Matt Fagerholm has been a gem to work with at RogerEbert.com, and I am simultaneously sad to see him go, while overjoyed for him about the project he is undertaking. This Farewell Article contains some of his best work. Onward and Upward Matt!—Chaz Ebert

It was on February 28th, 2014, that RogerEbert.com publisher Chaz Ebert gave me the green light to publicly announce that I had been hired to join her team. My initial job title was Assistant Editor at Ebert Publishing, a role designed to assist in the publication of new books compiling the work of the site’s namesake and my lifelong hero, Roger Ebert. Over the decade that followed, my duties gradually shifted toward editorial duties for the site itself, where I had the privilege of contributing reviews, interviews and various features. I covered film festivals and events in New York, Los Angeles, San Diego, Washington D.C., Indianapolis, Bend (in Oregon), Toronto, Karlovy Vary and Reykjavík, while securing a seat in the press room of the Academy Awards three years in a row.

At Ebertfest, I had the immense honor of moderating post-screening Q&As with some of my favorite people in modern cinema including Thora Birch, Derek DelGaudio, Rick Goldsmith, Kogonada, Ben Lear, Morgan Neville, Frank Oz, Rebecca Parrish, Mykelti Williamson and Terry Zwigoff. I also returned twice to the festival’s venue in Champaign, Illinois, to cover, and occasionally participate in, the sorely missed Pens to Lens Gala in which films written by students ranging from kindergarten age to twelfth grade were brought to life by local filmmakers. Throughout it all, I was fortunate enough to have the unceasing support of my fellow editors—Chaz Ebert, Publisher-in-Chief; Brian Tallerico, Matt Zoller Seitz, Nell Minow, Robert Daniels and Nick Allen—as well as the Vice President of Development of The Ebert Company, Sonia Evans, and the Project and Office Manager, Daniel Jackson, who has become like a brother to me.

Thus, on the precipice of my tenth anniversary at the site, it seems like a fitting full circle moment to bid this extraordinary chapter of my life farewell. Other projects that were birthed directly from the work I was able to publish as a result of this site are now demanding of my full attention, and I must ensure that they will cross the finish line. I am leaving at the end of this month overwhelmed with gratitude not only for every opportunity I was granted because of this site and its unequaled team, but because of everything that it has made possible for me in the years to come. Having the opportunity to champion cinematic work that I believe in on this platform has been and will forever be one of the greatest joys of my life, and I am humbled to have played a part in helping extend Roger’s legacy into the decade following his passing.

Chaz asked me about some of my favorite articles that I have published at this site, thus leading me to compile fifty from the past decade—twenty reviews, twenty interviews and ten features—that I hold especially close to my heart. Click on each article title, and you will be directed to the full piece. I want to thank Chaz for having faith in me every step of the way. I also want to thank all of my colleagues and you, our readers, for helping keep film discourse alive and well. And thank you, Roger, for your endless inspiration. I hope I did you proud.

I. REVIEWS

“A Light Beneath Their Feet” is a triumph of empathetic filmmaking. It will enthrall viewers merely seeking a coming-of-age yarn, and it contains one of the loveliest prom scenes in recent memory. But for those viewers who, like myself, can personally relate to the story and have been forced to answer the same questions, the film will bring catharsis, tears and perhaps a few epiphanies. I didn’t “get” this film so much as it “got” me.

Perhaps the film’s most singularly haunting image is that of Ye and her daughter abandoned on the side of the road, surrounded by their belongings stacked in boxes. In the last moments of the film, we learn that these boxes have been transferred in their entirety to an Ai Weiwei exhibition in New York City, where they are put on prominent display. A friend of mine once said that “a person’s very existence can serve as a protest.” Regardless of their ultimate fate, the existence of Ye Haiyan and every soul she has ever sought to protect are undeniable, and thanks to filmmakers like Wang, immortal.

This Is Everything: Gigi Gorgeous

We’ve already entered the age of Fahrenheit 451, where “friends” primarily exist on screens that take up the majority of our attention. Yet the best YouTubers are the ones who encourage their viewers to turn their attention inward and engage with the world existing outside of their laptops. When Alexis G. Zall comes out by saying she “likes girls,” or when Brad Jones opens up about surviving a suicide attempt, they aren’t just providing a diversion, they are changing lives through the empowerment of truth.

Though Donald Trump is never mentioned by name in all 140 minutes of Ai Weiwei’s new documentary, “Human Flow,” the picture is, quite simply, the most monumental cinematic middle finger aimed at his scandal-laden administration to date. In its galvanizing account of the global refugee crisis, this film is a scalding rebuke to Trump’s desired wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, his abandonment of immigrants protected under the now-defunct Dreamers program and his willful ignorance of climate change.

Consider the scene where Manana enters a family’s apartment, posing as a gas meter reader. The shot begins over her shoulder as her eyes lock with the boy who answers the door, but only gradually do we realize the child’s identity. By the scene’s end, the framing has flipped, causing us to peer over the boy’s shoulder at Manana, whose carefully modulated expression now speaks volumes. Nearly every scene is anchored by Shugliashvili’s face, which unceasingly fills in the blanks intentionally left by Ekvtimishvili’s deftly nuanced dialogue.

In a brief yet potent flashback, we see that the child Duras had with Robert turned out to be stillborn, a tragedy that may have irrevocably stunted the growth of their marriage. Some truths are best left implied, as demonstrated by a stunning moment early on when Duras welcomes her husband home, and walks to the kitchen to retrieve a drink for him. The camera continues to follow her down a hallway as her pace begins to slow, and the dream evaporates before our eyes without a single cut or line of narration.

Without ever spelling it out, Esparza shows us how our treatment of one another as members of the same human family is a direct rebuke to the divisions enforced by tyrants to keep us frightened and isolated. In its poetic simplicity, the film’s deeply moving final shot suggests that our estrangement can be mended the moment we choose to lock eyes and listen to each other, allowing our voices to rise above the deafening cries of our presumptions. Andrew’s teacher may believe he knows the family of his student, having schooled himself in their criminal records, yet the boy is entirely correct when informing him, “You don’t.”

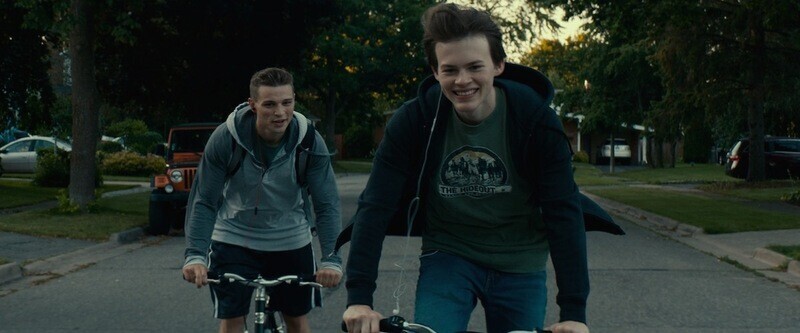

I’ll confess that I became so enamored with Behrman’s film that when it came to a perfectly pitched conclusion, cutting to black at the precise right moment, I felt like applauding. This is not a film that ends with contrived reunions and shared, meaningful nods. It acknowledges that some frayed bonds may never be mended, while arriving at a deeper level of satisfaction, enabling its hero to not only find forgiveness within his grasp, but also self-acceptance. I imagine many young people will feel an enormous weight lifted off of them after watching this movie, as the stigma limiting their own personal expression starts to dissolve. What a gift.

Bianco and her ace cinematographer Ava Berkofsky make subtly artful use of recurring motifs, most notably the lights morphing from murky blue to clear white that assist a therapist in unearthing any buried memories Mandy may have of the fateful night. The colors race across the screen, mirroring the passing streetlights she recalls from her otherwise forgotten ride home, where she ended up on the lawn. As the lights illuminate Mandy’s face, they fade back to blue, signifying her fragmented recollections that have long since eroded.

Since the premise directly evokes Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 nerve-shredding classic, “The Wages of Fear,” we find ourselves flinching along with Vlada every time we hear a suspicious noise emanating from his truck. Like Clouzot’s doomed protagonists, is he transporting nitroglycerine that could blow his vehicle into smithereens if it hits a pothole? Though Glavonić keeps the shipment a mystery for as long as possible, there are many indications early on that his film doesn’t aspire to be a remake a la William Friedkin’s 1977 “Sorcerer.” Just as a blocked bridge forces Vlada to reroute his journey, the narrative consistently veers off into unexpected territory, and the more it frustrates our expectations, the more it has us hooked. This is a film hinging not on cathartic explosions but rather, the gradual discovery of horrifying, self-implicating secrets.

Both men are now full-blown alcoholics, swerving at diagonal angles down the path of their lives while wounding passersby in the process. Yet neither Daniel nor Tillman is a cardboard villain on the order of the awful husband in “War Room,” prior to his sudden salvation courtesy of affair-disrupting food poisoning. They are the products of a system breeding toxic masculinity by dealing the Get Out of Hell Free card of forgiving-and-forgetting, brushing under the rug what should be dealt with out in the open.

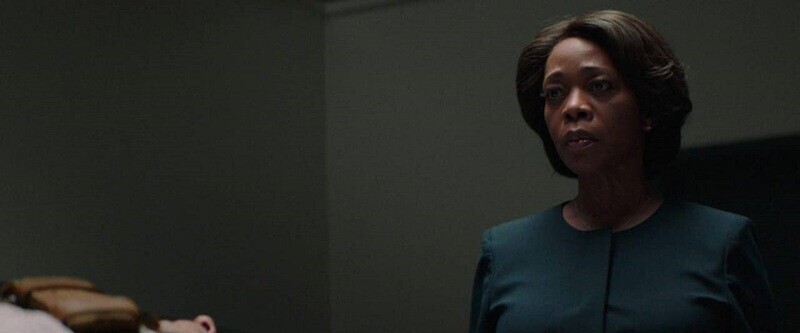

When Anthony is strapped to a crucifix-like chair and given his lethal injection, it’s as if his pain and anguish is injected directly into Bernadine. In a breathtaking three-minute shot on par with the finale of Céline Sciamma’s “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” the camera holds on Bernadine’s face as the primal horror of the procedure she has overseen for years finally sinks in, breaking through her hardened exterior until he flatlines, prompting her own body to go limp. For the first time, she finds herself at a loss for words, just as Anthony was during her feeble attempts at interaction. You can literally spot the moment when her soul appears to have left her body.

Along with his brilliant 24-year-old cinematographer, Kseniya Sereda, Balagov sports the confidence to tell his story chiefly through the faces of his characters as well as their placement in the frame, thereby making the dialogue of secondary importance. His use of long takes never calls attention to itself, while allowing his actors to engage in a subtly choreographed dance that tells us more about their relationship than words ever could. It’s crucial not to cut between emotional beats, since it is in those lingering pauses and unspoken shifts where the heart of the film lies.

By looking directly into Pearl’s eyes via the concealed camera and seeing her own disillusionment and bewilderment reflected within them, Rosa is able to free herself from the prison of unearned shame, in much the same way that Mudd felt “less stupid” after seeing Fuhrman’s performance. When the two women finally embrace, the moment is tantamount to any survivor of abuse—many of which we hear from in the film’s final moments—achieving a newfound sense of wholeness through the empowering strength of community. “Tape” isn’t just a movie. It is a rallying cry.

Beyond the Visible—Hilma af Klint

Halina Dyrschka’s debut feature, “Beyond the Visible – Hilma af Klint,” is one of the best films I’ve seen about fine art. It casts an entrancing spell that allows the staggering depth of its subject’s work to consume us, while showing how her trailblazing vision left an unmistakable imprint in over a century of iconic art spanning various mediums, resounding through history like a drop of colored paint in a pitcher of water. This is one of many metaphorical motifs Dyrschka poetically utilizes to convey the essence of af Klint’s artistry and the magnitude of its unsung influence.

The ability to read a great work of cinema is not all that different from psychoanalysis, since signs of trauma are often conveyed through nonverbal behavior rather than expositional monologues. I found myself drawing upon the same instincts I utilize for processing nuanced visual storytelling as I regarded young Sasha’s piercing stare, radiating the pent-up agony he is not yet ready to articulate. Apart from its numerous profound achievements, Neulinger’s picture is an extraordinary work of film analysis, inviting the viewer to study certain encounters frame-by-frame as a way of revealing their unspoken subtext.

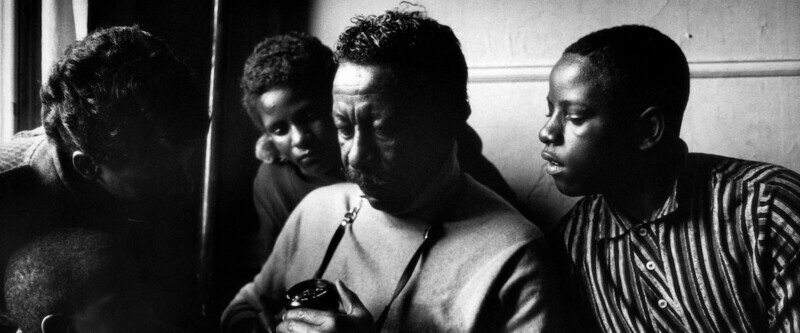

A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks

The great achievement of John Maggio’s latest HBO documentary, “A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks,” is the depth with which it delves into the nuance of indelible images such as these, which served as both vividly realized slices of life and artfully profound meditations on race. Maggio doesn’t simply gather a line-up of distinguished talking heads to inform us that Parks was important—he shows us why.

There are times in which the score by Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans swells, but never in a way that overrides the emotional truth embedded within the footage. It also knows when to preserve the sacred silence of moments where we are able to feel the weight of the family’s loss. I could write a great deal about what occurs in the film’s last half-hour, but I’d rather have you discover it for yourself. What I will say is that “Torn” elicits tears in a way that is raw, unexpected and wholly earned. By inviting viewers to share in the most private of transformative periods for his family, Max Lowe scaled the Mount Everest of the soul, creating a cinematic gift that cuts to the heart in ways few films ever do.

Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America

“Who We Are” should be made required viewing in every American school as we find ourselves perched, once again, at a pivotal tipping point. The hope found in activists of all races demonstrating together in the midst of a pandemic is underlined by the joyous gospel music over the end credits. It is Robinson’s aim to guide our eye in seeing the truth of our past that is so often overlooked. This is perhaps most indelibly expressed by the fingerprints left in walls throughout Charleston by the enslaved people who built our cities, our economy and our country, brick by brick.

Though the tendency in this streaming era is to wait for documentaries such as this to arrive on an at-home platform, Shaw’s film provides an indelible reminder of cinema’s enduring power as a communal experience. If you’re fortunate enough to see this picture on a big screen with an engaged audience, you will be reminded of why we, as a species, go to the movies in the first place: to enter the lives of others and perceive the world through their eyes until our hearts have become intertwined with their own. With fascism posing a consistent threat to the future of democracy, here is an example of grassroots activism that manages to achieve what few had thought possible, while refusing to let the cries of the people be silenced. What a glorious sight to behold.

II. INTERVIEWS

Parker Posey on “Irrational Man”

As an artist, I don’t want to compete with anyone. How can you measure one person against another? It’s very uncomfortable to go to a party and be around other actors or actresses who give you an attitude or are blatantly jealous. They don’t see the big picture and they want to compete. Art is how I make sense of my life. It’s given me a partner—the relationship to the material and to my life and how my life feeds into my art and the story. There’s a richness there, and it’s why you keep doing it.

Greta Gerwig on “Mistress America”

I like her flashes of a healthy ego. Every time I hear that line, “If I could get my look right, I’d be the most beautiful woman in the world,” it totally charms me because oftentimes female characters, particularly younger, ingénue-types, are somehow unaware of their own beauty or appeal. They’ll be like, “Huh? Am I beautiful?”, and I’m like, “You f—king know that you’re beautiful!” I love that Tracy knows that she’s beautiful, even if she hasn’t figured out what to do with it yet.

Gordon Quinn on the fiftieth anniversary of Kartemquin Films

I don’t think we, as filmmakers, are ever objective. You point the camera one way rather than another way and you’ve created a point of view. If you’re filming a demonstration and you’re standing behind the police lines, that is a point of view. If you’re standing with the demonstrators, you’ve got a different view of what you’re seeing. I don’t think any of us really claim to be objective. The point is that you want to get the different sides of the story and you want to be fair to people.

Werner Herzog on “Into the Inferno”

That’s a very good and unexpected example you have brought up. It has always been my aim to find that sort of passion and figure out how to transform it into cinema. Treadwell’s footage was almost like a diary, and he had always dreamt of becoming the movie star in his own gigantic production. He rightfully did that because he was, in a way, a star and somebody who brought us footage that nobody else has ever captured and never will again. That spirit of immersion and curiosity and awe and participation is something which Treadwell and I have in common, Clive and I have in common, and Roger Ebert had in common with us as well.

With the threat of the world becoming so misogynistic, I think it’s important to show women like this who avoid man’s weaknesses as much as possible. The men that Michèle encounters are mediocre or fragile or failures. In a way, the film takes place in a post-male era where men have faded into something that is very difficult for women to connect with.

Paul Schrader on “Dog Eat Dog”

Slow cinema isn’t really religious, it is more meditative and contemplative. I don’t know exactly how slow my film is going to be. There’s a whole buffet of slow techniques, and different directors select different items from the buffet. A Béla Tarr film is not the same as a Dietrich Brüggemann film. I’m now trying to figure out where my appreciation of slow cinema and my gut talent meet, so it can be my film, not just an imitation of somebody else’s film. There was a quote in my book from a Dutch theologian who said that art and religion are parallel lines which meet in infinity and resolve in God.

Frank Oz on “Muppet Guys Talking”

We’re fortunate to have had so many fans around the world for so long. It’s almost like the Muppets are a Trojan horse in the way that we want everyone to have fun with them, but inside, there’s something deeper. Without being didactic or saying some message, Victoria wants the film to champion the feeling of inclusion, of collaboration, of empathy and all those things that are hard to come by these days.

John Travolta on “The People vs. O.J. Simpson”

When you deal with Shapiro, you’re not just dealing with a lawyer, you’re dealing with the royal lawyer, and that comes across in his affected voice and demeanor. He used those characteristics in the way that an actor would use them. Those bits of behavior are tools that invite the audience to get very comfortable with my characters. Look at Vincent Vega in “Pulp Fiction.” So much of what one enjoyed about that character was watching how he behaved. [in Vega voice] His speech was slower, his shoulders were slumped when he ate, he rolled his cigarette and lit it in a certain way, and it looked as if he were sauntering through mud to get to a door.

Thomasin McKenzie on “Leave No Trace”

I played the young Louise, and there were some really intense and scary scenes that I had to do. That experience made me realize how, through acting, I have an opportunity to make a difference. I realized that acting was what I wanted to do, not because of the fame side of it, but because of the reward at the end of knowing that you put a really important story out into the world. Of course, I’m a teenager and that whole stardom idea is tempting and exciting, but it’s not what acting is about. I love the sort of naturalistic acting where you are being really true to the character. That’s how you connect with people and make them feel like they can relate to the story.

Laurent Bouzereau on “Five Came Back”

Every time I watch a movie, I take notes about things like framing and composition and sound effects. Hitchcock’s work represents the purest form of filmmaking because when he started directing, the movies were barely born, so everything that he created was experimental. Throughout his entire career, he continuously shows what an experimental director he is, even in commercial successes like “Psycho” or “North by Northwest.” He pushed the envelope even further in “The Birds” and then “Marnie,” which is a completely misunderstood masterpiece. You could do a whole anthropological study of his work because it has so many layers.

Dave Goelz on “The Muppet Movie”

It was a very healing place to work because it enabled you to work out your own feelings. All artists speak for us, and that applies to any kind of art, whether it’s dance or painting, anything. These people are out there saying things that they are compelled to say, working out their own issues through their own material. We all have issues that are universal, so when we recognize—even unconsciously—our own issues being expressed by an artist, we find ourselves a little purged, a little relieved that our issue has gotten out there, and a lot of times, we’re not even aware of it. I think that’s what’s going on. It’s certainly what was going on for me when I was doing the work. It was allowing me the chance to express my issues, and I think that resonates with the audience in our case because there is an underpinning of philosophy in our work. People respond to it often without knowing why.

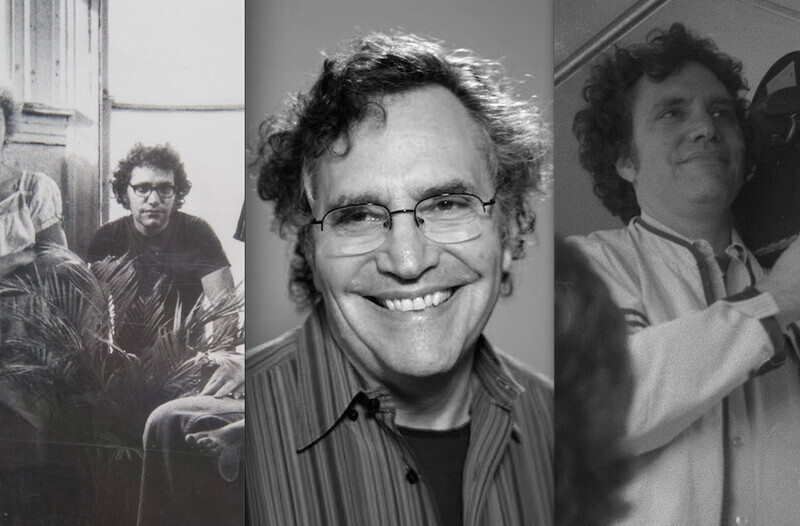

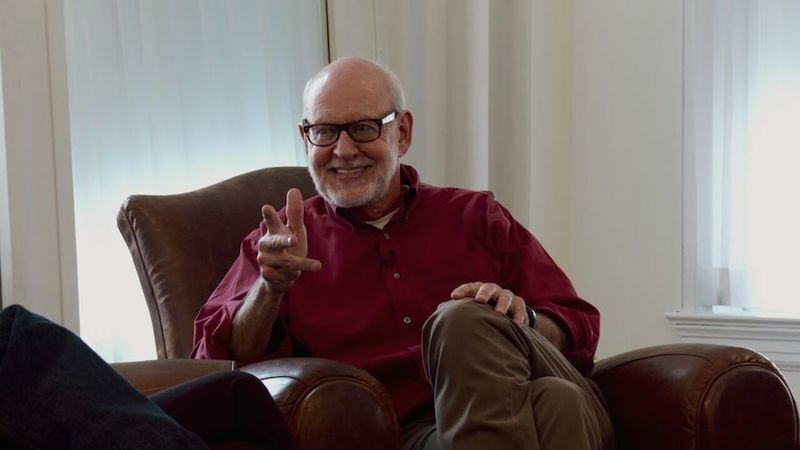

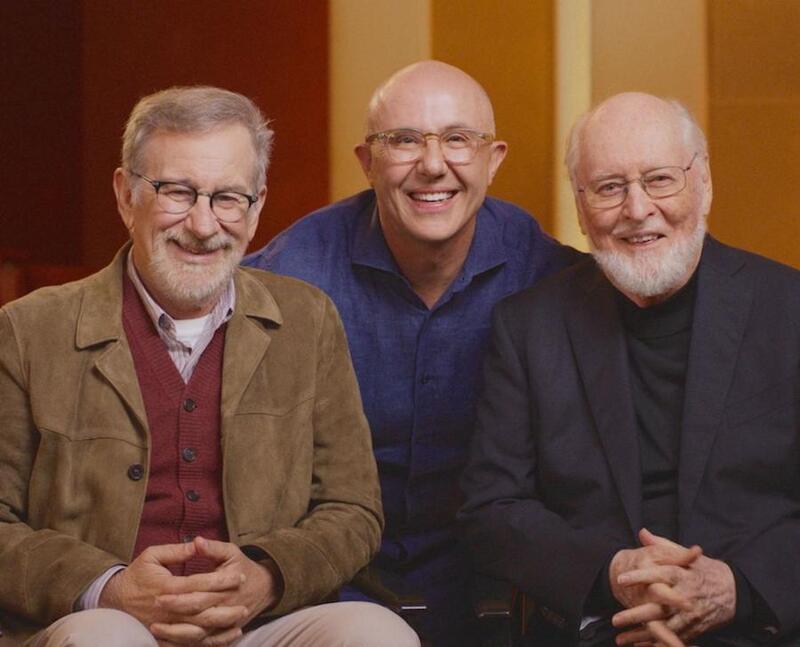

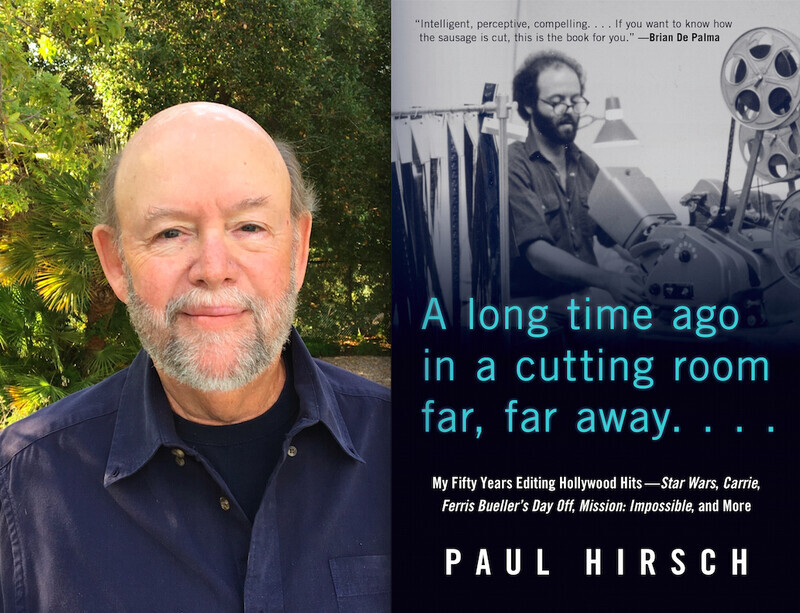

Paul Hirsch on “Planes, Trains and Automobiles”

Del’s one line about his wife turned out to be all the audience needed, and then we cut to Neal bringing him home for Thanksgiving dinner. It was much better for Candy’s character, because he wasn’t throwing himself in front of Steve and begging for kindness. He maintained his dignity. And it was better for Steve’s character because he had enough empathy to figure out what was going on and put it together on his own without having to be told. So it was a case of desperation producing inspiration, and that was what came out of it, but it was in no way planned originally.

Everywhere we screened the film, the audiences started crying during the end scene. A lot of the movie is very freewheeling and from the hip, but in the case of this scene, everything had to be precise—the look, the feel, the eyeline, the slow motion were all very conscious decisions. It would be really wonderful if making movies could be like that all the time, where you aim for a particular vision and actually end up with it. It’s so rare.

Julie Andrews on “Julie’s Greenroom”

Long before Henson came along, I had been considering doing children’s programming and thinking about what would grab them. I didn’t think quite as big as Henson did, but I thought that making a Saturday morning special, maybe with my friend Carol Burnett or someone like Lucille Ball would be so interesting. Then, of course, Henson came along and literally beat me to the finish line because he was so prepared and ready. It was wonderful that he just took the ball and ran with it. From then on, it was literally all about him, as it should’ve been. He was an adorable man. I remember him being very tall and looking sort of like if Lincoln had dressed in a western costume of some kind.

Paul wrote in the script that Claudia looks at the camera and smiles at the end. For me, that was the most difficult scene, because how do you go from abject hopelessness to hope? But I really think the underlying theme of Paul’s films, which is so beautiful, is love. There’s the notion that each moment of love provides a possibility of hope. Even in “There Will Be Blood,” after Daniel Plainview has “drank the milkshake,” and says, “I’m finished!”, there’s something so beautiful about him sitting there in the midst of destruction. He realizes that he can’t get more in blood than he is now, and to me, he has a moment of acceptance. Maybe there’s hope for him, now that he’s finally woken up.

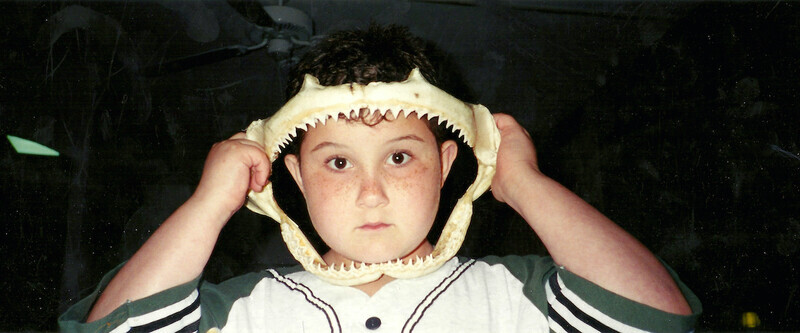

Barry Gifford on “Roy’s World: Barry Gifford’s Chicago”

When it comes to the issue of race, I’m not just looking for a peg to hang my hat on. I am informed on a visceral level. It doesn’t come from nothing and I realize the importance of it, but the key thing as a writer is to make it flow and have it be part of the flow as a natural event. I don’t feel like I have to beat up the reader to get to them. It’s all just part of the structure and story, and that’s what I’m after. That’s what Rob Christopher realized. At the end, he allows me to state the essence of my philosophy and politics, and it’s best encapsulated by Chekhov’s dictum, “I believe in individuals.” That’s my religion.

Rebekah Del Rio on “Mulholland Dr.”

David’s genius is in knowing intuitively, as you said, what will work together, and I feel that the TV shows we watch today are very much influenced by what David did with “Twin Peaks.” David was making cinematic television, and he started that trend. I’m also not just grateful but proud and really honored to have been the Latina in the pivotal moment of such an iconic film. Having me singing with one of the film’s stars, Laura Harring, who is also a Latina, in the audience was this marriage of the demographic that everybody wants to tap into right now. David maybe wasn’t even aware of it, but he was intuitively doing it back in the ’90s. It was ’97 when I went to go sing for him, and it was Brian Loucks who said, “You’ve got to listen to this girl—this is the girl.”

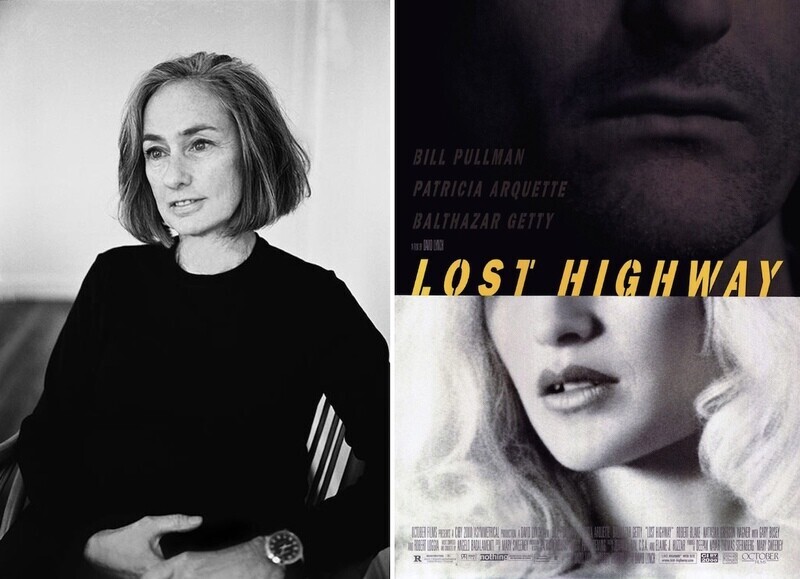

Mary Sweeney on “Lost Highway”

That scene is a perfect example of what occurs when you give an audience a silence. It ends in a wide shot from across the bar on the characters’ backs, and they didn’t let it run long enough. I could’ve easily stayed on that shot for another five or ten seconds. That is such a moving scene, and when you do something abstract or withhold certain information—in this case, keeping the camera on the actors’ backs and not showing their faces, thereby letting the audience sit like these two guys are sitting and contemplating—you will, as a spectator, fill in what the meaning of that is from your own emotional landscape. Those are the films that you can’t stop thinking about in the morning.

Lily McInerny on “Palm Trees and Power Lines”

The truth is, this is why I do it. I feel like it is an enormous privilege to be able to represent these stories. To compromise my comfort for a moment in time for the sake of storytelling is nothing at all like the lived experience of people actually going through these situations. I think actors are incredible, but I don’t think of it as anything as remarkable as surviving in real life.

Abby Ryder Fortson on “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.”

I would love to do another project like “Margaret,” something that is really meaningful and has a special connection to a lot of people. I’m always interested in stories that are relatable, humanistic and that people can benefit from seeing. That’s what storytelling is all about. It lets people have a little escape or reassures them that they’re not alone or provides them with a little fun at the theater or at home after they’ve had a bad day. I really want to do more projects like that. I would also love to try out directing or writing. I’m writing a bit myself, and there are lots of books that I would love to adapt as well as other projects that I would love to be involved in as well.

III. FEATURES

In late 2004, Altman directed a stage adaptation of his 1978 film, “A Wedding,” at Chicago’s Lyric Opera. Ebert recalls this in his Great Movies article: “[Altman] knew his time was limited. ‘Where the years have gone, I don’t know,’ he told me backstage that day at the Lyric. ‘But they’re gone. I used to look for a decade. Now I look for a couple more years.’ He got them.” So did Ebert. The final act of his extraordinary life was an inspiration to all who witnessed it. His refusal to be lionized as an airbrushed icon was the reason why his readers grew so close to him. He hated phoniness as much as Altman did, and allowed people to see the reality of his illness because he wanted to universalize it, removing its societally imposed stigma. That’s what Ebert believed great art could do, and that’s precisely what Steve James’ documentary does so indelibly.

All Are Welcome: Religion at the Movies

Shunning all that is deemed satanic while interpreting illness as a punishment from God, Maria takes it upon herself to “heal” her mute brother. When the girl tries opening up about the minefield of fear and guilt set by her mother (Franziska Weisz) at home, the pastor reminds her of the commandment ordering her to honor her parents. A particularly heartbreaking subplot involves a boy at school who could prove to be a good influence on her, had she not rejected him along with the transcendent beauty of her surroundings. The film warrants comparison with “Breaking the Waves” and “The White Ribbon” in its depiction of how fundamentalism, when taken to its fanatical extremes, is ultimately an embracement of death fueled by the denial of life’s complexities. None of the characters are demonized, not even the mother, who is every bit as tragic a figure.

A Trip Through Film History with Norman Lloyd

As the hospital administrator, Auschlander’s agnostic intellectualism could have merely come off as stuffy, but Lloyd brought an energetic life to the character that made him irresistible. He even got to display his comedic chops in an especially wonderful episode where Auschlander experiments with medical marijuana and ends up causing a scene in a convenience store, exclaiming to a befuddled police officer, “Wait till you get a taste of this beef jerky!” Yet it’s his first scene on “St. Elsewhere” that is surely the most prophetic. A group of doctors (including a young Denzel Washington) are surprised to see Auschlander, who was recently diagnosed with cancer, climbing the stairs to “keep in shape” rather than taking the elevator. Dr. Westphall (the late Ed Flanders) looks at his colleague wistfully before replying, “Knowing him, he’ll probably outlive us all.”

A Special Case of Everyday Life: Philip Glass Attends “Mishima” Screening at University of Chicago

The term “powaqqatsi” means “life in transition,” and that is precisely what is occurring to Truman’s perspective in this scene, as it shifts from a sense of relative comfort to extreme paranoia. Glass’s celebrated use of “repeated motifs woven into ever-changing textures,” as defined by University of Chicago professor Berthold Hoeckner, mirrors the circular trajectory of Truman’s life, which has been trapped within a revolving door of ideological conformity. There’s also an industrial timbre to the music, originally meant to echo Reggio’s footage of the technological growth in developing nations, that here suggests the presence of a great machine designed to hit its precise marks, while blocking Truman’s path toward enlightenment.

Inclusion Rider: Backstage at the 90th Academy Awards

One of the benefits of being in the press room at the Oscars is that you get the chance to hear each of the winners discuss with more depth and detail the issues raised during their speeches, and McDormand’s favored term of “inclusion rider” was one of them. “I just found out about this last week,” McDormand said backstage. “For anybody that does a negotiation on a film, there is an inclusion rider, which means you can ask for and/or demand at least fifty percent diversity, not only in the casting but also the crew, and so the fact that I just learned that after 35 years of being in the film business—we’re not going back.” She shot down the notion that women and African-Americans are merely “trending” in the industry, and felt that “Moonlight” winning Best Picture the previous year was the first sign that change was on the imminent horizon.

RIFF 2018: Iceland, “Donbass” and Swimming with “The Fifth Element”

Many Icelandic locations were utilized for “The Fifth Element,” including the country’s largest ice cap, Vatnajökull, another potential reason why the film was selected for this year’s installment of the festival’s annual Swim-in-Cinema event. Besson would’ve undoubtedly been pleased with the screening, especially since he had originally intended on being a marine biologist (both of his parents were scuba diving instructors). Among the benefits of watching movies in a location this freeing is it gives audiences the opportunity to react not just with their guffaws and clapping hands, but with their entire bodies. Bad films will cause participants to amble distractedly around the water within minutes, so it’s a testament to “The Fifth Element”’s ageless appeal that for the entirety of its two-hour-plus running time, it left the crowded pool of moviegoers transfixed with delight.

Born This Way: Why 1954’s “A Star is Born” is Still the Best

Cukor’s version of “A Star is Born” still proves impossible to equal primarily because of Garland herself, whose performance is one of the greatest ever committed to celluloid. Whereas the 1976 and 2018 remakes culminate in a cathartic musical number, this film offers no such release, making the sense of loss all the more palpable. Aside from her refrain of “It’s a New World,” sung off-camera, Vicki Lester’s last song in the film takes place at the top of the final act: Harold Arlen and Ira Gershwin’s “Lose That Long Face.” It’s an exuberantly high-spirited number, with Garland performing in a hairdo resembling that of her daughter, Liza Minnelli, in later years. When the director yells cut, Lester retreats to her makeup trailer and delivers a searing monologue unmatched by any sequence in every other iteration of the story.

Netflix’s “The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance” Ranks Among the All-Time Great Fantasy Epics

The ending of Kermit and the gang’s first big screen vehicle, James Frawley’s 1979 euphoric landmark, “The Muppet Movie,” is no less profound or open to interpretation as the end of Henson’s “Dark Crystal.” For me, both sequences stand as enduring symbols of diverse beings sharing in the realization of their oneness, as illuminated by a beacon of clarity, whether it be a rainbow or the radiance of three suns. The eye, which Brian Froud considers the focal point of any character, emerges as a crucial motif in Henson’s film, culminating with Thra’s suns aligned to resemble Aughra’s own optical (and detachable) organ, as it peers down into the Crystal of Truth, bringing to light the very essence that binds all living creatures, while affirming that good and evil are two sides of the same coin.

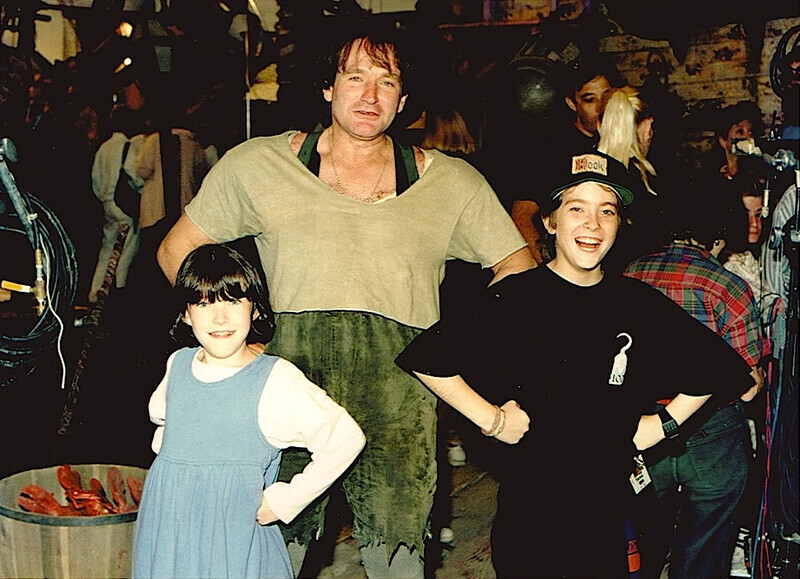

Defying Gravity: Dante Basco, Caroline Goodall, James V. Hart, Charlie Korsmo and More on the Thirtieth Anniversary of “Hook”

It was only recently that I realized Malet had played the son of Mr. Dawes (Dick Van Dyke) in “Mary Poppins,” who cries, “Father, come down!”, as his dad flies into the air when overtaken by a bout of laughter. Tootles does the same thing when Peter surprises him with his lost bag of marbles at the end of “Hook,” thus creating an homage that ingeniously connects the similar character arcs of George Banks—the stuffy father in “Poppins”—and Peter Banning. Neither James nor Jake were aware of this connection when I mentioned it to them (“I cannot tell you how happy I am to know that this is the reality we live in,” Jake gushed upon hearing it), while Goodall agrees that this could not have been a coincidence.

The Perfection of the Human Soul: The Cast of “Groundhog Day” Celebrates Harold Ramis

Like “A Christmas Carol” or “It’s a Wonderful Life,” “Groundhog Day” is a film we annually return to in order to reaffirm our purpose in life. I suppose it was inevitable that Rebecca, the woman I fell in love with, also turned out to be an avid fan of the film. In December of 2020, I proposed to her in the gazebo on the Woodstock Square where Bill Murray danced with Andie MacDowell, who plays Rita, the producer whom Phil desires to one day be worthy of, thus initially triggering his journey toward self-improvement. Rebecca and I were married in Woodstock in July of 2022, and spent our wedding night at the Cherry Tree Inn, where Phil slept. A disc of “Groundhog Day” is preemptively placed in each of the room’s DVD players, and I decided to have its final scene cued up so that I could surprise Rebecca with it when we awoke the following morning. “Do you know what today is?” Phil exclaims to Rita. “No what?” she asks, to which he replies, “Today is tomorrow. It happened.”

To find all of Matt Fagerholm’s work published at RogerEbert.com, click here.