The horror potential of “The Blackcoat’s Daughter” peeks through in its richly textured and sensual soundtrack. Beyond the score’s guttural beats, white noise pierces through silence and isolated sounds like a mournful wail and a knife plunging through flesh echo, producing a distinct sense of discomfort. Written and directed by Oz Perkins, this is a horror film built around elliptical vagaries, as the story of three young women bound by their connection to an isolated boarding school unfolds with clandestine non-linearity.

In spite of some compelling performances and a consistent mood, the film fails to ground any of these aesthetic flourishes in story or emotion. Perkins may have the sense to draw on a glacial winter environment as a mood setter but he fails to move beyond the surface. While set at a Catholic boarding school for girls, the full potential of that alien environment remains a convenient tool for isolation rather than a part of the film’s thematic structure. Nearly every scene is built around a slow zoom or an awkward pause, and establishing shots focus on eerily framed empty classrooms, but that approach does little to disguise the film’s lack of substance.

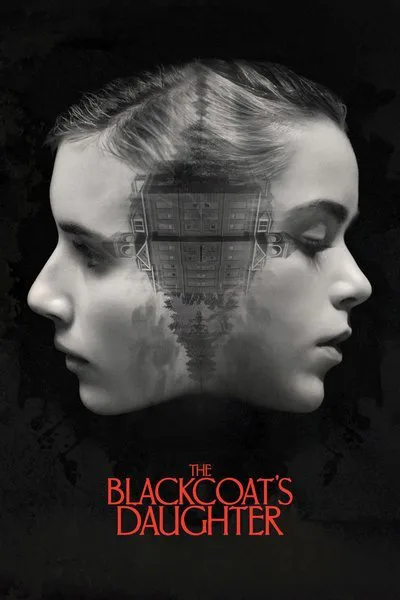

All three leads (Emma Roberts, Kiernan Shipka, and Lucy Boynton) are compelling to watch though they all seem restrained by a uniform tone. Too much of the film’s mood and sense of character is defined by stilted aloofness, marked by awkward pauses and monotone line deliveries, robbing the film of variance and richness. The gap between the characters purported to be disturbed and those who are merely bystanders is too narrow, a failure of writing and direction rather than performance.

The non-linear story fails to enrich the experience and only serves to obscure information in a cheap plea for suspense. Too much information is withheld without a sense of purpose, tipping the film too deeply into ambiguity and vagueness. Any sense of dread that the movie inspires comes from a kind of incompleteness, like a song being cut off before its final notes, rather than a sense of discomfort drawn from difficult ideas or feelings. What we know about the characters is spelled out by dialogue and relies on our assumptions of high school stereotypes as we fill in the gaps of how a keener, a popular girl, and an outsider might behave. Rose (Lucy Boynton), for example, the pretty popular girl who might be pregnant, feels like a walking after-school special. She might not be an obvious stereotype (her aloofness guarantees it) but she is never defined by anything than her beautiful face. The structure similarly does little to justify the inclusion of Emma Roberts’ character, who is defined by her mysteriousness and little else. For fear of spoilers, it’s difficult to delve too deeply into this element of the story, but her tie-in to the rest of the film lacks a satisfying pay-off.

The movie could easily be a sister film to last year’s “The Eyes of My Mother,” another horror that failed to wow me. While many of the similarities are superficial, both films are about young women gripped with bloodlust due in part to alienation, and they also build their horror through aesthetics. The comparison also serves to highlight that while this film was lacking for me, there is an art-house horror audience that thrives on these stories and feels compelled to fill in gaps that I personally find difficult to overlook. Both movies seem inspired by classics of neurotic femininity like “Repulsion” and “3 Women,” but lack the characterizations and ambition to make it work. The film’s biggest risk, adopting a non-traditional narrative structure, cannot overcome the fact that the story itself has little to say about what it means to be a teenage girl and how loneliness can act as a possessing agent of the devil.

Above all else, the film’s greatest failure is its inability to channel the story through emotion, spreading itself thin across themes of alienation, mourning and fears of abandonment. As the movie relies more heavily on aesthetics than story, greater focus would have led to a more cohesive film. Rather than an empty and sometimes frustratingly unfocused story, it could have been an effective tone poem. Without giving any one of these anxieties enough space to evolve, it fails to channel any one of them in a particularly effective way.