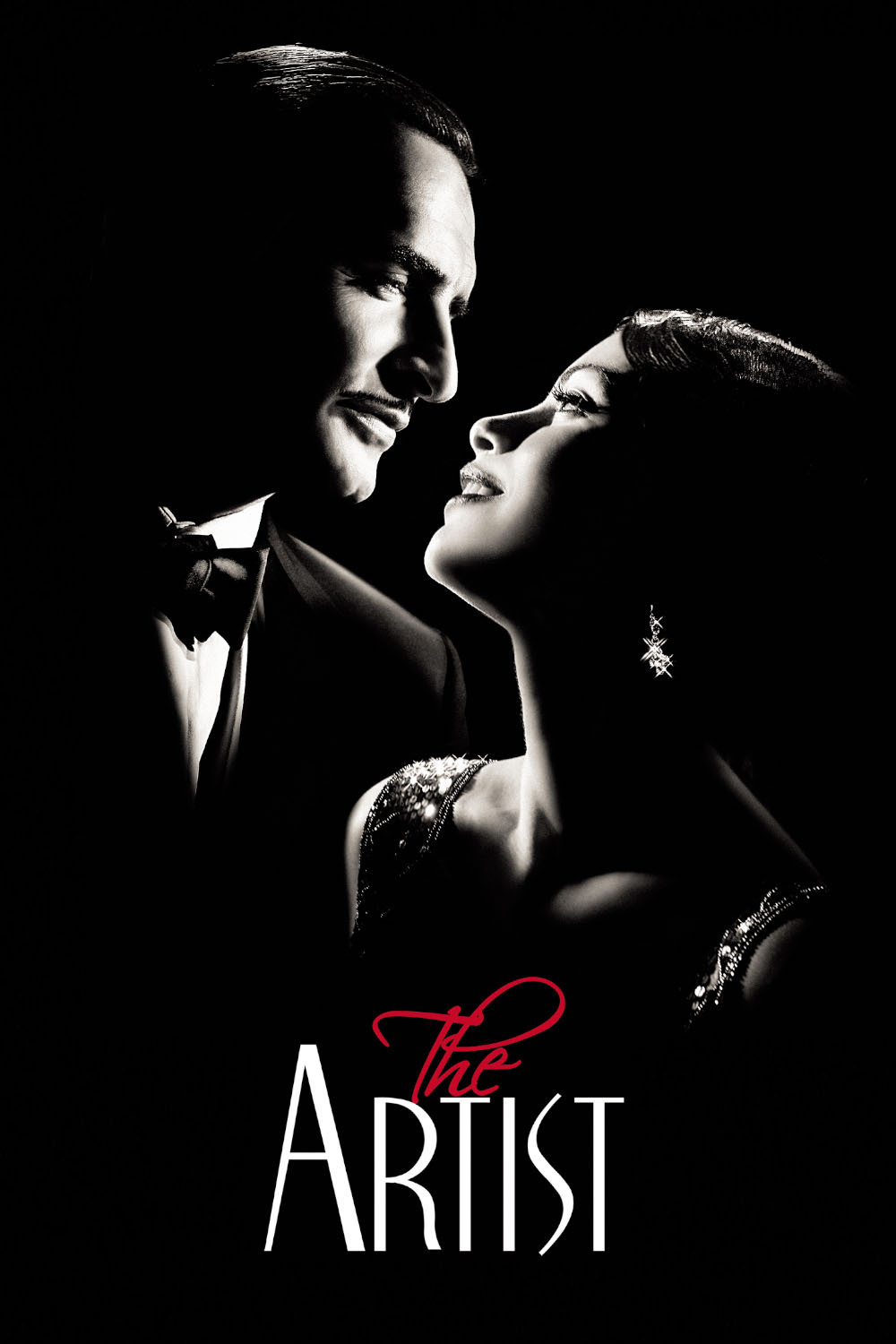

Is it possible to forget that “The Artist” is a silent film in black and white, and simply focus on it as a movie? No? That’s what people seem to zero in on. They cannot imagine themselves seeing such a thing. At a sneak preview screening here, a few audience members actually walked out, saying they didn’t like silent films. I was reminded of the time a reader called me to ask about an Ingmar Bergman film. “I think it’s the best film of the year,” I said. “Oh,” she said, “that doesn’t sound like anything we’d like to see.”

Here is one of the most entertaining films in many a moon, a film that charms because of its story, its performances and because of the sly way it plays with being silent and black and white. “The Artist” knows you’re aware it’s silent and kids you about it. Not that it’s entirely silent, of course; like all silent films were, it’s accompanied by music. You know — like in a regular movie when nobody’s talking?

One of its inspirations was probably “Singin' in the Rain,” a classic about a silent actress whose squeaky voice didn’t work in talkies and about the perky little unknown actress who made it big because hers did. In that film, the heroine (Debbie Reynolds) fell in love with an egomaniacal silent star — but a nice one, you know? Played by Gene Kelly in 1952 and by Jean Dujardin now, he has one of those dazzling smiles you suspect dazzles no one more than himself. Dujardin, who won best actor at Cannes 2011, looks like a cross between Kelly and Sean Connery, and has such a command of comic timing and body language that he might have been — well, a silent star.

Dujardin is George Valentin, who has a French accent that sounds just right in Hollywood silent films, if you see what I mean. The industry brushes him aside when the pictures start to speak, and he’s left alone and forlorn in a shabby apartment with only his faithful dog, Uggie, for company.

At a crucial moment, he’s loyally befriended by Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo), who when they first met, was a hopeful dancer and has now found great fame. The fans love her little beauty mark, which Valentin penciled in with love when she was a nobody.

As was often the case in those days, the cast of “The Artist” includes actors with many different native tongues, because what difference did it make? John Goodman makes a bombastic studio head, and such familiar faces as James Cromwell, Penelope Ann Miller, Missi Pyle and Ed Lauter turn up.

At 39, Jean Dujardin is well-known in France. I’ve seen him in a successful series of spoofs about OSS 117, a Gallic secret agent who mixes elements of 007 and Inspector Clouseau. He would indeed have made a great silent star. His face is almost too open and expressive for sound, except comedy. As Norma Desmond, the proud silent star in “Sunset Boulevard,” hisses: “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces!” Dujardin’s face serves perfectly for the purposes here. More than some silent actors, he can play subtle as well as broad, and that allows him to negotiate the hazards of some unbridled melodrama at the end. I felt a great affection for him.

I’ve seen “The Artist” three times, and each time it was applauded, perhaps because the audience was surprised at itself for liking it so much. It’s good for holiday time, speaking to all ages in a universal language. Silent films can weave a unique enchantment. During a good one, I fall into a reverie, an encompassing absorption that drops me out of time.

I also love black and white, which some people assume they don’t like. For me, it’s more stylized and less realistic than color, more dreamlike, more concerned with essences than details. Giving a speech once, I was asked by parents what to do about their kids who wouldn’t watch B&W. “Do what Bergman’s father did to punish him,” I advised. “Put them in a dark closet and say you hope the mice don’t run up their legs.”