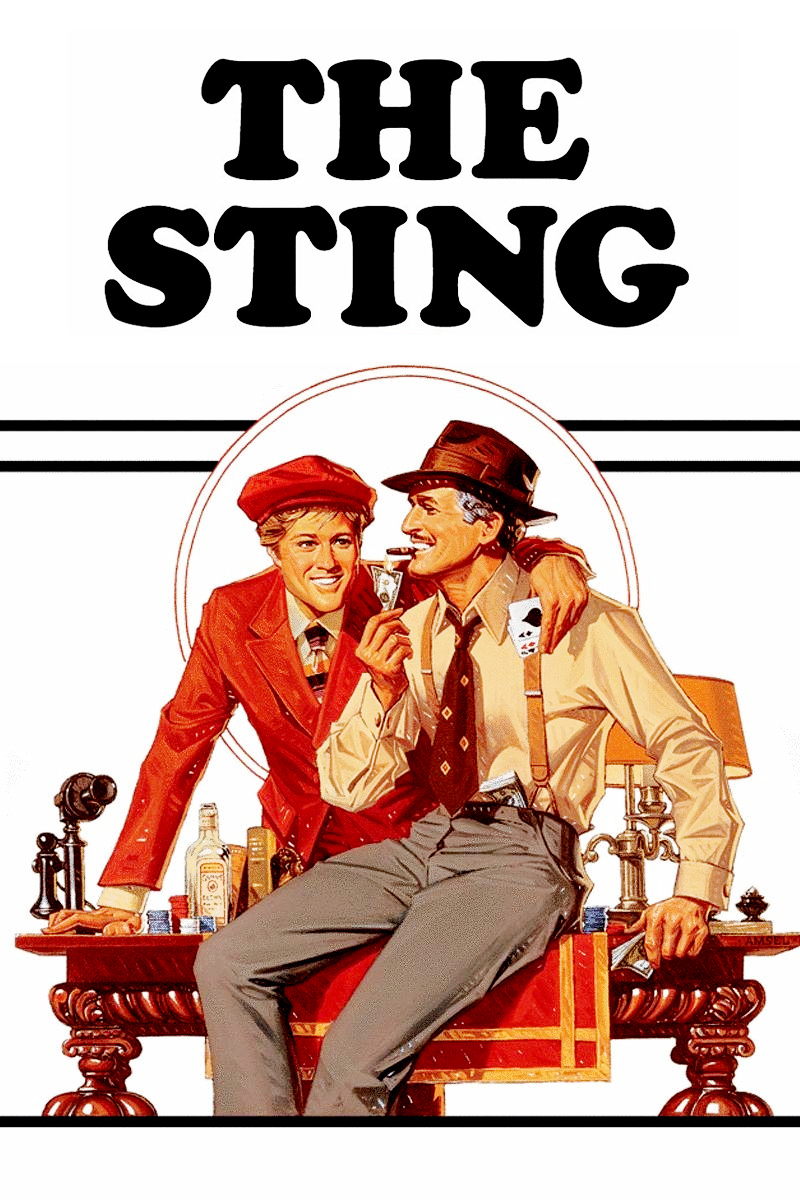

“The Sting” is one of the most stylish movies of the year. That’s an especially pleasant surprise because it reunites the co-stars and the director of “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” a movie I thought was overrated.

The director is George Roy Hill, and the stars are those two good old buddies Paul Newman and Robert Redford. This time, they play con men who methodically and with great ingenuity fleece a rich mark (Robert Shaw). Their methods are incredibly complex (it would take all of today’s space to attempt to explain them.) A lot of the fun in the movie is watching Hill and his screenwriter, David S. Ward, keep the plot straight.

The movie is set in Chicago of the 1930s, and many of the outdoor scenes were shot here (including an effective platform shot at Union Station). We see a big, confused, lusty, brawling city where the big guys with the muscle are somehow always losing to the guys with the confidence angles. Robert Shaw never figures out what hit him. Shaw is a high-stakes gambler who first gets hooked during a poker game between New York and Chicago on the 20th Century Limited. Newman and Redford spot him, mark him and begin to manipulate him. He never figures out they even know each other, and that’s part of the charm: They have to play a lot of scenes for him as complete strangers, as Redford casually lets drop that he knows the location of the biggest wire room in Chicago.

The idea, Redford explains, is to allow Shaw to win big on a fixed horse race in order to . . . but I wasn’t kidding when I said the scheme is complicated. Paul Newman operates the wire room. Or should we say it appears to be operated by Newman. Or, more accurately, it appears to be a wire room, because the entire operation is simply a theatrical set, and everybody in the room is an actor, and the “broadcasts” from the track actually are being made up by an announcer in the back room.

The movie has a nice, light-fingered style to it. Hill gently kids the 1930s with his slight exaggerations of fashions and styles. He tells his story episodically, breaking the movie down into the various plateaus of the con game. And he’s awfully good at maintaining a kind of off-balance pacing; we can never quite pin Newman and Redford down. They’re always sort of angling into scenes, making enigmatic statements under their breath and staying at least a step ahead of us. Hill’s visual style is oblique; instead of stationing his actors in the frame and recording the action, he seems to sneak up on it. Newman and Redford almost seem on their way to another movie. If that sounds like a criticism, it’s not meant as one: The style here is so seductive and witty it’s hard to pin down. It’s like nothing else I’ve seen by Hill, and at times, it almost reminds me of Jacques Tati crossed with Robert Altman. It’s good to get a crime movie more concerned with humor and character than with blood and gore; here’s one, as we say, for the whole family.