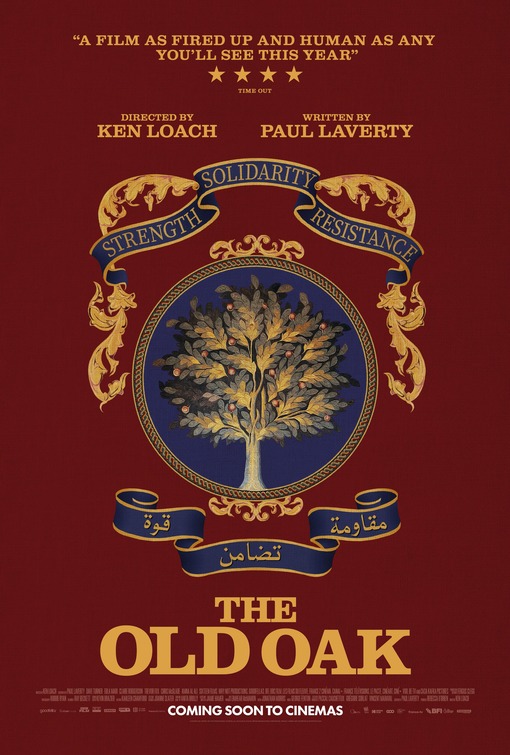

Eighty-seven-year-old filmmaker Ken Loach’s “The Old Oak” is about how changing demographics in a struggling English town called Durham manifest in a crumbling old pub, the last public space that everyone claims as their own. This is Loach’s latest and (according to Loach) final motion picture, and it feels like a summation. It’s as engrossing, thoughtful, heartfelt, angry, hopeful, and altogether valuable as his best work. If it is indeed Loach’s farewell, it’s one hell of a fine note to go out on.

There are almost always scenes in Loach’s films where a group of locals gathers in a shared space to argue about issues that affect all of them. The space here is the bar of the title, owned and operated by TJ Ballantyne (Dave Turner). TJ assists a local charity spearheaded by Laura (Claire Rodgerson) that gives donated furniture and other household items to Syrian war refugees. TJ is a goodhearted and tough but depressed man who lost his wife and son many years ago and dotes on his little dog. He has grown increasingly disenchanted with his core group of patrons, a bunch of men his age who blame immigrants for a decline in living standards that predates the newcomers’ arrival by decades. There’s even a gallery of photos in a shuttered back room of the bar commemorating local labor struggles back when TJ was a teenager and Durham was still built around coal mining.

The film begins, like many Loach movies, by dropping you into the middle of a conflict. A group of Syrians have arrived in town by bus and are being harassed by white locals (some of whom apparently aren’t even from the neighborhood; hate tourists, basically). One of the new arrivals is teenaged Yara (Ebla Mari), a budding photojournalist who shoots the old-fashioned way, on 35mm film. She documents her family’s arrival, including their harassment by the xenophobes telling them to go back to a war zone that’s already shattered their spirits (Yara’s father is missing and presumed dead). One of the bullies steals Yara’s camera and turns it on the newcomers and then, when confronted, gleefully drops it on the pavement, breaking it.

This sparks the beginning of Yara’s relationship with TJ, which forms the backbone of “The Old Oak” and unites the different story strands—and the fractured community as well. TJ invites Yara into the back room of his bar, which hasn’t been used in decades due to plumbing and electrical problems, and offers her a replacement 35mm camera from a collection that once belonged to his late uncle, who took photos of the town’s mining heyday that hang framed on the walls. The film takes its sweet time perusing those pictures and even lets TJ give Yara a tour through time and space as they look at them. We get the sense of the weight of the past (always a factor in Loach’s movies, whether the past is nostalgically fantasized and false or based on something real, which is the case here) and also of the mercurial present. Thus begins a believable and quietly powerful story consisting of simply written and blocked scenes that explore the dynamics of the town.

Loach and his regular screenwriter Paul Laverty (a legend in his own right, though a comparatively unsung one) do their usual thing, which is write characters who are representative of certain “types” but feel like real people and have specific concerns or issues, then set them all loose, letting them do what they’d do if they existed, even if it means that they step on each other’s feet or angrily smash against each other. One of the many remarkable things about “The Old Oak” is how it allows us to see and feel everyone’s point of view, including the perspectives of characters who are mainly looking for human targets to direct their formless frustrations at, and are wrong on the merits.

Exhibit A is the locals who blame immigrants for a gradual economic decline that’s the fault of ruthless corporations and the post-Thatcher government, not immigrants. A couple of important early scenes feature one of the bar regulars, Charlie (Trevor Fox), grousing that local homes are being bought up cheaply by faceless foreign corporations that are looking to rent them or turn them into Air B&Bs, and that don’t even have the basic courtesy to send a human into the town to look at the properties they’re vacuuming up. Meanwhile, he and his wife scramble to pay the upkeep on their own home. They are trapped, economically unable to either stay put or sell. You get why Charlie would be furious and, in his zeal for scapegoats, would cast a wide net that pulls in not just the newcomers but the people trying to make their resettlement less painful.

It’s unreasonable on its face that anyone should be mad at TJ and Laura for bringing donated items to war refugees (they exemplify Christian values far more than the xenophobes and racists who mock newcomers for being brown and Muslim and joke about them being terrorists). But you can also see how the white citizens of Durham would resent their own kind helping newcomers while they themselves struggle through a life that’s not as dire as what the refugees are dealing with but is still nothing to joke about.

An especially piercing moment sees Yara escort a local white teenager back to her house after she collapses during an athletic event due to lack of food; Tara then goes into the girl’s family’s kitchen to find her something to eat and learns that the cupboard and fridge are almost bare. In an earlier scene, TJ and Laura give a little Syrian girl a bike while three local boys look on. TJ explains that it’s an old bike that was donated, but that doesn’t make an impression on the boys, one of whom states that he also wants a bike. Nobody in this scene is wrong. There’s just a lot that needs to be worked out, and the factors contributing to the the conflict are beyond the scope or understanding of any one person in the scene.

Loach and Laverty have a clearly defined hierarchy of values that applies to all of their collaborations. They’re socialists who believe in a collective community and government responsibility to care and uplift. They define that responsibility against the narcissistic ruthlessness of capitalism and the governments it has corrupted and captured, and tie it back to an increasingly marginalized and mocked sense of what Christian values are supposed to be about.

It’s relevant to the story that Durham was once organized around the local church, which was revered not just for its religious function but for the way the buildings themselves were physically connected to the community through the workers who built the place. The church is still operational but is an abstraction to most of the characters, including TJ, who hasn’t set foot inside it for many years. The decline of the church (which of course had its own problems) explains why The Old Oak has become such a valuable and fought-over meeting spot.

The movie named for the bar has a spiritual dimension that was often downplayed in early Loach works. This is expressed not just through arguments and monologues about the moral responsibility to help the less fortunate, but through scenes of characters getting together and doing something helpful, whether it’s bringing a mattress to a newly arrived family or staging a potluck dinner that will introduce the refugees to the locals. This reaching-out process builds new relationships that represent the economic safety net that was destroyed. But it can’t replace it, because individuals don’t have the power of governments.

Loach has always told stories that use real locations and some nonprofessional actors, encourage improvisation, and take their stories from contemporary or historical events that affect the everyday lives of working and/or struggling individuals. These are not the kinds of films where billionaires fly to Norway on a private jet to plot a corporate takeover, nor are there genre movie elements (horror, science fiction, film noir, etc). The camerawork (overseen here by Robbie Ryan) focuses on capturing moments of interaction between individuals and groups of people rather than making statements on its own. The aesthetic is as rigorous in its way as any that you see in work by filmmakers who are more ostentatiously formalist in their approach.

There are echoes of social realist or “kitchen sink realist” playwrights like John Osborne (“A Look Back in Anger”) and Arthur Miller (“All My Sons,” “Death of a Salesman”) in the scenes delving into TJ and Sora’s friendship, the pain of their pasts, and the quiet tragedy of their stories and those of all the other characters going largely unnoticed by the wider world. Several of them echo one of the signature speeches in “Death of a Salesman,” by Linda, talking about her salesman husband Willy: “Willy Loman never made a lot of money. His name was never in the paper. He’s not the finest character that ever lived. But he’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He’s not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a person.” This is an entire movie filled with Willy Lomans, some more likable than others, all worthy of attention.

The entire exercise often plays like a documentary record of actual events for which a camera happened to be present. You truly feel as if you’re getting a slice of life. Often in Loach’s films it’s a bitter slice. That’s not the case with “The Old Oak,” a drama that has many troubling or devastating moments but barrels through them, and lets the characters emerge with shreds of hope for a better future.