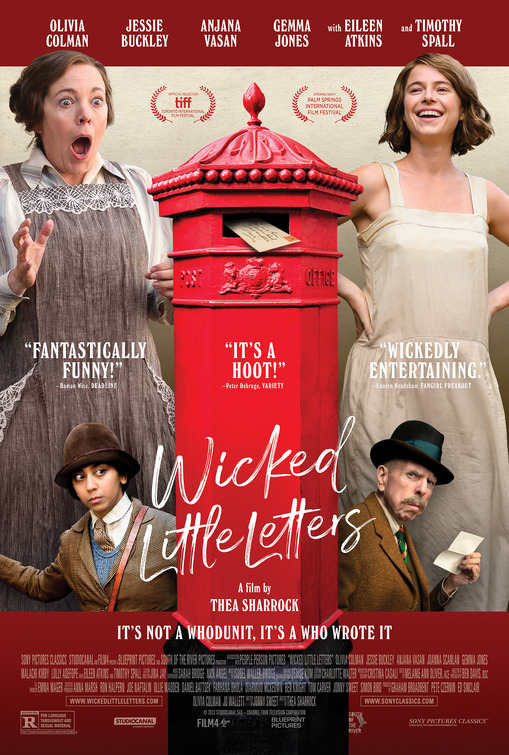

“Wicked Little Letters,” a new film directed by Thea Sharrock with a very funny script by Jonny Sweet, is based on a tempest-in-a-teapot news story from 1918-1920, a local scandal which made national headlines in England. Rose Gooding, an Irish woman with a small daughter, moved to the small seaside community of Littlehampton, and struck up a friendship with her next-door neighbor, Edith Swan, a middle-aged woman living with her parents. Soon, Edith began receiving anonymous letters, filled with obscene language, calling her all sorts of horrible names. For reasons unknown (although the film makes some very astute guesses), Edith accused Rose. Rose was Irish, with a mysteriously absent husband, and so the community was only too eager to believe Edith. There was a trial, and Rose ended up doing multiple jail stints, one involving hard labor. But then a female police officer (the only one in Littlehampton at the time) started her own investigation. She had doubts. Rose was eventually released, cleared of all charges. Such a story, with all its gossip and intrigue, silliness and absurdities, could only be a true one.

Olivia Colman plays Edith, a woman still cowering under the control of her parents (Timothy Spall and Gemma Jones). They are Christian, although they don’t seem very happy about it. Poor Edith is forced to write Bible verses over and over when she does something her father doesn’t like. Everything changes when the wild free-spirited Rose (Jessie Buckley) moves next door. Rose’s husband died in the recently ended war, and she now has a Black live-in boyfriend (Malachi Kirby), and a young daughter (Alisha Weir). Rose does not hang her head in shame. On the contrary. She swears like a sailor, drinks with men in the pub, and has sex loud enough for the neighbors (i.e. Edith) to hear. The anti-Irish feeling is everywhere in the film. The Easter Rising was just a couple years prior, and Rose fits the negative Irish stereotypes (you’ll notice the townspeople conveniently ignore that Rose fits the positive stereotypes as well). Edith is shocked by Rose, but you can see her being thrilled, too. What would it be like to just … not give a damn?

“Wicked Little Letters” starts with Edith’s accusation, and she provides the police (and us) the backstory during her interview. The police are bumbling fools, mostly, except for the young police woman, Gladys Moss (Anjana Vasan), forced to work the front desk like a secretary. Gladys’ father was a cop, and she wants to do a good job, but she is condescended to by everyone, and told by a fellow police officer to remember that her job includes “no sleuthing, love.” At some point early on in the investigation, Gladys (who was, indeed, a real person, the first female police officer in Sussex) gets the sense that something is not quite right here. Rose proclaims she didn’t do it. Gladys isn’t so sure she did either.

The first half of the film establishes the story and is fast-paced enough to hold interest, although the police interview setup is a cliched entry point. The overall tone is one of light-hearted eccentricity, and yet it’s flexible enough to allow for real sentiment. You like Rose. You feel sorry for Edith. Who would want to live with those Victorian-daguerreotype parents? But it’s in the second half, when Gladys launches her own private investigation, even after she’s been sacked for insubordination, where the film really lifts off. Gladys’ plan to prove Rose’s innocence, and hopefully catch the real culprit in the act, requires creativity and cunning, as well as a couple of makeshift stakeouts with unlikely allies. “Wicked Little Letters” is a really effective British mystery, spiked with the comedy of a real caper, with sneaky people bicycling down lanes, or literally crouching in the bushes staring at a mailbox.

Olivia Colman and Jessie Buckley played older and younger versions of the same character in Maggie Gyllenhaal’s “The Lost Daughter,” and both were nominated for Academy awards. Now they get to play opposite one another, and it’s a very pleasing pairing. They’re both so open, but in different ways. Buckley is transparent. With Rose, what you see is what you get. Her emotions- sadness, fear, rage, joy – are accessible to her. Rose is wild but she is smart, and she is righteous in her defense of herself. Her fear of losing her child is palpable. Edith is the opposite of open, and yet Colman shows us everything, the rebellious spirit, the misery, the smugness of her Christianity, her pride at finally being the center of attention, of getting all the “oh you poor thing” pity. Balancing this—the public face and the inner truth is the realm comedic actresses enter with ease, people like Catherine O'Hara, Madeline Kahn, Kristin Wiig. Colman can be very very funny, and some of the things she does here—giving us glimpses of Edith’s roiling interior all while her face remains frozen in a Duper’s Delight smile, is reminiscent of her hilarious turn as the truly awful stepmother in “Fleabag”.

“Wicked Little Letters” starts with a title card in swoopy handwriting: “This is more true than you’d think.” It’s not at all difficult to believe this is true. There’s something very modern about the film, despite its 1920s setting. “Modern,” in this case, means “eternal”. The technology has changed but the impulses have not. Bullying campaigns waged in the comments sections of Instagram and TikTok are not at all different from harassing letters sent through the postal service. A person may be perfectly pleasant “in real life”, and when hiding behind a pseudonym they are a demon. We know this. This is our world. (If you’re at all familiar with YouTube drama then you will remember the volcanic eruption of the popular creator named Creepshow Art being revealed as something other than what she was. There are similarities between “Wicked Little Letters” and L’Affaire Creepshow Art.) The letter-writer in “Wicked Little Letters” used the technology available at the time. Were it 2024, the writer would be wreaking havoc on social media, using multiple aliases, ruining lives and reputations. It’s all a joke, until someone is actually charged with a crime they didn’t commit or is SWAT-ted for no reason by an Internet mob with a grudge.

What’s really interesting is the film’s interest in the nasty impulses behind many bullying campaigns, the pettiness, the sheer silliness and what-is-the-point-ness of it all. It’s impossible to avoid the feeling that the finger was pointed at Rose Gooding because she committed the unforgivable sin of enjoying her life. How dare she?