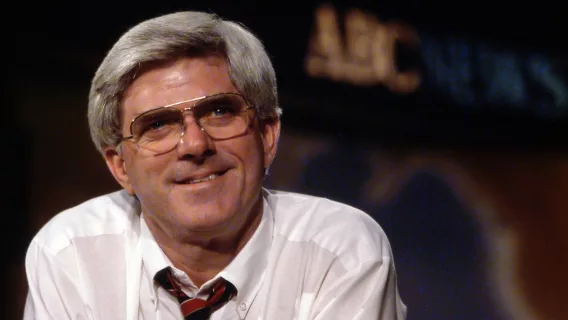

Wilmer “Bill” Butler, the cinematographer who will forever be linked with his work on “Jaws” (1975), left us on April 5, 2023, just two days shy of his 102nd birthday. A Colorado boy, he was born in a log cabin in 1921 in the tiny mining community of Cripple Creek before moving to Iowa with his farming family the year before “The Jazz Singer” introduced the notion of a “talkie” to motion pictures. An engineer by training, Bill got into the tech side of radio in Gary, Indiana, before helping to build WGN’s first television studios in Chicago. Curiosity in the new technology piqued, he picked up a camera where he cut his teeth shooting “thousands” of shows and documentaries with abrasive, driven, upstart television director William Friedkin. One of them, his first feature, is called “The People Vs. Paul Crump” (1962). It’s a shockingly effective, evergreen documentary punctuated by dramatic recreations in a style now oft-attributed to Errol Morris, telling the story of a death row prisoner convicted of killing a guard during a botched robbery at a meat packing plant. Immediately pulled from the broadcast schedule for the allegations of torture and coercion leveled at the Chicago PD, Friedkin stole a copy of the confiscated film and showed it to then-Governor Otto Kerner who, a day later, commuted Crump’s execution.

It launched Friedkin’s career. And though Butler would return to shoot television often during his career, when Friedkin went to Hollywood, Bill went with him. While Friedkin was off helming a spoof called “Good Times” (1967) with Sonny & Cher, Bill shot Phil Kaufman’s Frankenstein comedy “Fearless Frank” (1967), notable as Jon Voight’s debut but also for Butler’s interest in the natural world; his gift for capturing the emotional intimacy of family relationships through effortless, unforced framing; his fondness for the slow push-in and extreme close-up to amplify tension; of key-lighting and even a closing-iris in-camera effect to draw attention to details in a scene; and for shooting from extreme high and low angles to provide visual interest and texture. When freshly-reanimated corpse Frank (Voight) foils a diabolical cat burglar in Fearless Frank, he punches the villain up a spiral staircase with one swing. Butler shoots the felon’s dazed mug from above so our sightline tracks all the way down and around to Frank, still at the bottom, looking up with one fist raised in the follow-through. Butler wasn’t ostentatious; he was succinct. Everything you needed to know, you get in one shot.

In simpler terms, Butler’s way of seeing, born of modest, tightly-knit roots, a farmer’s love for the outdoors, and an engineer’s and technological auto-didact’s ingenuity, helped to define the look of the greatest era of film in the history of the medium. Bill Butler grounded the incomprehensibility of the American ‘70s—its energy and cacophony; the feeling of change carried before a violent, anarchic gale. Already 46 years old during the Summer of Love, he wasn’t one of the “Film Brats,” that group of tousled trailblazers who filled the gulf left behind by a decrepit studio system that found itself out of step with the tastes of the Flower Power generation.

He was there for Jack Nicholson’s directorial debut “Drive, He Said” (1971). He was there, too, for Robert Culp’s first and only directorial effort, 1972’s tremendous and sadly underseen LA noir “Hickey & Boggs,” the first produced screenplay by a young writer named Walter Hill for which Butler re-used the sunset beach shot at the end of “Fearless Frank.” Then, much later, he shot actor Bill Paxton’s directorial debut “Frailty” (2001). In an interview with the Austin Chronicle in April of 2002, Paxton says “I wanted my first movie to have some great craft in all of the departments, and cinematically speaking, I knew that Bill Butler could do that.” If mentorship wasn’t a role Butler craved, it was one it seemed in which he was cast. Butler provided a look for “Frailty,” intimate and warm before it becomes insinuating and sinister, keyed in on the father/son dynamics that drive the piece.

Notably, he worked early on with two members of the New American Cinema’s crowded Mount Rushmore: Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg. Butler helped change moviemaking with Spielberg” on “Jaws,” and was the cinematographer for my favorite film of all time, and my pick for the best of what seems an impossibly deep, indeed inexhaustible well of great films and filmmakers in that “decade” between 1967 and 1981, Coppola’s “The Conversation” (1974). But Butler had worked with both filmmakers before. With Spielberg, he shot a pair of TV movies: the superlative possession/evil child movie (that dropped the year before “The Exorcist”) “Something Evil” (1972), and then a Martin Landau-starring investigative reporter saga “Savage” (1973). In “Something Evil,” you can see the formation of one of the genuine savants this medium has ever produced and, certainly, Spielberg deserves all the garlands he’s gathered in honor of his gifts.

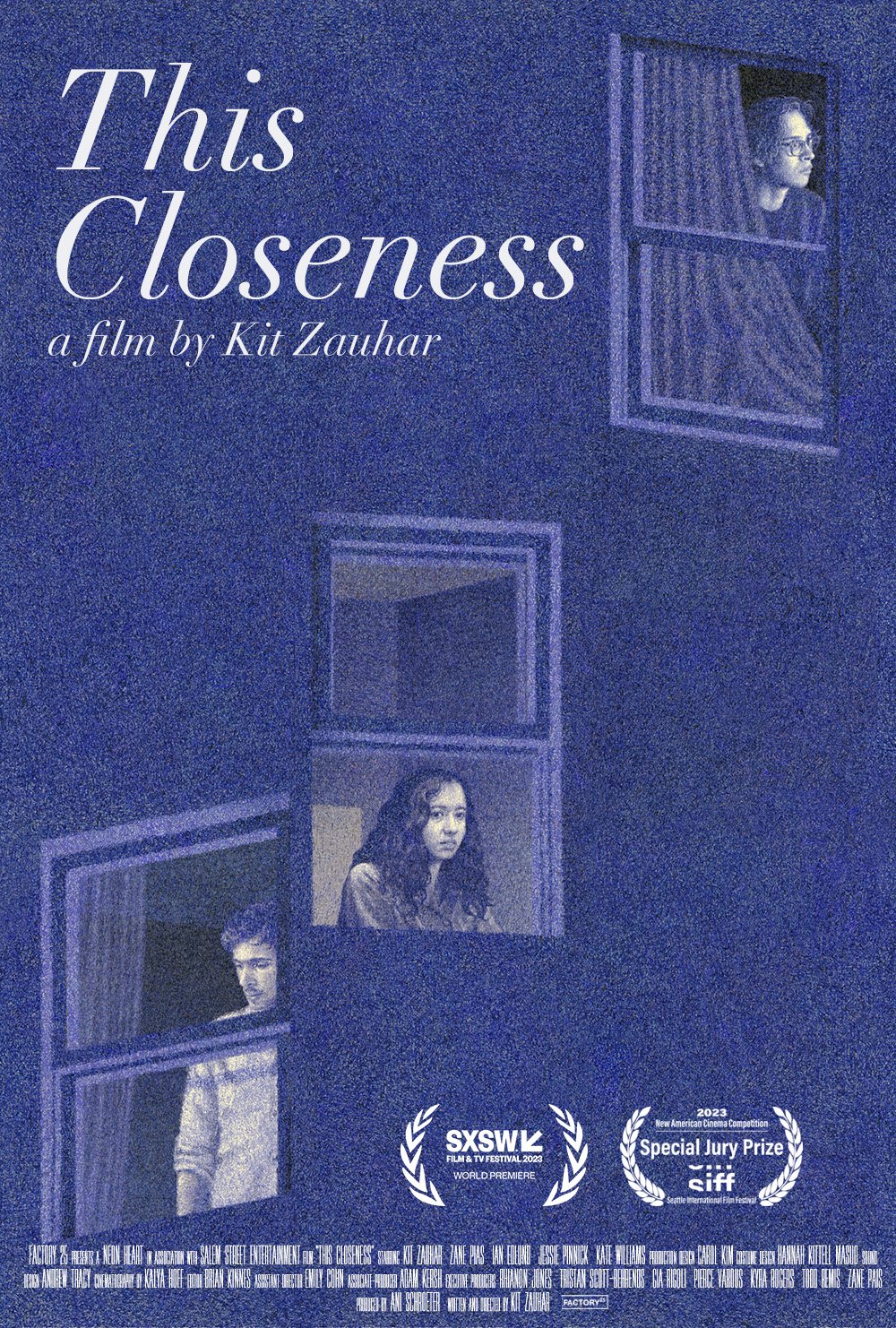

Once you’ve watched Bill Butler’s work all the way through the 1980s, a run that includes 53 films and also Daryl Duke’s enormously popular ABC miniseries “The Thorn Birds” (1983), an argument could be made that the genius already obvious in “Something Evil” is evidence of two great talents. Consider the high/low shots, the dramatic push-ins, the attack on Dennis’ housewife character Marjorie by vines in a bower, her sudden awareness of a malign presence shot in a closeup while the something evil of the title looms invisibly in the open space behind her. A scene comparison shows it to be the exact mirror of the scene from “Jaws” when Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) turns from his task of scooping chum at the moment Bruce the shark makes a surprising appearance. They were artists who complemented each other: Spielberg, who could see everything in his head, and Butler the engineer who could make it happen. When it came time for Spielberg to shoot on the open ocean, despite conventional wisdom that if it wasn’t outright impossible, it was at least profoundly inadvisable, of course, he turned to Bill Butler to rig it.

With Coppola, prior to “The Conversation,” Butler had shot the existential, meditative, melancholic road trip movie “The Rain People” (1969), a film so obsessed with interior spaces that the first real look we get at its star Shirley Knight is in extreme close-up against lime-green shower tiles, water hitting her face like a baptism into the new life the rest of the film dangles like a tease of a better world. What’s immediately evident in Butler’s work is his knowledge of space and perspective as they inform character. His characters are often trapped in frames within the film’s frame, intruded upon, appalled. My favorite moment in “The Conversation” comes when surveillance expert Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) invites a few industry peers and rivals to his workshop and stands, removed from them, listening to their revelry from behind a translucent scrim in his kitchen. The outline of Harry there works like a shadow puppet isolated in its own drama of loneliness, a Platonic metaphor just like his name “Caul,” or like his ridiculous plastic raincoat. A similar shadow play occurs a decade earlier in “The People vs. Paul Crump” when the stormtroopers of the Chicago penal community escort Crump from his cell Butler tells it all, the injustice and futility of it, in their shadows cast through iron bars.

Butler was more than a craftsman. He was a creator with predilections and hallmarks, and this group of creators—not just the marquee names like Friedkin, Coppola, Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Elaine May, Joan Micklin Silver, George Lucas and on and on, but people like Polly Platt, Walter Murch, Thelma Schoonmaker, Carole Eastman, and Monte Hellman too—that this group of creators was like Warhol’s Factory or the Bloomsbury Group, CBGB in the No Wave, or the Laurel Canyon scene, collaborating with one another, pushing, blending, evolving towards the manifestation of artifacts possessed of a pure, collective, cultural clarity. He’s not the person we remember from “Jaws” or “The Conversation,” but they wouldn’t be what they are without him. Butler should be spoken of in the same breath as Vittorio Storaro and Gordon Willis, Néstor Almendros, and Michael Chapman, but his work’s relative modesty makes it seem as though he’s doing less than what he is.

Once you’re keyed in on exactly what he does, you’ll see his fingerprints on other work you’ve known your entire life. Films like “Grease” or the first three sequels to “Rocky”; figure-skating tearjerker “Ice Castles”; one of my favorite films from my youth, John Badham’s “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings.” All of this and I’ve somehow not even gotten to his towering work on Milos Forman’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975), his second film in a row taking over from Haskell Wexler, who had also been fired from “The Conversation.” What was it these great filmmakers were looking for to replace the indisputably brilliant but mercurial and difficult Wexler? An artist? Yes, but a partner, too—a problem-solver who could enhance and share a vision. There can be no better praise for a cinematographer than that he brought focus to any project. What a gift it is to reconsider all of these masterworks through the lens of Bill Butler’s contributions to them. He was a titan, and there will not soon be another like him.