“The Funeral” is about the kinds of gangsters the Corleone family might have become, if they had all gone to college. It’s a film where violence is delayed by conversations about morality, where the younger brother has left-wing sympathies and strange kinks, where the leader of the family protests, “I have ideas. I read books.” This is not to say it is an intellectual movie, about professorial gangsters. What it really means is that its characters, members of a mob family in New York, are more tortured than they might otherwise have been because they know more, and think more. Ignorance may not always be bliss, but it is sometimes more comfortable than insight.

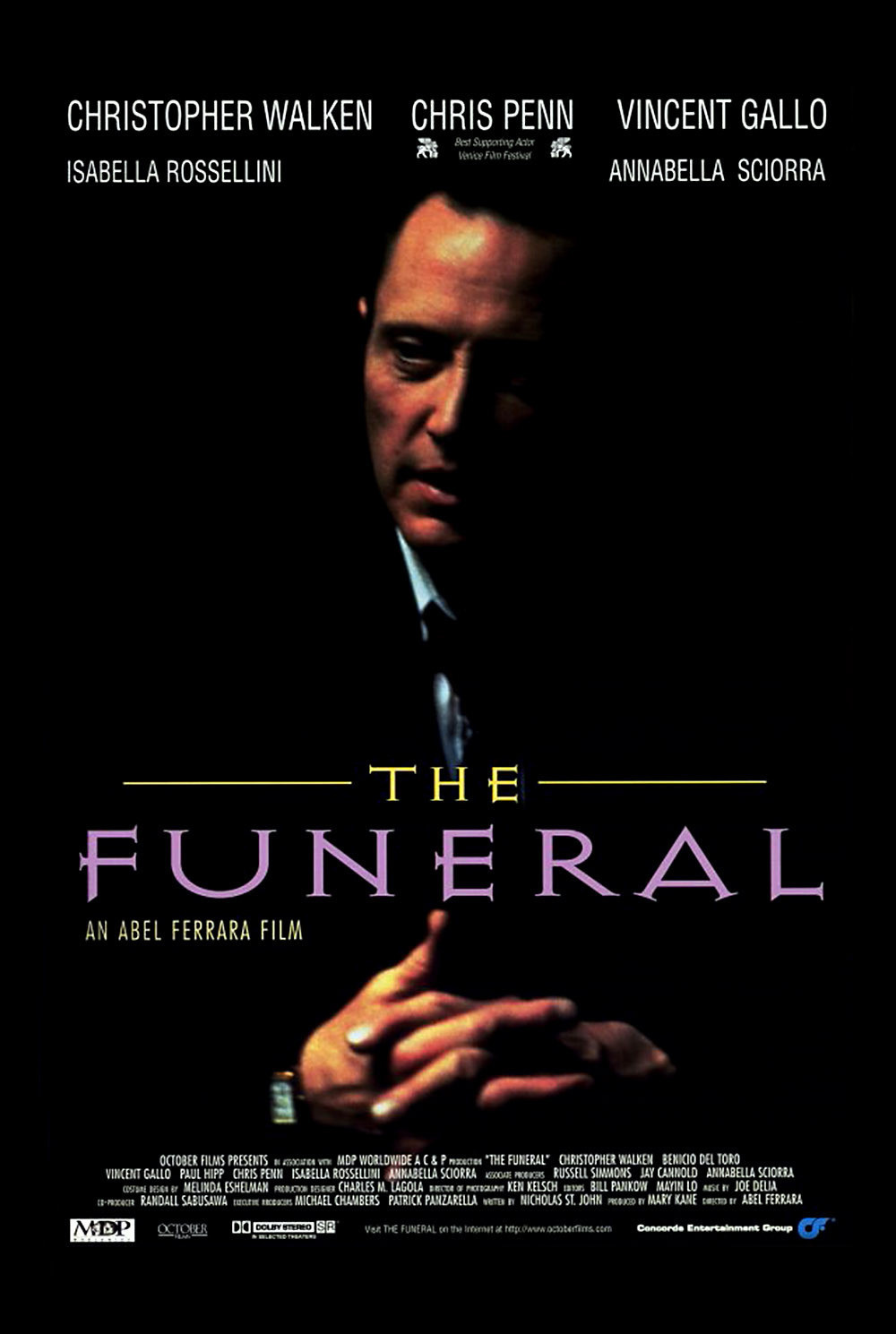

As the movie opens, Johnny Tempio (Vincent Gallo), the youngest of three brothers, has been brought home dead from a shooting. Greeting his corpse are his older brothers Ray (Christopher Walken) and Chez (Chris Penn), and the women of the family, played by Annabella Sciorra and Isabella Rossellini. Chez is a hot-blooded bartender, so enraged by the death that he attacks a flower delivery man and goes berserk at the side of the coffin. Ray is more dangerous, slick and controlled.

The death of the brother must be avenged, but first it is important that we understand how Johnny brought about his own doom, and how it may have been fated by deep currents within his own family. “The only way anything is going to change,” a priest observes, “is if this family has a total reversal.” The director, Abel Ferrara, uses flashbacks to lead us back up to the murder, showing Johnny as a misfit even within a family of misfits, a mobster assigned to work with a mob-connected union, who attends a workers’ meeting and perhaps even feels some sympathy with the communists who are haranguing it. He has odd tastes for a young man; at a stag party, he passes over the prostitutes who are available to choose the old, fat madam.

Ferrara has tried this before, crossing a genre movie with sneaky intellectual side-currents. His “China Girl,” about race hatred on the divide between Little Italy and Chinatown, was based on “Romeo and Juliet.” His “The Addiction,” a vampire movie, was set within the milieu of a graduate school of psychology (a vampire struck her victims at a party celebrating a doctorate). Here we have gangsters who brood and judge and apply moral standards. Chez, the “nicest” brother despite his temper, tries to give a girl $5 and send her home because he wants to rescue her from prostitution. She holds out for $10. He gives her $20, “because you just sold your soul.” The family’s libidos have crossed paths with the woman of a rival gangster, played by Benicio Del Toro, and that leads to violence, but not directly (nothing is direct in this film). Flashbacks, murky memories and oblique but knowing comments by the women hint of shocking secrets, and Ferrara draws a veil back just long enough for us to observe and speculate, but not long enough for us to be sure of what we should conclude.

The movie doesn’t have a traditional ending, or indeed a satisfactory one; “The Funeral” sets up more dilemmas than it can solve. Much of its appeal is in the acting. Chris Penn won the best supporting actor award at the 1996 Venice festival (where the film won the special jury prize), but his performance seemed to me well within his reach.

The actor I kept my eye on was Walken, who has an ability to hold his characters aloof from commitment; we’re not sure how much is real, and how much is an act or strategy. He, too, is an intellectual here, and there is a scene where, holding an ax, he considers killing a character he knows does not really deserve to die. He arrives at a logical conclusion: “Since you’re never going to forget this–you leave me no choice.” The guy is doomed not for what he did, but because of what the Walken character has done in response to it.

Abel Ferrara’s material is some of the darkest now being used in American film–hard noir. His version of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” was frightening in a way that turned the two earlier versions of the film into parables. His “Bad Lieutenant” gave us one of Harvey Keitel’s most unsettling performances, as a man so fundamentally twisted that he made conventional movie villains look like pretenders. Now here is a gangster movie that does not want setups or payoffs like traditional gangster movies. Other gangster movies focus on crime families. Ferrara links his family with its currently fashionable companion word, dysfunctional.