Every film lover of my generation has a story about how they first encountered “Siskel & Ebert,” the game-changing film review program that brought together competing journalists, Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune and our site’s namesake, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, to discuss the week’s new releases. As a child mesmerized by visual storytelling, I was an avid viewer of their program long before I was gifted at age 12 my copy of Ebert’s 1998 Video Companion, which I read so frequently that the cover fell off. Siskel’s death from a brain tumor in 1999 devastated me, and when Ebert passed in 2013 after a long battle with cancer, I was at the very front of the line to attend his public funeral. Little did I know that only a year later, I would have the honor of being hired by Roger’s widow, Chaz Ebert, to join the editorial team of this site, for which she serves as its indispensable publisher.

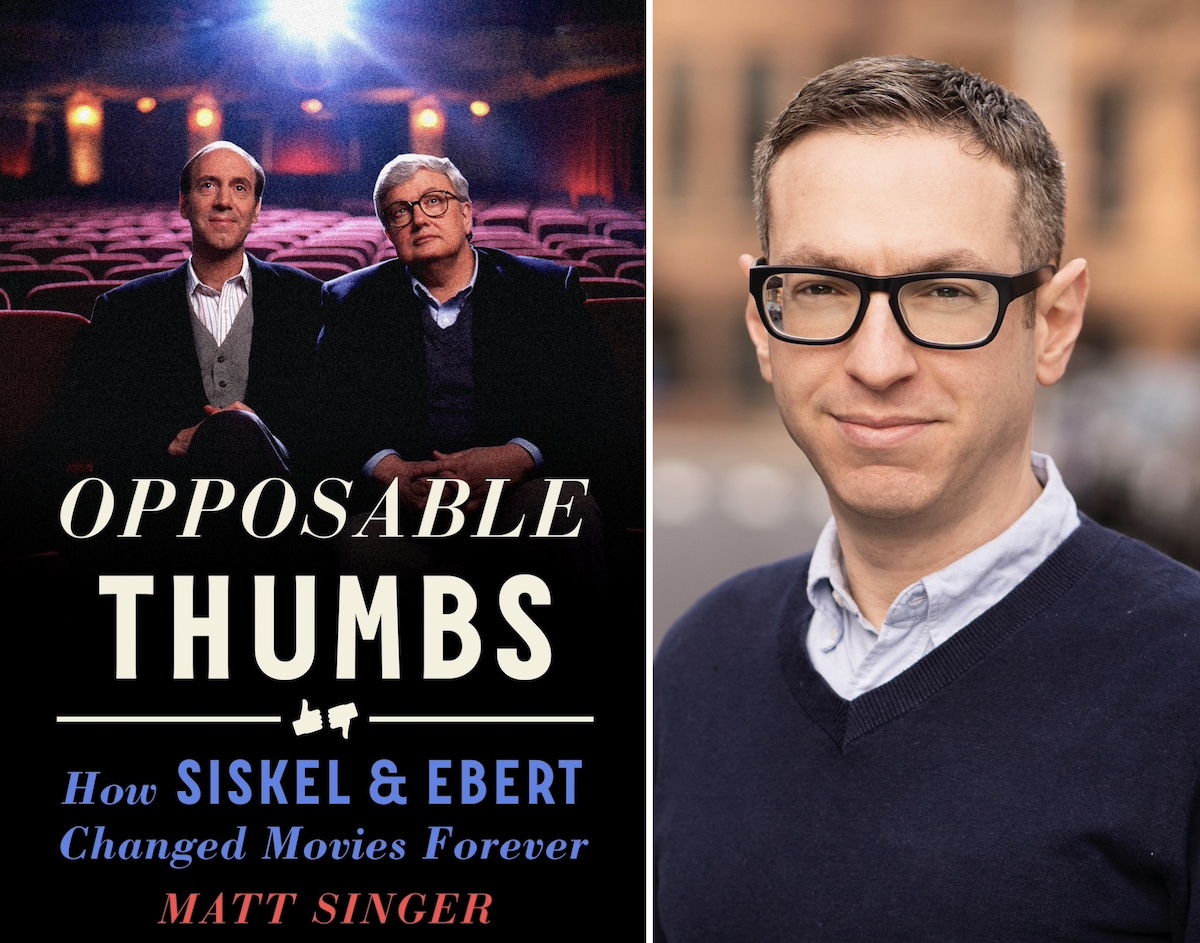

So obviously, I am among the target audience for author Matt Singer’s wonderful new book, Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever. Not only is it guaranteed to captivate long time devotees of the show, it takes such an entertaining and engrossing deep dive into the history and tremendous influence of its topic that even readers who haven’t viewed a single episode will be hooked. I had the pleasure of speaking with Singer at length via Zoom about the book, which will be available to purchase next Tuesday, October 24th.

I’ve been an admirer of your work going back to the early IFC days, when the channel actually had IF (Independent Film) on it. What was your experience like as a contributor on “Ebert Presents: At the Movies”?

It was amazing because, as you can tell from the book, I was a huge “Siskel & Ebert” fan growing up, especially when I got into college and grad school, which was in the late 90s and early 2000s. I was also a big fan of Roger’s writing, so getting to work with him on that show really was one of those “pinch me” moments. I remember doing three segments for the show, and I would basically send in ideas for them. I submitted the scripts, and Chaz and Roger would give me feedback. Once they approved it, they were like, “Go for it,” and I got to have a lot of freedom to do these in the way that I wanted.

For my segment on Brian De Palma’s “Blow Out,” I got to play with sound. I also shot, on an iPhone, a segment that was about a film shot on an iPhone, which at the time was almost as novel as making a whole movie on it. Nowadays, it would not be impressive at all. I really loved the segment I did on David Cronenberg’s “Videodrome” because we got very elaborate with it. The person who shot and edited the segment was able to put me on a VHS tape that enabled me to interact with myself on an old tube television. I wish that the show had continued. I would’ve loved to have done 100 of those segments.

What was it specifically about Roger’s writing that had an impact on you?

He had this wonderful ability to write eloquently and beautifully about sometimes very esoteric movies in a way that was so approachable. Nothing seemed obtuse in his hands. When it filtered through his mind and came out his fingers when he wrote, he made every movie sound interesting—at least the good ones. Obviously, he can’t make “The Adventures of Pluto Nash” into a masterpiece, but I loved reading his reviews of bad movies too, which were wonderful and witty. The first book of his that I loved was I Hated Hated Hated This Movie. I read that book cover to cover and back to front.

You could tell that even his most negative reviews—such as “Mr. Magoo,” which I loved so much that I memorized it—were fueled by his love of cinema rather than condescension.

Exactly, his negative reviews often came from a place of disappointment. Then when I was a little older, I got into the Great Movies books, and I now have a whole Ebert shelf in my house. If you had already seen the movie that he was reviewing, he would help you reach a deeper understanding of it, and if you hadn’t seen the film, he’d make you want to explore it for yourself. Yet he was such a great writer that it almost didn’t even matter what movie he was writing about and whether or not I wanted to see it. I just enjoyed reading whatever he had written, and I’ve always aspired to that level of intelligence but approachability in my own writing.

I really appreciated how this book is evenly balanced between telling Gene and Roger’s stories.

That absolutely was an intention of mine and I’m glad to hear that you felt it was balanced. There were a few different origins of the book that all kind of intersected. One is that between the ages of 13 and 25, I was essentially researching for the book. Any sort of writing or film criticism I’ve done can be traced back to my love of their work, and I felt at a certain point that a book should be written about them together. Roger obviously wrote a wonderful memoir, Life Itself, but there hadn’t yet been a book specifically about “Siskel & Ebert.” Only three chapters in Life Itself are about the show, so I figured there was still enough meat on the bone for me to explore. I felt there should be a book about the show and its impact that contained all the hilarious and fascinating behind the scenes stories. I wanted to read that book, so I eventually decided to write it.

At the same time, because I am such a huge fan of the show, it was intimidating. I had written a couple of books before, and I was fishing around for the next thing to do. I had a list of potential topics that I showed to my wife, and she said, “Some of these things would work, but why isn’t ‘Siskel & Ebert’ on here?” I hadn’t put it on the list because I was worried that I would screw it up. It meant so much to me that if I did a bad job, it would really eat at my soul. My wife was like, “First of all, you’re neurotic. Get over yourself.” [laughs] And that’s why I love her. Then she said, “If anyone else writes this book and you don’t, you’ll be furious!”, and I was like, “You know what? You’re right.” So all those sorts of factors came together, and that is what got the ball rolling down the hill.

How did you go about structuring the book?

In order to get my publisher, Putnam, onboard, I had to make a pitch document that included an outline. Because I was very fortunate to have worked a little bit on the final version of “At the Movies,” I had gotten to meet people like David Plummer, who was a supervising producer on “Ebert & Roeper,” and Don DuPree, who directed “Siskel & Ebert.” I reached out to them and said, “Just tell me stories.” Once they realized that I had no ulterior motive and that I just loved learning more about the show, they enjoyed telling them to me. Yet I wasn’t interested in simply writing a dishy biography. Part of what I loved about Roger and Gene was how they instilled their love of film in me, and I really wanted that to be a big part of the book as well. Throughout the book, I tried to alternate what sort of stories you’d be getting, such as their talk show appearances, the filmmakers that they helped inspire and all the drama that occurred when they went to Disney.

I also wanted to examine how they approached writing their reviews. In fact, one of the few things in the book that I didn’t include in the original pitch was the Appendix. That was something that I found during the research where I was rewatching hundreds of episodes of the show. I was struck by how many moves they really enjoyed that I wasn’t all that familiar with. I thought it would be great to get a little flavor of the Ebert Video Companion in there, as well as the “Siskel & Ebert” episodes that would highlight obscure titles that they dubbed “buried treasures.” So for the Appendix, I selected twenty-five lesser-known films that Roger and Gene recommended, and I watched each of them myself to ensure they had my stamp of approval as well. If people tell me that they sought out a film that they read about in the Appendix, that would be one of the best compliments that I could possibly get about the book.

The Appendix is a masterstroke in how it honors what Gene and Roger did in passionately championing work that they believed in. I was especially happy to see Nancy Savoca’s “Household Saints” on there, which I struggled to find online after watching its rave review on “Siskel & Ebert” [you can view it at the 12:04 mark in the video embedded above].

I like all of the films that are in there, but if I had to rank them, “Household Saints” was honestly among my two or three favorites that I felt were magnificent movies that deserved to be famous classics. It actually just had a rare revival screening at the New York Film Festival, while another film in the Appendix, Michael Roemer’s “The Plot Against Harry,” was shown this summer in a new 35mm print at Film Forum, so hopefully some of these movies will get to be rediscovered by audiences.

Tell me a bit about the rare footage you found in the archive at Chicago’s Museum of Broadcast Communications.

The footage I found there was of a dinner entitled, “Siskel & Ebert: A Critical Revolution on Television,” that occurred at the museum on April 16th, 1998. You had to pay for a table because it was a fundraiser, and the museum’s archivist, Valerie Kyriakopoulos, was able to digitize and send me the full 90-minute tape, which to the best of my knowledge has never aired. I figured they just filmed it for the posterity of the museum. I ended up quoting from it quite a bit in the book because it was filmed right before Gene got sick, and they told some stories that I hadn’t heard before. The way that they talked to each other was at times kind of touching, particularly at the end, when they were actually nice to each other and said how much they mean to each other. That was a real find.

Was there any other footage you came across during your research that was particularly revelatory for you?

You could only imagine, as a “Siskel & Ebert” fan, what it was like for me to give myself permission to watch hundreds of hours of the show on my computer. To someone else, that might sound like a chore, but to me, it was so much fun. I would have my day job, then put the kids to bed, say goodnight to my wife—who’s a teacher so she tends to go to bed early anyway—and I would have a couple hours with Gene and Roger every night. It brought me back to being a kid and discovering movies through the show. There were many reviews that I either hadn’t seen or had forgotten about. One chapter in the book begins by talking about a particular episode where they review two 1990 melodramas, John Erman’s “Stella” and Paul Brickman’s “Men Don’t Leave.” Gene says on camera, “This is the episode of the show that we need to preserve,” almost as if they’re making a time capsule.

Those movies are certainly not remembered today, and so if you were ranking the ten most famous “Siskel & Ebert” reviews, that would certainly not make the cut, but those are the kind of moments you remember because they’re discussing these movies in such heated terms. Just to see the way that they would go back and forth was thrilling. It’s almost as if they were boxers staking out positions, but instead of fighting, they were using their words. Another type of episode that was wonderful for me to discover were the annual Holiday Gift Guides, where they would recommend holiday gifts such as movies or technology. Every few years, something goes viral from “Siskel & Ebert,” and I’m just waiting for the moment when people discover the clip of Gene and Roger recommending and trying a home karaoke machine [watch it at the 40:26 mark here].

Now, perhaps I’m biased because I love karaoke, but to me, this is a segment that is just crying out to be discovered and go viral. There’s a bunch of those types of moments, such as Gene and Roger playing a boxing video game that is sort of a proto version of the Wii with sensory controls. I was sitting there watching these segments with my jaw on the floor. I did as best I could to watch the show chronologically and it was always exciting for me to discover what would happen in each episode. Are they going to have an interview with Madonna or Eddie Murphy? Are they going to have a viewer segment? Is it going to be a whole episode about the morality and ethics of slasher movies? If you are interested in the show, you can go down some amazing rabbit holes on YouTube, and if I inspire readers to do that as well, then I’ve done my job.

My personal favorite Holiday Gift Guide segment that I stumbled upon on YouTube is Gene’s scathing review of a 1987 animated video entitled “Lady Lovely Locks,” which superimposes the image of the viewer into the cartoon [you can view it at the 39:06 mark in the video embedded above].

[laughs] I love that clip, and here’s what is great about it. When daytime talk shows have a gift guide segment, it is always positive. If Gene and Roger liked a product, they would encourage you to buy it, but they would also let you know if it was a piece of junk. That may not have been what the people providing these products wanted, but these two guys were unwilling to make a homogenized, happy-go-lucky gift guide because they always were, to the very end, honest journalists.

Even on a show where they were ostensibly there to promote products for the holiday season, they made sure that they were recommending things that they really felt were worthwhile and they would actually try all of these things out. If the product was a video camera, they would take it home, shoot a home movie with it and then show it on the program so that you, the viewer, could decide whether it was worth the money. It was refreshing for me to see how they approached these specials with the same rigor as they did their jobs as film critics.

What would you say distinguished Gene as a critic?

I wish that there was a GeneSiskel.com just as there is a RogerEbert.com that serves in part as a definitive archive of his work, though if you go on the Chicago Tribune’s website, you can find some of his stuff on there. What I really walked away from the whole process admiring so much about Gene was, again, the honesty and the incorruptibility that he brought to his job. He never said anything to make someone happy or appease someone else, and that was true in both his reviews and interviews. There was a period in the early to mid 90s where they decided to occasionally add some interviews with celebrities and filmmakers to the show in place of the home video segments. When I worked in television, I would go to TV junkets all the time where I’d sit in a hotel room and have a four-minute conversation with someone in which I’d try to get something that I could use for the segment.

Everyone in those rooms is smiling and playing nice. You watch the interviews that Gene did at these things, and they’re not puff pieces. He’s doing serious journalistic interviews in a setting where, to my knowledge, no one else has ever done them because they are afraid that if they ask the wrong question or say something mean, they will be kicked out and won’t be invited back. It’s all about access and Gene was clearly not afraid of losing his own. He would be put in rooms with these big stars, and he wasn’t awed by them. He’ll just say to Eddie Murphy, “Why aren’t you working with better directors?”, and if you watch that segment [at the 12:58 mark here], Eddie is looking around wondering, “What alternate universe am I in now?” He can’t believe that he’s being asked that question, but then he gives a good answer and they have a real conversation.

I loved that about Gene and how he brought that same energy to his reviews. He never felt that he needed to temper his criticism when reviewing a film that was widely liked. He didn’t care what the consensus was. If he loved a film, it doesn’t matter to him if a hundred other people hated it. That’s not an easy thing to be the guy who’s out on a limb, even as a film critic. I’ll be honest, I would not have the guts to ask things like, “Why is this movie struggling at the box office?”, or, “Why are you making such questionable choices?” to a huge movie star, and I respected the hell out of the fact that he would.

You beautifully hone in on moments when their discussions on film would have a profound subtext, such as when an ailing Gene discusses mortality in relation to Martin Brest’s “Meet Joe Black,” just as Roger did when reviewing Robert Altman’s “A Prairie Home Companion” in the days prior to losing his ability to speak.

Yes, and that’s another wonderful thing to remember is that there were reviews in which they would talk about things like philosophy, religion and politics. Not to be too hoity-toity about it, but you could learn a lot about life from watching “Siskel & Ebert” and listening to how they would discuss and debate these subjects. Because of this, they sometimes catch you off guard, certainly like you said with the “Meet Joe Black” review. I probably didn’t make much of it at the time because we didn’t know how sick Gene was, but when you watch it now with that in mind, it’s moving and powerful. There is an autobiographical element to all criticism, whether or not it’s acknowledged, and that idea was embedded into the show because it had two points of view.

The implicit permission that it gave the audience in general, and to me personally at a young age, was to disagree with the consensus. If someone says, “This is the best film of the year,” you don’t have to agree with them. You can give “Full Metal Jacket” thumbs down and “Benji the Hunted” thumbs up. All criticism comes from a viewpoint that is subjective, and the best film criticism speaks truthfully to what you experienced and what you think it’s about. The fact that this was a show dedicated to people having multiple points of view and not necessarily agreeing about everything was—for all the fun and fighting—very important and, in its own quiet way, kind of mind-blowing, even if I only really thought about it in hindsight.

You also insightfully cover how the show went through many different hosts following Ebert’s departure.

I felt that was an important part of the story for me to include because it was so hard to replace them and there were so many different attempts to do so. I certainly watched the show when it was “Ebert & Roeper” and it was still a good show, even though it was not “Siskel & Ebert.” It’s interesting to ponder why it is so hard to replace these guys, since the concept for their show was such a simple one. We see now that so much of television resembles “Siskel & Ebert,” but it’s not about movies, it’s about everything else. At the time, the show’s concept was a novel one because there wasn’t much actual debate and discussion on television. Now there are podcasts and YouTube videos that have the spirit of “Siskel & Ebert,” but that idea just hasn’t clicked in the same way on television, and I’m still not entirely sure why.

Maybe they just cast such a big shadow that it was hard for anyone else to continue the show because they were inevitably going to be compared to them, and it was hard to measure up. I talked to all of the people who did the show afterwards for the book, and I thought they all gave very honest and fair assessments of their performances. I thought Michael Phillips and A.O. Scott did a great job on their version of their show. It didn’t have that “Siskel & Ebert” combativeness, so if you’re watching the show to see people arguing, their “At the Movies” was not for you. But if you wanted to see two great critics talking about films, you got it. I also think Christy Lemire and Ignatiy Vishnevetsky were great together and kind of coming into their own. Yet all of these people were essentially thrown to the wolves.

It’s not like Gene and Roger showed up at WTTW, were put on the set and were immediately great on camera. Their first episodes were not good, and it took them a long time to figure it out. They were fortunate that their show was a small one on PBS and by the time they found their audience, they already had years of practice. Now imagine you’re the guys replacing them after decades, and your first episode is being syndicated on hundreds of networks around the country. That’s tough! At the time, when people were getting cast on the show, I would’ve done anything to get that job. But after talking to people like Ben Lyons and Ben Mankiewicz, the feeling that I got was, “Boy am I lucky that I didn’t get a job like that!” Can you imagine how hard it must’ve been to have that target on your back? They were given an impossible task and the things that people said about them were brutal.

In what ways would you say that Roger and Gene “changed the movies”?

It is sort of a grandiose title, I’ll grant you that. Hopefully you walk away from reading the book feeling like these guys had a huge impact in terms of changing the world of the movies and the way that we understand it, as well as the ways that people talk about, think about and discuss movies. When the show was on, it was hugely influential in the way of promoting filmmakers like Errol Morris who may not have had successful careers otherwise, a bunch of whom I spoke with for the book, and we as the audience are living in a better movie world because of it. Some of the stances they took and some of the causes they championed—not colorizing black and white movies, encouraging people to watch classics by Fellini or Godard in their home video segments—filtered down into the audience, resulting in countless people like me becoming film writers, film lovers and even filmmakers because of the show.

Ramin Bahrani talked to me about how watching the show really opened his eyes to movies beyond the stuff that would open each week at his local multiplex. Their show was the gateway because there was no internet as we understand it now, no social media, no Letterboxd, no YouTube and if IMDb did exist, it was a shell of what it is now. Sure, you had the neighborhood arts section in your newspaper as well as publications like Entertainment Weekly and Premiere Magazine, but the actual act of discovering these movies was still difficult, and this show was one of the only places where you could do that. So I do think that they absolutely changed moviegoing, moviemaking, movie-talking-about-ing, if I can invent a word. All of those things are changed forever as a result of this TV show and how these guys used their platform as a force for good in the movie universe.

Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever will be available for purchase on Tuesday, October 24th.