A man gets drunk and commits a senseless murder. He is condemned to death by guillotine. But in the 1850s on a small French fishing island off the coast of Newfoundland, there is no guillotine, and no executioner. The guillotine can be shipped from the French island colony of Guadeloupe. But the island will have to find its own executioner, because superstitious ships’ captains refuse to allow one on board.

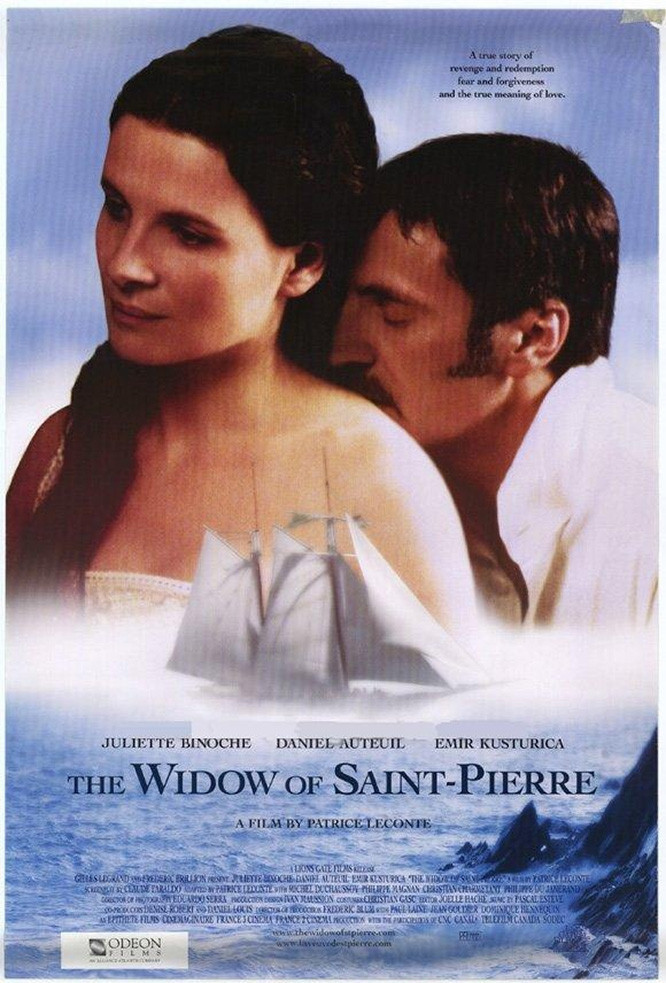

Time passes, and a strange and touching thing happens. The murderer repents and becomes a useful member of the community. He saves a woman’s life. He works in a garden started by the wife of the captain of the local military. The judge who condemned him frets, “His popularity is a nuisance.” An islander observes, “We committed a murderous brute and we’re going to top a benefactor.” “The Widow of Saint-Pierre” is a beautiful and haunting film that tells this story, and then tells another subterranean story about the seasons of a marriage. Le Capitaine (Daniel Auteuil) and his wife, referred to by everyone as Madame La (Juliette Binoche), are not only in love but in deep sympathy with each other. He understands her slightest emotional clues. “Madame La only likes desperate cases,” someone says, and indeed she seems stirred by the plight of the prisoner. Stirred and . . . something else.

The film is too intelligent and subtle to make obvious what the woman herself hardly suspects, but if we watch and listen closely, we realize she is stirred in a sensual way by the prospect of a prisoner who has been condemned to die. Le Capitaine understands this and, because his wife is admirable and he loves her, he sympathizes with it.

The movie becomes not simply a drama about capital punishment, but a story about human psychology. Some audience members may not connect directly with the buried levels of obsession and attraction, but they’ll sense them–sense something that makes the movie deeper and sadder than the plot alone can account for. Juliette Binoche, that wonderful actress, is the carrier of this subtlety, and the whole film resides in her face. Sad that most of those who saw her in “Chocolat” will never see, in this film, how much more she is capable of.

“The Widow of Saint-Pierre” is a title that carries extra weight. The French called a guillotine a “widow,” and by the end of the film, it has created two widows. And it has made a sympathetic character of the murderer, named Neel and played by the dark, burly Yugoslavian director Emir Kusturica. It accomplishes this not by soppy liberal piety, but by leading us to the same sort of empathy the islanders feel. Neel and a friend got drunk and murdered a man for no reason and can hardly remember it. The friend is dead. Neel is prepared to die, but it becomes clear that death would redress nothing and solve nothing–and that Neel has changed so fundamentally that a different man would be going to the guillotine.

The director is Patrice Leconte, whose films unfailingly move me, and often (but not this time) make me smile. He is obsessed with obsession. He first fascinated me with “Monsieur Hire” (1990), based on a Georges Simenon story about a little man who begins to spy on a beautiful woman whose window faces his. She knows he is looking and plays her own game, until everything goes wrong. Then there was “The Hairdresser's Husband” (1992), about a man obsessed with hair and the women who cut it. Then “Ridicule” (1996), about a provincial landowner in the reign of Louis XVI, who wants to promote a drainage scheme at court and finds the king will only favor those who make him laugh. Then “Girl on the Bridge” (1999), about a knife thrower who recruits suicidal girls as targets for his act–because what do they have to lose? “The Widow of Saint-Pierre” is unlike these others in tone. It is darker, angrier. And yet Leconte loves the humor of paradox, and some of it slips through, as in a scene where Madame La supplies Neel with a boat and advises him to escape to Newfoundland. He escapes, but returns, because he doesn’t want to get anyone into trouble. When the guillotine finally arrives, he helps bring it ashore, because he doesn’t want to cause work for others on his account. He impregnates a local woman and is allowed to marry, and the islanders develop an affection for him and begin to see the judge as an alien troublemaker from a France they believe “doesn’t care about our cod island.” Now watch closely during the scene where Neel marries his pregnant bride. Madame La hides it well during the ceremony, but is distraught. “It’s all right; I’m here,” Le Capitaine tells her. What’s all right? I think she loves Neel. It’s not that she wants to be his lover; in the 1850s such a thought would probably not occur. It’s that she is happy for him, and is marrying him and having his child vicariously. And Le Capitaine knows that, and loves her the more for it.

The movie is not even primarily about Neel, his crime, his sentence and the difficulty of bringing about his death. That is the subplot. It is really about the captain and his wife. About two people with good hearts who live in an innocent, less self-aware time, and how the morality of the case and their deeper feelings about Neel all get mixed up together. Eventually Le Capitaine takes a stand, and everyone thinks it is based on politics and ethics, but if we have been paying attention we know better. It is based on his love for his wife, and the ethics are an afterthought.