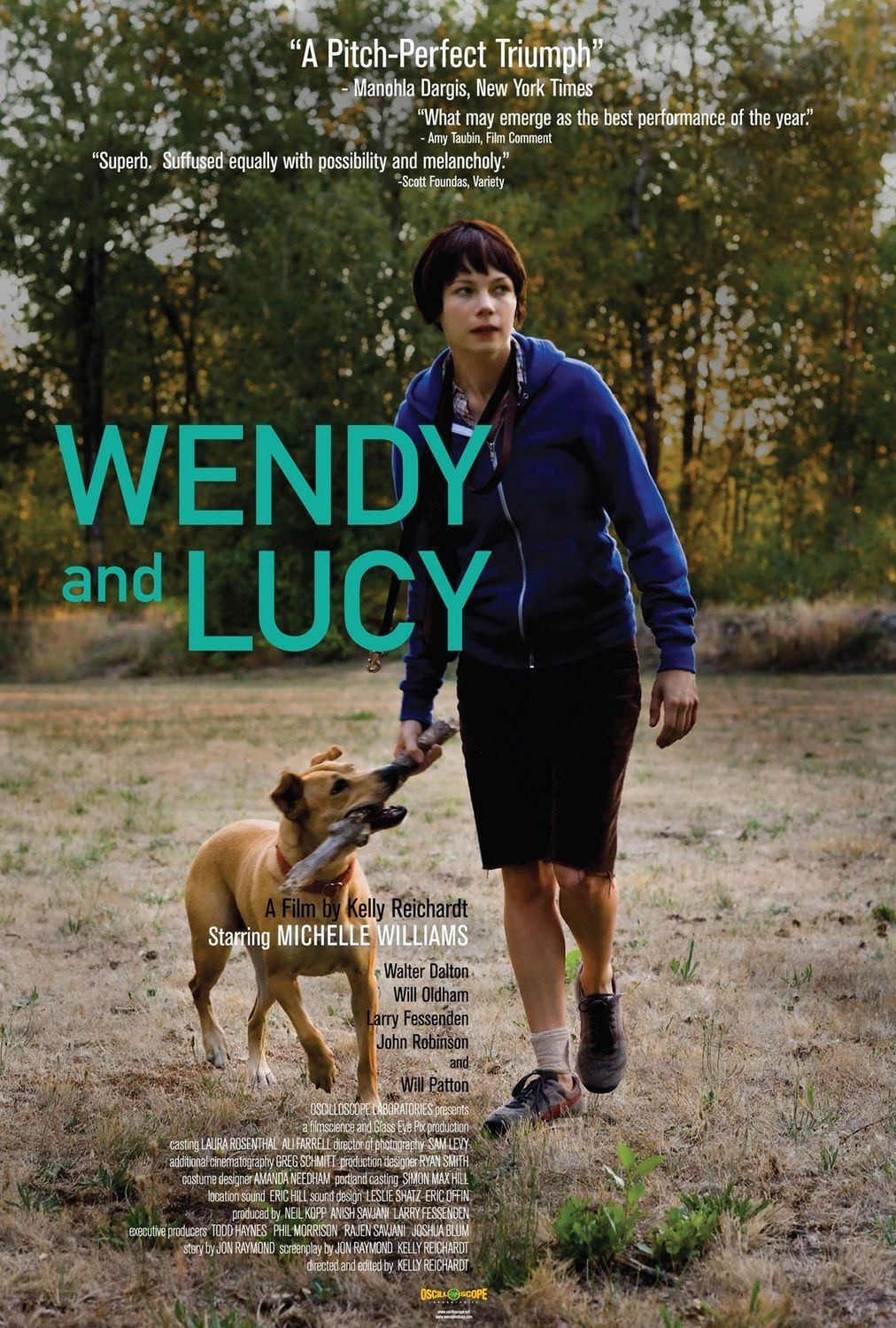

I know so much about Wendy, although this movie tells me so little. I know almost nothing about where she came from, what her life was like, how realistic she is about the world, where her ambition lies. But I know, or feel, everything about Wendy at this moment: stranded in an Oregon town, broke, her dog lost, her car a write-off, hungry, friendless, quiet, filled with desperate resolve.

Kelly Reichardt’s “Wendy and Lucy” is another illustration of how absorbing a film can be when the plot doesn’t stand between us and a character. There is no timetable here. Nowhere Wendy came from, nowhere she’s going to, no plan except to get her car fixed and feed her dog. Played by Michelle Williams, she has a gaze focused inward, on her determination. We pick up a few scraps: Her sister in Indiana is wary of her, and she thinks she might be able to find a job in a fish cannery in Ketchikan, Alaska.

But Alaska seems a long way to drive from Indiana just to get a job in a cannery, and this movie isn’t about the unemployment rate. Alaska perhaps appeals to Wendy because it is as far away she can drive where they still speak English. She parks on side streets and sleeps in her car, she has very limited cash, her golden retriever Lucy is her loving companion. She wakes up one morning somewhere in Oregon, her car won’t start and she’s out of dog food, and that begins a chain of events that leads to wandering around a place she doesn’t know for her only friend in the world.

When I say I know all about Wendy, that’s a tribute to Michelle Williams’ acting, Kelly Reichardt’s direction and the cinematography of Sam Levy. They use Williams’ expressive face, often forlorn, always hopeful, to show someone who embarked on an unplanned journey, has gone too far to turn back. And right now, she doesn’t care about anything but getting her friend back. Her world is seen as the flat everyday world of shopping malls and storefronts, rail tracks and not much traffic, skies that the weatherman calls “overcast.” You know those days when you walk around, and the weather makes you feel in your stomach that something is not right? Cinematography can make you feel like that.

She walks. She walks all the way to the dog pound and back. All the way to an auto shop and back. And back to what? She sleeps in a park. The movie isn’t about people molesting her, although she has one unpleasant encounter. Most people are nice, like a mechanic (Will Patton), and especially a security guard of retirement age (Wally Dalton) whose job is to stand and look at a mostly empty parking lot for 12 hours and guard against a nonexistent threat to its empty spaces.

Early in the film, the teenage supermarket employee (John Robinson) who busts Wendy for shoplifting won’t give her a break. He’s a little suckup who possibly wants to impress his boss with an unbending adherence to “store policy.” Store policy also probably denies him health benefits and overtime, and if he takes a good look at Wendy, he may be seeing himself, minus the uniform with the logo and the nametag on it.

The people in the film haven’t dropped out of life; they’ve been dropped by life. It has no real use for them, and not much interest. They’re on hold. At least searching for your lost dog is a consuming passion; it gives Wendy a purpose and the hope of joy at the end. That’s what this movie has to observe, and it’s more than enough.