Your answer to “Why Adolf Hitler, still?” might depend on your overall view of the world, and whether you think humanity is inherently good or inherently bad, and if you consider modern society a scourge upon the earth, or the only thing that can save it. Has the Internet been a great equalizer or an irredeemably flawed cesspool? Does free speech cover hate speech? Have we, as an international collective, been effective enough in educating people about what Hitler did, and about the devastating impact of Nazi Germany’s actions? Or will Hitler linger as a specter of fascination (and even inspiration) for generations to come, even as time takes us further away from the atrocities of World War II?

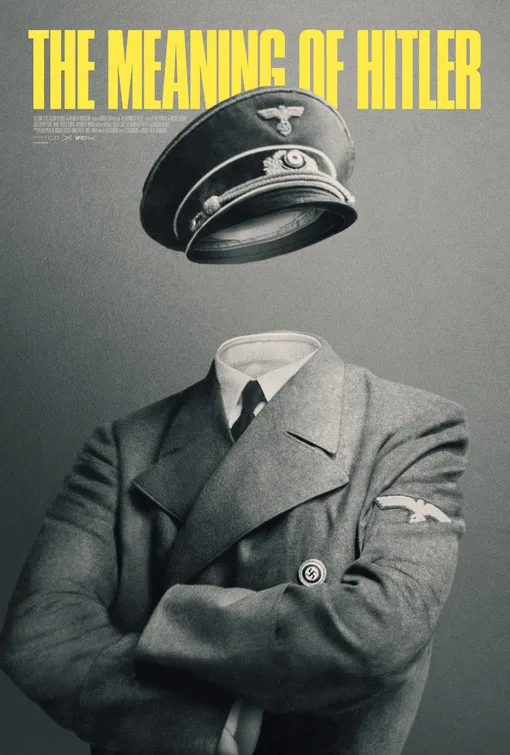

Inspired by the 1978 nonfiction book The Meaning of Hitler by German journalist Raimund Pretzel (writing under the pseudonym Sebastian Haffner), Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker’s same-named documentary parses through these questions to unravel the cultural captivation still swirling around Hitler. Why do we continue to make movies, TV shows, and documentaries about him? (looking at you, History Channel!) How do TikTok stars in their 20s and 30s decide to use to Hitler to shock (and draw in) viewers? Why do far-right movements in the United States and Europe still use the iconography mythologized in Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 propaganda film, “Triumph of the Will”? What possibly new facts about Hitler could be revealed in the dozens of books that are published about him each year? And even when we analyze Hitler’s words by reassessing them from a contemporary perspective, are we responsible if someone reads Mein Kampf and is radicalized instead of enraged?

There are numerous ways to investigate the myriad industries that have built up around Hitler, and the shortcoming of “The Meaning of Hitler” is that it tries to tackle them all. Epperlein, who appears onscreen reading Haffner’s book, acknowledges in her narration that the existence of this documentary might help feed the phenomenon it is attempting to criticize. But “The Meaning of Hitler” then throws too wide of a net, jumping from subject to subject to understand the various ways Hitler’s toxicity has continued to spread after his death. History, social media, Hollywood, art, contemporary politics—“The Meaning of Hitler” scrutinizes each of these areas before switching focus to something else, and the rapidity by which it does so is a mistake.

Like Pretzel’s book, the documentary is divided into various segments that examine aspects of Hitler’s aura, image, and ego. But Epperlein and Tucker’s “chapter” titles indicate the extremely dry humor they bring to this project: “Antisemitism” stands alongside “Hitler Had No Friends” and “The Good Nazi Years.” The filmmakers are summarily direct in their use of visual flourishes (onscreen text like “RADICAL LOSER” in blocky, blood-red letters), certain quotes (“As an artist, he was not that good,” U.S. Army Center of Military History Chief of Art Sarah Forgey says of Hitler), and their own narrated questions. “Why does Hollywood grant Hitler the kind of honorable death that is never given to his victims?” Epperlein wonders after a montage of death scenes from forgotten films about Hitler, including Anthony Hopkins’ Emmy-winning turn in the 1981 film “The Bunker”—but it feels a bit like a missed opportunity to not call to the carpet anyone from the industry about why these movies keep getting made. Overall, the filmmakers’ freewheeling approach covers a fair amount of ground, if somewhat superficially. Instead, it is the array of voices assembled here who often crystallize in their individual interviews what “The Meaning of Hitler” might not achieve in a holistic way.

Novelist Martin Amis says Hitler “resists understanding”; Israeli historian and professor Yehuda Bauer scoffs at the attempt to even do so (“You cannot put Hitler on a psychologist’s couch”); psychiatrist Dr. Peter Theiss-Abendroth warily lists all the diagnoses numerous people have, with no evidence, linked to Hitler as explanations for his actions. Historian and professor Saul Friedlander, whose parents were killed at Auschwitz, speaks of Hitler’s performative quality and warns of “propaganda … repackaged as reality.” Novelist Francine Prose says of “Triumph of the Will,” “It makes your flesh curl,” and Berlin Story Bunker museum curator Enno Lenze, can’t hide the bewilderment in his voice when he says that many American visitors ask him during the tour, “But are you sure that he is dead?”

The tension between reality and “fake news” is omnipresent in “The Meaning of Hitler” not just because the documentary repeatedly compares Hitler with former President Donald J. Trump, but also because of the inclusion of various Holocaust deniers, from online social media stars and personalities like PewDiePie to disgraced English historian David Irving. One of the great joys of “The Meaning of Hitler” is Friedlander’s dismissive delivery of “David Irving, please,” when asked about him, while one of the documentary’s most curdling moments is Irving, caught on a hot mic outside of the Treblinka extermination camp, saying to a laughing audience: “Jews … they don’t like any kind of manual work. They just like writing receipts.”

Irving’s presence shifts “The Meaning of Hitler” from looking backward, which it does by touring formative locations for Hitler in Austria and Germany and relying on archival footage of his speeches and rallies, to looking around now and wondering if we can ever shake free of his grasp. In discussing nationalism, the filmmakers cut from a World Cup celebration in France to a far-right demonstration in Poland; when introducing the chapter “The Hitler Cult,” audio from one of Trump’s speeches plays. These connections help drive home the filmmakers’ central idea that we’re still living under the shadow of the kind of authoritarianism and hate that Hitler championed. However: What can we do about it? Documentaries don’t have to be directive, but “The Meaning of Hitler” ends on a feeling of incompletion. Perhaps that’s thematically purposeful. As Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld says, “History has no precise direction,” and maybe hoping that everyone would take the same lessons from the past is a fool’s errand. But “The Meaning of Hitler” never quite reconciles its central concern of whether continuing to talk about Hitler is an inherently compromised pursuit, and that uneasiness feels like an unintentional capitulation for an otherwise well-intentioned project.

Now available in theaters and available for digital rental.