“Zack Snyder’s Justice League” runs four hours and two minutes. That’s 242 minutes. That’s longer than “Avatar,” “The Avengers: Endgame,” “The Irishman,” “Dances with Wolves,” “Malcolm X,” “Lawrence of Arabia” and any of the “Godfather” movies. If it were released to big screens, it would tie Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 adaptation of “Hamlet” as the longest major studio theatrical release in history.

And reader, if it ever does get released to theaters, I’ll go see it again, as long as it’s in IMAX and there’s an intermission.

Some other time, perhaps, we can talk about the road that led to this moment, along with its implications for the major studio relationships to the more entitled or belligerent elements in fandom. My own feelings are summed up in the Clickhole headline, “The worst person you know just made a great point.” Bottom line: I don’t see how it’s possible to put this version of the project next to the 2017 version and not recognize that it’s superior in every way.

This four-hour cut is the kind of brazen auteurist vision that Martin Scorsese was calling for when he complained (rightly) that most modern superhero movies don’t resemble cinema as he’s understood and valued it. With its spread-out ensemble storytelling, its blend of poker-faced earnestness and grandiose tragedy, its fractured structure, and its often-glacial pacing — which marinates in moments at length, often for beauty’s sake alone, displaying a serene faith in its own judgement rarely encountered outside of so-called “slow cinema” films — this cut makes demands on the audience that have never been made by a superhero picture produced at this budget level.

The backstory: “Justice League” was meant to be the third in a series of Zack Snyder superhero films after “Man of Steel” and “Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice,” but Snyder and his chief collaborator and wife, executive producer Deborah Snyder, stepped down during postproduction to grieve for their daughter, who had died unexpectedly. The releasing studio, Warner Bros., was already pressuring the Snyders to add humor, following the relative box-office disappointment of the figuratively and literally funereal “Batman v. Superman,” which ended with Superman’s death. Joss Whedon (writer/director of the first two “Avengers” films) was brought in to take the project over the finish line, contain the running time to two hours, and keep things light. Whedon ended up rewriting and reshooting most of the movie, Whedon-izing it with smart-alecky one-liners and shooting new action scenes that, while competent, lacked the turbocharged delirium Snyder is known for. According to some behind-the-scenes accounts, less than 20% of what ended up in the final release was directed by Snyder.

The recut—it feels more correct to call it a “restoration”—contains zero Whedon footage. It’s broken into seven chapters with titles, each of which has a self-contained quality reminiscent of issues of a monthly comic (as well as old-fashioned episodic television; the Snyder Cut is as much of a medium-blurring, “Is it TV or is it a movie?” project as “WandaVision,” “Small Axe,” and season three of “Twin Peaks”). Only a sliver of what’s onscreen is wholly new, notably a forward-looking “teaser” conversation between Batman and the Joker, perched awkwardly at the end of an otherwise gorgeously shaped three-plus-hour experience. But Snyder generated so much material during the original shoot—much of it shelved by Warner Bros. without being properly finished by visual effects artists—that the totality still feels like a new work.

There’s no point getting deep into the weeds of a scene-by-scene comparison here, because the Snyder cult will surely cover it in 9/11 Commission detail, and because there’s no longer any compelling reason to watch the Whedon cut (which I liked more than most viewers) beyond curiosity. That incarnation was a Frankenstein-patchwork “rescue mission” meant to fulfill studio notes—one of which, “more humor,” seems redundant in retrospect: this cut has plenty of funny bits, ranging from the dry reactive glances and self-lacerating remarks of Ben Affleck’s Bruce Wayne/Batman; to the workplace anxiety of chief villain Steppenwolf (Ciarán Hinds), who is basically a razor-armored middle manager on probation with his nephew/boss, Darkseid (Ray Porter); to the Jeff Goldblum/Bill Murray-style, character-as-sportscaster commentary of Barry Allen/Flash (Ezra Miller); to the visual wit of Snyder’s direction, particularly in scenes where the Flash perceives time as slowed down, and we get to watch as he rearranges the universe item by item, like a fussy chef re-plating every meal at a banquet right before the staff wheels it out to the guests.

The vast majority of superhero blockbusters are not intended as freestanding works of creative expression. They’re meant to function as cogs in a content-producing machine that largely avoids painful or unanswerable questions, feeding disposable imagery and situations to viewers who expect to be rewarded for their brand loyalty and familiarity with comics lore by being given more and more and more of the thing they already know they like. The Snyder Cut, in comparison, is a corporate product that feels as if it sprung from a fever dream, like “Superman Returns,” Ang Lee’s “Hulk,” and such uncategorizably kooky/daring non-superhero comics adaptations as “Popeye,” “A History of Violence,” “Road to Perdition,” and “American Splendor.” Or, for that matter, non-comic book films maudit like “One from the Heart,” “Speed Racer,” “The Hudsucker Proxy,” and “Playtime.” Films like these are labors of childlike enthusiasm and obtuse obsession, qualities more common to art house and indie cinema than the major studio blockbuster. When you compare the hugeness of these productions to the stubbornly private choices of story and style, they seem perversely out-of-sync with whatever was considered “normal filmmaking” when they were first released into the world.

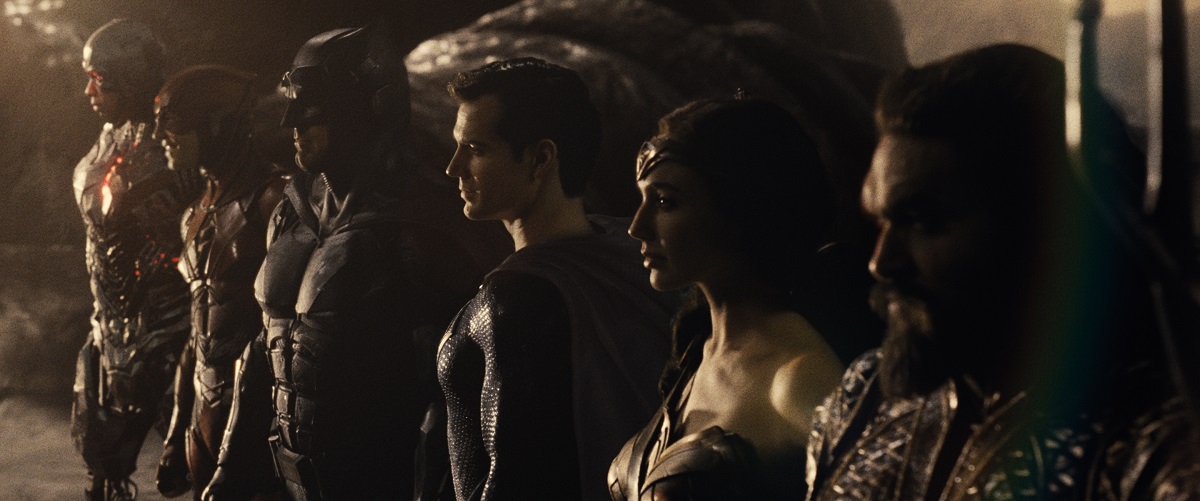

The Whedon cut of “Justice League” was the opposite of that. It felt and played more like a Marvel film, busy and quip-driven and relentlessly charming. It favored Bruce Wayne/Batman and Diana Prince/Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot) and marginalized Clark Kent/Superman (Henry Cavill), Arthur Curry/Aquaman (Jason Momoa), Barry Allen/The Flash, and Victor Stone/Cyborg (Ray Fisher). Snyder’s cut is an ensemble picture that does as good a job as MCU’s “Avengers” films of presenting a band of heroes as strong-willed, fully-rounded individuals, people who had lives and issues before the main action started, and who must learn to work to together (in service of battling Steppenwolf and Darkseid. and resurrecting Superman/Clark Kent).

Yes, there’s a plot: basically the same as in the first “Justice League,” and for that matter, the “Avengers” movies: a superhuman, megalomaniacal bad guy wants access to a source of time-and-space dominating superpowers, and can only get it by cobbling together scattered elements (six infinity stones in the MCU series, three magic boxes in this movie). But plot might be the tenth most important thing on this movie’s mind. This is the definitive cut not just in terms of canonical events and actions (“Aquaman” director James Wan and “Wonder Woman” series director Patty Jenkins are on record saying they consulted Snyder on continuity) but aesthetic purity. Some scenes have been moved and/or reshaped, others have been restructured or added, and pretty much everything has been lengthened. What registers most strongly is the film’s sense of space and place, which might make one wonder if many of the (justified) complaints about Snyder’s other superhero pictures stem from his own inclinations and the commercial demands of nine-figure-budget tentpoles being fundamentally at odds with each other.

The most remarkable restoration, character-wise, is the Cyborg storyline. It mirrors (without duplication) all the other stories of characters reconciling mixed feelings about their childhoods and accepting the limitations of their parents (or parental figures). This is the movie’s main preoccupation, and the emotion it generates becomes a binding agent for the prodution, which by nature of its audacious structure and pacing is constantly at risk of boring the audience by turning into a candy sampler of set-pieces. Fisher’s storyline—Cyborg’s resentment of his emotionally inept scientist father, played by Joe Morton, aka Skynet’s daddy in “Terminator 2″—is built out with empathy and care, and paid off in a moving climax that offers redemption without invalidating ill will.

Cyborg’s struggles complement Bruce Wayne’s relationship to his butler/surrogate dad Alfred (Jeremy Irons) as well as the memory of his murdered father and mother, absent presences that impact everything he does. Clark Kent’s relationship to his sainted adoptive mom, Martha (Diane Lane) and the departed adoptive father Jonathan Kent (Kevin Costner) and blood father Jor-El (Russell Crowe) are reconsidered, re-contextualized, and reborn along with Superman himself. Wonder Woman’s feelings about leaving her family, her island, and its culture (and their feelings about her departure) are woven in as well, plus Aquaman’s resentment at being a bi-species hybrid torn between two worlds and feeling abandoned by both; and Barry’s relationship with his incarcerated criminal dad (Billy Crudup), whom he loves and wants to please even though his actions brought shame on their family and made Barry’s life worse. (This film would feel crushingly sad if its main characters weren’t so open-hearted.)

The result is the yeastiest comics-inspired production that Snyder has made to date. The stories and characterizations genuflect towards milestones in DC comics and movies without getting cute and showing us their homework. Affleck’s greying, world-weary Batman channels the burned-out, middle-aged, Clint Eastwoodian Dark Knight from Frank Miller’s 1980s comics. The relationship between Clark Kent and Lois Lane (Amy Adams) is a “Death of Superman” riff that delves more deeply into grief than any DCEU film, and strikes idealistic romantic notes reminiscent of Superman epics from the Christopher Reeve era. It also gets into the “Monkey’s Paw” aspect of bringing a dead superhero back to life.

At this point, let’s take a moment to talk about the look of the film. “Zack Snyder’s Justice League” is framed in the squarish, roughly 4×3 “academy” ratio rather than the narrow-and-wide format preferred by most epics. This has the effect of making a new-ish work feel “old,” and it becomes as important as the parent-child thematics in terms of its ability to unify Snyder’s fragmented vision. When Junkie XL’s score is blasting and the members of the Justice League are doing heroic things rather than blabbing amongst themselves, we’re watching the superhero version of a symphonic silent epic in the vein of “Intolerance,” “Sunrise,” or “Metropolis”—scene after scene of impeccably composed panoramas, like those large-format oil paintings that depict tiny figures dwarfed by mountains and sky. Except in this case, it’s the heroes and villains who are dwarfed by landscapes and/or the cosmos—or mortals looking up in awe at superheroes looming overhead, silhouetted against sunlight, clouds, flame, and haze.

Uncharacteristically for Snyder, the camera often doesn’t move unless it needs to, and a scene doesn’t cut away until it has wrung out the last drop of whatever vibe it was trying to cultivate. Throughout, the direction seems not merely unhurried but meditative, to the point of pokiness. This is the “Satantango” of superhero flicks: an arthouse tailbone-killer. The point is not to shovel plot information at the viewer. The point is to create a fantastic world where metaphors are real, and give you time to bask in it. Scenes often start long before screenwriting manuals tell you that they should (people even take their sweet time entering and leaving) and continue way past the point when significant exposition has been conveyed. This is a feature of “Justice League,” not a bug, and even though many are bound to find it off-putting or simply boring, it results in a good number of the scenes and sequences that make the film feel truly special, even as they eliminate any possibility that “Zack Snyder’s Justice League” will tell a propulsive, coherent, orderly tale.

One such moment is an interlude in a battle between the Amazon infantry (led by Wonder Woman’s mother, Queen Hippolyta [Connie Nielsen]), and Steppenwolf and his army of winged, armored insect men (deployed by Snyder as if they were steampunk cousins of the Wicked Witch’s flying monkeys). A group of characters pause to take a long, anxious look at the water in a sea cove where a temple has collapsed, presumably crushing and drowning the enemies within. The camera fixates on the waves, watching and listening while they churn. It’s hypnotic.

Another memorable bit is more self-consciously art-for-art’s sake: Aquaman, having concluded important business in a seaside pub, walks a long pier jutting into the sea, unfazed by immense waves clashing ahead of him. The waves are powerful enough to knock over an apatosaur, but Aquaman just strolls into them, vanishing in saltwater mist. The scene is filmed in slow motion with no dialogue or sound effects and backed with a pop song cranked to 11. Christopher Nolan made a lot of noise about modeling “The Dark Knight” on Michael Mann’s “Heat,” but this is one of many moments in this film that are more Mann-like in the way that they suspend time. That Aquaman seaside power-walk is also reminiscent of the moment in “The Royal Tenenbaums” when the lovestruck Richie watches Margot walk off a bus. Except here it’s not about one character’s love for another, but the director’s love for Aquaman and the actor who plays him. `

The movie’s directorial highlight might be the sequence where Barry tries to get a job at a pet store and pauses to save a woman he’s smitten with from an oncoming truck, driven by a man who’s not paying attention to the road because he’s busy trying to pick up a sandwich he dropped. The scene feels like a self-contained short film about The Flash. It would feel that way even if it didn’t seem to promise a love story that the film is not interested in developing. The buildup to the wreck is masterful, with Spielberg-quality visuals (each time the scene cuts back to the driver going after that sandwich, it’s funnier and more appalling), and Flash’s subsequent rearrangement of reality to produce the desired outcome. Miller’s facial expressions are as perfect as the director’s choices. By any objective measure, this is a scene that could be cut for time. But in a restructured, remade movie that seems to exist entirely to showcase Snyder’s decadent and voluptuous idea of what superhero mythmaking should be, that would be like looking at a peacock and concluding that the problem was too much plumage.

“Zack Snyder’s Justice League” is so fragmented that it could’ve been titled “32 Short Films about the Justice League.” It often makes momentous promises or sets up seemingly important relationships which it then forgets. It’s so bombastic that it makes “Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice” seem modest. It will mainly please the people who clamored for it. Even fans of the genre might consider it a bit much. It owes as much to rock concerts, video games, and multimedia installations as it does to commercial narrative filmmaking. It’s maddening. It’s monumental. It’s art.

Available on HBO Max on Thursday, March 18.